Atlantis Beneath the Ice (19 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

Plato’s vision is also remarkable for the fact that it presents a physical rather than a mythological cause of agriculture. Before his time, all explanations relied upon the intervention of gods and goddesses to

account for the beginning of agriculture. In contrast to these mythological origins of agriculture, Plato presents a very different picture. In his view, agriculture

re-emerges

after the destruction of a great and advanced civilization by earthquakes and floods of extraordinary violence. There are no gods or goddesses to suddenly intervene in the affairs of humankind. Instead, Plato sees the emergence of agriculture as a long, slow battle to recover the foundations of a lost civilization. His is a vision of human beings struggling against the vastly transformed physical conditions brought in the wake of the Great Flood.

We’ve traveled eons in our methods of farming since those first desperate days. In the process we have become dependant on a few key crops and domesticated animals. In North America, the great “breadbasket of the world,” only a small fraction of the population toils to harvest the crops. The efforts of these few, with their highly specialized equipment, have transformed the landscape. To create ever more fertile plants, we intervene in the reproductive process of many crops such as wheat, rice, and corn—crops that would soon be swallowed by wild grasses if left to fend for themselves.

Mile after mile of domestic grains, bent to humankind’s design, have replaced prairie grasses. From the transformed American prairie to the African savanna and Brazilian jungle, wild vegetation has submitted to the demands of the plow. Squeezed by overpopulation, we continuously strip away the natural garment of the earth and cover it with a cloth of our own weave. Our reliance on agriculture is complete. We can’t turn back.

The search to explain the profound mystery of the sudden rise of agriculture on different continents following the climatic changes of 9600 BCE has been one of archaeology’s most persistent quests.

THE MODERN SEARCH FOR AGRICULTURAL ORIGINS

In 1886, Alphonse de Candolle took a botanical approach to the problem of the origins of agriculture. He wrote, “One of the most direct means of

discovering the geographic origin of a cultivated species is to seek in what country it grows spontaneously, and without the help of man.”

3

A dedicated, and ultimately doomed, Soviet botanist, Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov (1887–1943), saw the possibilities in de Candolle’s approach. For two decades, Vavilov patiently gathered a collection of over fifty thousand wild plants. He chose plants that are genetically linked to the domesticated variety we rely on today. Vavilov discovered “eight

independent

centers of origin of the most important cultivated plants.” They were located on the earth’s highest mountain ranges. He wrote, “It is clear that the zone of initial development of the most important cultivated plants lies in the strip between 20° and 45° north latitude, near the high mountain ranges, the Himalayas, the Hindu Kish, those of the Near East, the Balkans, and the Appennines. In the Old World this strip follows the latitudes while in the New World it runs longitudinally. In both cases conforming to the general direction of the great mountain ranges.”

4

Although he was unaware of it, Vavilov’s meticulously measured results support Plato’s claim that mountain elevations were crucial to the reemergence of agriculture (see

figure 8.1

).

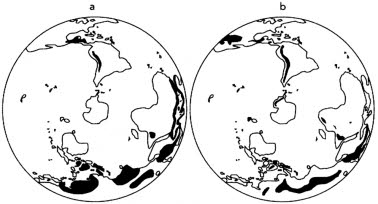

Figure 8.1.

When we place Antarctica at the center of a world map, we can see

(a)

the sites where agriculture originated according to the Russian botanist Nikolai Vavilov. Most domesticated plants were originally domesticated in

(b)

sites at 1,500 meters (4,920 feet) above sea level.

In the cruellest of ironies Nikolai Vavilov was targeted by Josef Stalin as a scapegoat for the horrendous famine that the dictator’s wild policies had inflicted on the Russian people and died of starvation in a prison cell in January 1943.

We aren’t the first world culture to become ensnared in a dependency on sophisticated agricultural techniques. The Atlanteans also were accomplished farmers. They constructed elaborate canals to irrigate immense areas for cultivation. But when the end came, only a few possessed the skill to select the wild plants in the new lands that would sustain them. Those few would be enough.

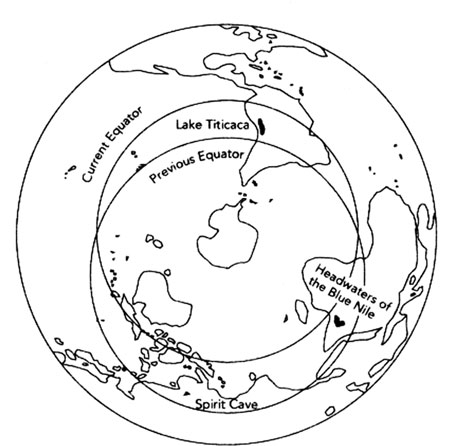

In the tropics, three areas (in South America, Thailand, and Ethiopia) offered climatic stability and security (see

figure 8.2

). All were critical sites in the history of tropical agriculture. In addition, all three:

- Lay midway between the former and current path of the equator

- Received the same amount of annual sunlight both before and after the earth crust displacement

- Were located over 1,500 meters above sea level.

Let’s consider two of these sites. Tropical agriculture suddenly bloomed in South America and Southeast Asia around the same time on exactly opposite sides of the globe. This puzzling phenomenon remains a deep archaeological mystery, but earth crust displacement provides the central missing piece of the puzzle. Rand offered this answer in an article published in the

Anthropological Journal of Canada

(see appendix). His interest lay in the significance of the uncanny locations of agriculture’s earliest sites. This paper was the first to note that potatoes and rice were domesticated in tropical sites that are

antipodal.

a

Of course, the chances of being published in an academic journal if even the whisper of the word

Atlantis

rippled its pages was impossible. Rand made the decision to present only the scientific facts of the research and thereby eliminate the inevitable prejudice against the new ideas. This strategy worked. The article was accepted for publication as the lead article despite the fact that Rand wasn’t an anthropologist. The abstract read,

“A climatic model, based on archaeological evidence is applied to the question of agricultural origins and the sequence of independent civilizations, on a global scale.”

5

Figure 8.2.

Seen from Antarctica, the path of the equator shifted with the last earth crust displacement. Lake Titicaca in the central Andes, Spirit Cave in the highlands of Thailand, and the highlands of Ethiopia were all midway between the current and former path of the equator. These favorable sites were climatically stable and supplied the survivors with raw crops that became potatoes, rice, and millet. The earliest agricultural sites date to 9600 BCE, the same time that Plato says Atlantis perished.

LATIN AMERICA

In Latin America, as we have seen elsewhere around the world, agriculture was established in about 9600 BCE. For instance, in the highlands of ancient Mexico, maize, one of the world’s most important cereals, was suddenly and abruptly domesticated at about that time.

6

Let’ s look at the appearance of agriculture in other places in Latin America. What made them likely sites for this flowering?

Incan mythology weaves a tale about the arrival of godlike men from the

south

who introduced a crop-growing civilization immediately after the Great Flood.

7

As we have seen, it’s probable that these people came from Atlantis, but lets’ examine in more detail how they brought the idea of raising crops rather than hunting for food and the impact of this change.

In 2007, in an area of South America that lies between the current and former locations of the equator, archaeologists unearthed early agricultural remains that included squash, cotton, peanuts, and other “founder crops” such as beans, manioc, chili peppers, and potatoes.

8

Charred remnants of the plants were discovered in houses that date to 11,650 years ago—very close to the date (9600 BCE) that Plato says Atlantis was destroyed and agriculture was rebooted.

One unique plant was also found—quinoa. Designated a “super crop” by the United Nations, quinoa is a remarkably nutritious plant containing a high-protein content. The Inca called it

chisaya mama,

or mother of all grains. Its bitter-tasting shell discourages the attentions of rodents and insects. Someday botanists might be able to reproduce this strategy for protecting crops and free us from our ubiquitous use of chemicals. Each year the Incan emperor used a golden hoe to sow the seeds from this most precious of plants. Archaeologists believe that quinoa was originally domesticated around Lake Titicaca

before

9,200 years ago.

South America was the closest continent to Atlantis. Survivors reached its shores first. Edible crops appeared there shortly after 9600 BCE.

Farming was coaxed to life again near Lake Titicaca, where the amount of annual sunshine remained the same as before the earth crust displacement. Why didn’t the climate change? Prior to the catastrophe Lake Titicaca lay about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) north of the equator. After the crust’s movement, it was dragged 1,000 miles (1,600 km) south of the equator. As a result—even though South America was dramatically impacted by the shifting crust—Lake Titicaca maintained its relative distance

from the equator. This meant that plants and animals from this zone—like potatoes, llamas, and guinea pigs—continued to thrive.

OTHER CLIMATICALLY FAVORABLE SITES

Africa suffered fewer latitude changes than the other continents. In the Ethiopia highlands, around the headwaters of the Blue Nile, the amount of annual sunshine was unaltered after the last earth crust displacement. Because it was roughly the same distance from the equator after the catastrophe as before, it became an oasis of survival. The highlands of Ethiopia may yet yield surprises for archaeologists. Here millet was first domesticated. These highlands would have been an excellent site for the survivors of Atlantis to settle because here, as in Lake Titicaca, the climate was not dramatically changed as a result of the earth crust displacement. Atlanteans may have survived here and eventually followed the Blue Nile down to Egypt to participate in the development of Egyptian civilization.

Rice is one of our most precious crops, providing food daily for almost half the population of the planet. Some of the earliest remains of domesticated rice were found at Spirit Cave

9

in the highlands of Thailand, on the opposite side of the earth—the antipode—from Lake Titicaca. Besides Thailand, early centers of rice cultivation have been found in the Himalayas, eastern India, and southern China.

10

Strangely, it is as if people in all these regions of Asia simultaneously recognized the value of this crop.

After the catastrophe, Egypt shared a common fate with Crete, Sumer, India, and China. This great crescent of land, extending from Egypt to Japan, adjoined an area to the north that remained temperate both before and after the displacement (see

figure 8.3

on page 132). “The abrupt and dramatic changes in climate during the Holocene caused human migrations in many areas.”

11

Can it be mere coincidence—blind chance—that the first five great civilizations all shared a common climatic fate?

The veil obscuring this mystery slips away if we allow that survivors of Atlantis, carrying the knowledge of agriculture and their ancient skills with them, arrived from their destroyed homeland and reinvented agriculture in these viable zones.

Figure 8.3.

A vast crescent of land extending from Egypt to Japan was tropical before the earth crust displacement and temperate afterward. This favored crescent was the birthplace of the world’s first known civilizations.