Atlantis Beneath the Ice (21 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

After the Cold War ended, more Russian scientists joined the international research community. They brought with them the startling finding that American ice-core dating conclusions about Siberia did not match their own evidence. European scientists are also challenging current assumptions about the past climate of the far north.

In 1993, at a site 250 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, Norwegian zoologists Rolv Lie and Stein-Erik Lauritzen discovered polar bear bones dating to the last ice age. The find was surprising because geologists assume that arctic Norway was under a vast ice cap between eighty thousand and ten thousand years ago. No life could survive such a barren environment. The bones were not supposed to be there! Carbon-14 and uranium dating confirmed that the remains must be at least forty-two thousand years old. Further excavations revealed the remains of wolves, field mice, ants, and tree pollen. “The wolf needs large prey like reindeer,” said Lie. “Reindeer in turn, must be able to graze on bare ground. The summers must have been relatively warm and the winters not excessively cold . . . the area wasn’t under an icecap as we believed.”

2

The existence of these animals and the plants that they needed to live challenges common notions about the last ice age. How could an area that was supposedly frozen in the polar zone exhibit characteristics only found in much warmer climates? These difficulties disappear if we surrender the presupposition of a stable earth’s crust and recognize that it is subject to abrupt movement. Then it is possible to see that reindeer, wolves, and ants once thrived in an area that today cannot sustain them.

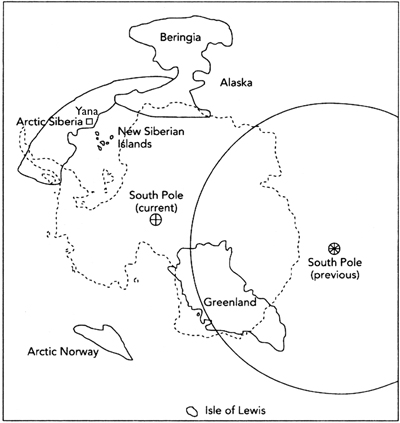

If we peer through a glass globe and align the North Pole with the South Pole, we can see those parts of Antarctica that are antipodes to lands in the north (see

figure 9.4

). This juxtaposition reveals the possibility that Lesser Antarctica once enjoyed a temperate climate capable of supporting Atlantis, similar to the past climate shown by the Norwegian evidence.

The Norwegian discovery was not the only evidence that would challenge our ideas about the Arctic climate before 9600 BCE. Off the northwestern coast of Scotland lies the remote Isle of Lewis. In 1984, two scientists made the unexpected discovery that it was unglaciated between thirty-seven and twenty-three thousand years ago. They wrote, “Models of the last ice sheet showing Scottish ice extending to the continental shelf edge depict the north of Lewis as being covered by 1,000–1,500 metres of ice, but our evidence demonstrates that part of this area was actually ice-free.”

3

When we shift our gaze to arctic America, the evidence continues to build toward a new understanding of the world before 9600 BCE. In 1982, Dr. R. Dale Guthrie, at the Institute of Arctic Biology, was struck by the variety of animals that thrived in Alaska before 9600 BCE. He wrote, “When learning of this exotic mixture of hyenas, mammoths, sabre-toothed cats, camels, horses, rhinos, asses, deer with gigantic antlers, lions, ferrets, saiga, and other Pleistocene species, one cannot help wondering about the world in which they lived. This great diversity of species, so different from that encountered today, raises the most obvious question: is it not likely that the rest of the environment was also different?”

4

Figure 9.4.

A glass globe allows us to see those areas of Antarctica that are antipodal to areas of Alaska, Beringia, northern Siberia, arctic Norway, and Scotland’s Isle of Lewis. Since established scientific evidence of temperate zone conditions has been found in the northern areas, it stands to reason that large parts of Antarctica must have enjoyed temperate conditions prior to 9600 BCE as well.

In 2004, nine Russian scientists reported a remarkable discovery at Yana in northern Siberia. Located at nearly 71° North, the site lies well within the Arctic Circle. Thirty-three thousand years ago humans cohabited in Yana with a host of animals that could not possibly survive in the harsh climate that dominates now. These include “mammoths, rhinoceros, Pleistocene bison, horse, reindeer, musk-ox, wolf, polar fox, Pleistocene lion, brown bear, and wolverine.”

5

The authors of the report, most of whom are with the Russian Academy of Science, noted that “only the reindeer and wolf still inhabit this area.”

When we compare Yana’s current latitude (71° N) to where it would have been

before

the last earth crust displacement, we find that during the time period when the current North Pole was at Hudson Bay, the latitude for Yana would have been 43° N—well outside the polar zone. Notable cities at 43° N today include Vladivostok; Marseilles; Madison, Wisconsin; and Concord, New Hampshire. The animals that lived in Yana thirty-three thousand years ago could survive in the climatic conditions of any of these modern cities.

The significance of the Yana site was not lost on two physicists. Professor Emeritus W. Woelfli of the Institute for Particle Physics in Zürich and Professor W. Baltensperger of the Brazilian Center for Physics Research in Rio de Janeiro both cite the Yana evidence in support of the idea of a radical shift of the earth’s axis around 11,500 years

ago. They repeatedly make the point that Arctic East Siberia must have had a lower latitude in the Pleistocene

6

and mention Hapgood’s work.

These scientists understood that Siberia must have been located at a radically warmer latitude before 9600 BCE. Our fixation with the belief that the earth’s crust has always been stable in relation to its axis blinds us to the legacy left in ancient Alaska and the traces of the past to be found in Siberia’s flora and fauna. The evidence collected from Yana proclaims that

temperate,

not polar, conditions must have prevailed in Siberia.

OSSIP’S DISCOVERY

In the summer of 1799, while searching for ivory in the isolated wilderness of Siberia, a Tungus chief named Ossip Shumakhov encountered, complete with preserved hair and flesh, the ice-encapsulated carcass of a mammoth. The chief was terrified. Legend foretold that any whose gaze fell on one of these creatures would soon die. As predicted, within a few days Shumakhov grew ill. However, to his own and everyone else’s surprise, he made a complete recovery.

With renewed courage, Shumakhov set out to revisit the frozen mammoth, this time taking along several curious Russian scientists. Excited to discover that Shumakhov’s fantastic account was true, they shipped the remains of the incredible creature to St. Petersburg, where it can still be seen today.

On the heels of this sensational discovery, the New Siberian Islands, in the Arctic Ocean, gave up the desolate graves of thousands of large animals. The find created confusion among scientists. How could these huge creatures, requiring vast amounts of vegetation to fuel their daily existence, thrive in such large herds on barren dunes of ice? And what incredible force had destroyed them?

One of the first and most distinguished scholars to accept the challenge of these questions was Georges Cuvier (1769–1832) a French naturalist. Cuvier had already created a sensation by unearthing and

reassembling a prehistoric elephant from the ground beneath Paris. This was only one of the amazing discoveries that the inquisitive Cuvier would reveal to a startled Europe. By his midthirties he had become the dominant scientific thinker of his era, clearing new paths in virtually all of the natural sciences.

Cuvier’s flamboyant character, combined with his colorful discoveries, made him a favorite object of gossip in the fashionable salons. It was said that late one night Cuvier’s students decided to play a practical joke on him. One of them, dressed in a red cape to represent the devil, artificial horns secured to his head and hooves tied to his feet, burst into the sleeping professor’s chambers shouting that he had come to devour the learned scientist! Cuvier awoke, calmly examined the spectacle before him and pronounced, “You have horns and hooves; you can only eat plants.”

Cuvier labored long hours over the mystery of the ancient bones from Siberia and the inevitable questions they raised. He became more and more convinced that the world had experienced a catastrophe of unspeakable dimensions and that man “might have inhabited certain circumscribed regions, whence he repeopled the earth after these terrible events; perhaps even the places he inhabited were entirely swallowed up and his bones buried in the depths of the present seas, except for a small number of individuals who carried on the race.”

7

The unexpected discovery of frozen giants in the wastelands of Siberia excited Cuvier’s genius and proved to him that the earth had suffered sudden, destructive convulsions and upheavals.

These repeated eruptions and retreats of the sea have neither been slow nor gradual; most of the catastrophes that have occasioned them have been sudden; and this is easily proved, especially with regard to the last of them, the traces of which are most conspicuous. In the northern regions it has left the carcasses of some large quadrupeds, which the ice had arrested, and which are preserved even to the present day with their skin, their hair, and their flesh. If they

had not been frozen as soon as killed they must quickly have been decomposed by putrefaction. But this eternal frost could not have taken possession of the regions that these animals inhabited except by the same cause, which destroyed them; this cause, therefore, must have been as sudden as its effect. The breaking to pieces and overturning of the strata, which happened in former catastrophes, shew [

sic

] plainly enough that they were sudden and violent like the last; and the heaps of debris and rounded pebbles which are found in various places among the solid strata, demonstrate the vast force of the motions excited in the mass of waters by these overturnings. Life, therefore, has been often disturbed on this earth by terrible events—calamities which, at their commencement, have perhaps moved and overturned to a great depth the entire outer crust of the globe, but which, since these first commotions, have uniformly acted at a less depth and less generally.

8

At the time Cuvier put forward his theory, geologists were involved in an intense debate with the church over the role of catastrophes in the earth’s history. Although he was greatly respected, Cuvier’s theory of an earth crust displacement was unacceptable to the scientific establishment. It was associated with the idea of a supernatural force (God) that could overturn the laws of nature at will. It was also unacceptable to the religious fanatics, who, although they liked Cuvier’s earthquakes and floods, didn’t accept his timing, which placed these events far earlier than the Bible proclaimed. And so Cuvier’s theory that mass extinctions were caused by displacements of the earth’s crust was suffocated in the heated debate between religious extremists and defensive scientists.

However, one man who based his studies on Cuvier’s theory developed what is still an accepted concept: the idea of the ice ages. Naturalist and geologist Louis Agassiz (1807–1873) was born in Motier, Switzerland. From an early age Agassiz was blessed with the ambition and determination to make his unique mark on the history of science.

Only twenty-two when his first work,

Brazilian Fish,

was published, he dedicated the book to Cuvier, “whom I revere as a father, and whose works have been till now my only guide.” Cuvier responded to the young scientist with a complimentary letter suggesting additional lines of investigation.

With this encouragement, Agassiz continued to study the evolution of fish while maintaining the medical career urged on him by his parents. In October 1831, in what was to be a sadly ironic turn of events, he seized the opportunity to travel to Paris to study a grim cholera epidemic. He wasted no time in presenting himself to Cuvier. The great man was impressed with Agassiz’s work and took a liking to the enthusiastic young Swiss, perhaps seeing reflections of his younger self in the bold-featured youth nervously spreading his research before him.

Cuvier turned over to Agassiz one of his elaborately equipped laboratories and all his personal notes on the subject of their mutual interest. The topic of fish fossils also held a fascination for Cuvier, and realizing that Agassiz had independently arrived at similar conclusions, he was unceasingly generous in his aid, providing advice and encouragement whenever needed, even the occasional meal at his home, where many contemporary original thinkers mingled over wine and cigars.

In May of 1832, tragedy struck. Cuvier was taken by the very cholera Agassiz had originally come to Paris to study. The impact of this painful event on Agassiz was profound. “With Cuvier’s death, whatever sense of intellectual independence Agassiz had known disappeared. The fact that the great naturalist had turned over important fossils to him for description and publication made Agassiz think of himself as Cuvier’s disciple. He determined to mode his intellectual efforts after the pattern set for him by Cuvier.”

9

Agassiz adopted Cuvier’s conclusion that the earth’s history had been periodically marked by great catastrophes that had destroyed existing plants and animals and wiped clean the slate for the creation of new creatures by God. These ideas, known as

catastrophism

and

special creation,

were concepts Agassiz would hold for the rest of his life and

were fundamental to his physical view of the world. The first, catastrophism, was a conclusion based on the fossil record, an interpretation of the known facts. But the second idea, special creation, drifted from the precision of scientific data into the murky arena of theology.