Atlantis Beneath the Ice (15 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

And like the first land of Japanese mythology, Antarctica is close to one of the earth’s poles.

Even if Plato had never recorded the legend of Atlantis, the ancient stories told by people scattered around the globe direct us to the island continent of Antarctica. This last-explored continent may well have been the lost island paradise of world mythology.

SEVEN

ATLANTEAN MAPS

In the winter of 332–331 BCE, Alexander the Great, then only twentyfour, led an army of thirty-five thousand through the unrelenting heat of the Sinai Desert. For seven days the procession marched on barren rock. The sound of tramping boots, the clamor of armor, and the snorting of sweat-stained horses were muffled by the vast emptiness and unforgiving heat. Finally, Alexander led his men out of the desert and into the oasis that was Egypt. He had come to conquer this land as he had so many others.

Egypt’s ruler, having no troops to oppose him, quickly surrendered.

While his men wallowed in wine and soothed their limbs in Egyptian baths, Alexander pondered his future. His old tutor, Aristotle, had impressed on him the wealth of treasures and untold secrets that could be found in the land of the pyramids. His strategic sense told him that Egypt, with desert lying to the west, south, and east, could be an easily defended haven, given adequate equipment and troops. It was settled. He would establish a great city in Egypt to become the western capital of his new empire. It would be called Alexandria.

Alexander eventually left Egypt to pursue and vanquish the Persian armies before marching across even more distant lands. Finally, on the Beas River in present-day India, his exhausted army refused to press onward. They had conquered the known world for their leader. They had had enough. Alexander led them back to Babylon, his eastern capital. There, before his thirty-third birthday, he died, leaving an empire

that stretched a distance equal to the breadth of the United States.

Ptolemy, Alexander’s childhood friend, returned his body to Egypt. There, Ptolemy established a Greek dynasty that would not end until fourteen kings had ruled and the final queen, Cleopatra, had committed suicide as the Romans seized her domain. Ptolemy wouldn’t rest until he had built a great library and museum fit to store all the secrets and treasures of the lands Alexander had conquered. To this end a great effort was made to bring all knowledge together in one place: Alexandria. Preparations for this ambitious task were not made lightly. A hunt through the ancient lands of the Near East was begun, a hunt for long-hidden tablets, mysterious and intriguing maps, the secrets of ancient science, and artifacts to be carried to the museum.

For centuries Alexandria’s library was the world’s center of learning, sought out by all those who wished to follow the maze of their intellect and curiosity. Drawn like iron to magnets, scholars descended on Alexandria to study the secrets of long-lost civilizations.

One of the earliest librarians, Eratosthenes (ca. 275–195 BCE), must have browsed through some incredible works. The secrets of geography, ancient maps, and accounts of daring travel were all closely guarded within the library’s walls. Eratosthenes’ great interest in geography took him to the ancient city of Syene on the Nile. While there, he calculated, within a relatively small degree of error, the true circumference of the earth. This feat he accomplished two and one-half centuries before the birth of Christ.

Euclid (ca. 300 BCE), whose name has become synonymous with geometry, studied at the marvelous library. Archimedes (287–212 BCE) the Thomas Edison of the ancient world, spent day after day cloistered inside, unraveling the secrets of the ancient scrolls of Egypt. After his death, any great inventor was dubbed the new Archimedes. But this gifted man was not infallible. He denigrated one of humankind’s most significant discoveries.

The fact that the earth revolves around the sun is common knowledge in our age, but in ancient Alexandria this idea was considered

ridiculous. Archimedes dismissed with contempt the heliocentric theory of Aristarchos of Samos. Aristarchos (ca. 270 BCE) had come to Alexandria to mine the treasures of the renowned library. He developed the revolutionary idea that the earth was in motion around the sun, an idea that was not accepted for another nineteen hundred years. Perhaps Aristarchos found his inspiration in the pages of the texts of Atlantean sciences that might have lined the shelves of the library.

A series of devastating invasions and fires culminating in the Muslim conquest of 643 BCE during which Caliph Omar decreed that all materials that did not agree with the Koran be burned led to the destruction of this great library. Fortunately many scholars had made copies of important maps, taking them to the safety of the library in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. The surviving ancient maps were of little interest to the Byzantines because they already had lucrative trade routes in place. The science of cartography declined. The maps would lie for centuries gathering dust until an unexpected threat arose from the north.

VIKINGS AND VARANGIANS

The sound of oars slicing through the waters of the misty fjords of northern Europe was heard more and more frequently during the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries. The Scandinavians, feeling the tensions of too many people in too little space, launched an invasion that would sweep through Europe. Dragon-prowed ships with red-bearded men at the helm were spied off the shores of England and France and as far south as Italy. These were the Vikings, and their exploits in the southwest would be matched with excursions to Iceland, Greenland, and North America.

The stories of the Vikings’ daring voyages into the North Atlantic and their ruthless acts of piracy in western Europe have overshadowed an even more amazing chapter in their history. In the early part of the ninth century, the eastern Vikings, who became known

as the Varangians, established a base they called Norovgorod in a city southeast of present-day St. Petersburg. From there they followed the mighty Volga and Dnieper Rivers to the Black Sea and eventually on to Constantinople—jewel of the Byzantine Empire, a city of gold and pageantry, its splendor so renowned that it was known simply as the Big City.

In 860 CE, the Varangians sacked the outer city but failed to penetrate its inner sanctum. After a final attempt at capture failed, an alliance was forged between the Varangians and the Byzantine Empire. By the middle of the tenth century, the Varangians were serving in increasing numbers in Constantinople’s Imperial Navy and became the first adventurers to set eyes on the ancient maps that were once housed in Alexandria’s library.

It was perhaps inevitable that copies of the maps would have found their way back to the Scandinavian homeland. The western Vikings turned their fellows’ bounty to great advantage. Simultaneously as the cartographic treasure chest was opened to them, they made their first discovery of land beyond the Atlantic. Eric the Red (ca. 1000 CE), the discoverer of Greenland, and his son Leif, the first European to reach America, led the long line of explorers who understood the true value of the maps of old Constantinople.

LIBRARIES IN ISLAMIC LANDS

Meanwhile, as the West was suffering the blight of the Dark Ages and enduring the pillages of the Vikings, the Islamic world was thriving in a golden age of learning. Much of the success of this brilliant era can be attributed to the Islamic caliph’s vision of an empire stretching from Spain to India.

Abu-l-Abbas Abd-Allah al-Ma’mun was the caliph (ruler) of an empire that stretched west from Baghdad across North Africa into the Iberian Peninsula and east all the way to India. One night the caliph had a dream in which an old man appeared.

It was as though I was in front of him, filled with fear of him. Then I said, “Who are you?” He replied, “I am Aristotle.” Then I was delighted with him and said, “Oh sage, may I ask you a question?” He said, “Ask it.” Then I asked, “What is good?” He replied, “What is good in the mind.” I said again, “Then what next?” He replied, “What is good in the law.” I said, “Then what is next?” He replied, “What is good with the public.” I said, “Then what more?” He answered, “More? There is no more.”

1

A century after the death of Caliph al-Ma’mun, an Islamic writer told of the effects of the dream. “This dream was one of the most definite reasons for the output of books. Between al-Ma’mun and the Byzantine emperor there was correspondence, for al-Ma’mun had sought aid opposing him. Then he wrote to the Byzantine emperor asking his permission to obtain a selection of old scientific [manuscripts], stored in the Byzantine country.”

2

In 833, on al-Ma’mun’s orders, a library known as the House of Wisdom was established. It was located in Baghdad and became for the Arabs what Alexandria had been for the ancient Greeks. The teachings of the Greeks were revived, and scholars not only copied works but also introduced advancements in mathematics and developed the forerunner of chemistry: alchemy.

Many centuries later, in 1559, an Arabic map of the earth was published. Its source is unknown, but it was translated into Turkish by the Muslim cartographer, Hadji Ahmed. The Hadji Ahmed world map outlines the continent of North America in full, including areas that would not be mapped by Europeans until two centuries later.

3

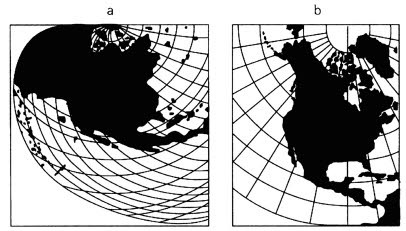

This depiction is remarkable because the technology to measure a continent the size of North America requires an accurate determination of latitude and longitude (see

figure 7.1

).

Prince Henry of Portugal (1394–1460), one of the great minds of the fifteenth century, is often credited with perfecting the determination of latitude—how far north or south of the equator any given place is located. His cartographers knew that the height of the North Star above the horizon gives a close approximation of latitude. If the North Star is at a 50° altitude from the horizon, then the observer is near the 50° latitude. In the Southern Hemisphere, where there is no “South Star” by which to measure, the ship’s captain would “shoot the sun” at noon each day to check for latitude. Astronomy provided the answer to determining latitude.

Figure 7.1.

Found in 1559, the Hadji Ahmed world map depicted a remarkably accurate North America, long before it was explored by Europeans. It may have been drawn by Atlanteans.

The determination of longitude (how far east or west of the Prime Meridian, at Greenwich, England, which is set at 0°) was a much more complicated affair.

The earth is a sphere divided into 360°. Because it takes twentyfour hours to complete one revolution, one hour’s “movement” of the sun equals 15° (360 divided by 24). For example, when it is high noon at Giza, then 15° east of Giza it is 1:00 p.m., and 15° west of Giza it is 11 a.m. This means that to determine when it is noon where we are standing, we must compare that location’s time difference to Greenwich time.

Today radio and satellites allow immediate communication with

any place on Earth. But in the seventeenth century, if you were sailing the high seas, it wasn’t possible to know the time at your home port. This had serious ramifications in 1691 when seven British warships, lost because they couldn’t measure their longitude, were shipwrecked off Plymouth. Then in 1694, a British fleet ran aground on Gibraltar for the same reason, and in 1707, two hundred lives and four ships were lost off the Scilly Isles because the British Navy had no way of determining longitude.

In 1714, the British Parliament set up the British Board of Longitude, which offered “a Publick Reward for such a Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea.” The prize was ten thousand pounds for the invention of a device that could determine a ship’s longitude within one degree of an arc. It was upped to twenty thousand pounds if accuracy could be determined within half a degree. Twenty thousand pounds was a huge incentive in 1714, even for such a daunting task. In today’s currency it would be equal to nearly two million dollars.

In 1735, John Harrison (1693–1776) designed the first marine chronometer, a highly accurate clock tested on a voyage to Lisbon and found to be accurate. Harrison’s fourth, improved marine chronometer underwent its ultimate test on a trip to Jamaica in 1762 and passed easily. But the Board of Longitude, in the tradition of all self-respecting bureaucracies, ensured the perpetuation of its own existence by refusing to grant the money to Harrison. He was given a partial payment of five thousand pounds in 1763, but not until King George III intervened on his behalf did the clever inventor receive the bulk of his reward in 1773. He was eighty years old.