Atlantis Beneath the Ice (20 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

BANANAS AND SUGAR

At Kuk in the central highlands of New Guinea something remarkable happened around the time of the fall of Atlantis. So momentous are these discoveries that the area has been designated a World Heritage Site.

12

New Guinea is the third largest island in the world after Antarctica and Greenland. A mysterious land, Europeans did not penetrate its central highlands until the 1930s and only then using air power. However, New Guinea has been occupied for at least forty thousand years.

13

During the first thirty thousand years the people lived by hunting and gathering. But abruptly, around ten thousand years ago, they suddenly moved into the highlands, taking with them plants that had always been cultivated at sea level. They cleared the land and systematically drained a swamp that eventually would become the birthplace of several

important domesticated crops, most notably bananas and sugar cane.

Why would people who had been living as hunters and gatherers for thousands of years suddenly climb high up to the central plateau of New Guinea, drain a swamp, and plant bananas, a crop that can take twenty years to become viable? Why would people who had been perfectly adapted to the land for thirty thousand years suddenly abandon their longestablished and successful means of subsistence and opt for agriculture? And why did they find it necessary to leave the coastal regions at all?

These questions haunted the Australian archaeologist Jack Golson, who has spent a lifetime trying to solve this New Guinea riddle.

14

Golson and his partner on the quest, Phillip Hughes, became convinced of the radical idea that Kuk was deliberately created as a cradle for agriculture. At an early stage they made the remarkable discovery of a “paleochannel,” a sophisticated landscaping device for draining a swamp to create tillable land.

b

Once again, the occurrence of an earth crust displacement makes sense of the sudden appearance of these advanced tools. Kuk lies at an altitude of 1,560 meters, making the temperature there several degrees cooler than in the hot lowlands, where its transplanted wild plants originated. When New Guinea moved some 20° closer to the equator as a result of the earth’s crust shifting around 9600 BCE, the sudden rise in annual temperatures forced the New Guineans to adapt. Their obvious solution was to move to the highlands. For every 150 meters they climbed the temperature dropped by one degree.

c

At 1,500 meters they could reestablish their settlements and enjoy the temperatures that had previously prevailed at sea level.

Is the mystery of Kuk reflecting a distant mirror of a long-lost civilization? Plato tells us that the people of Atlantis were masters at manipulating the flow of water to sustain agriculture. After 9600 BCE, when Atlantis perished, early agricultural experiments sprung up around the globe, followed eventually by vast water engineering projects designed to enhance crop production. In Central and South America, Egypt, Sumer, India, and China all of the early civilizations relied on massive water engineering projects. Is this mere coincidence?

NINE

THE RING OF DEATH

Seen from space, our planet is a tiny turquoise jewel in a midnight black setting. But one landmass stands out from most of the others—the shining snow-covered continent of Antarctica. The continent of Antarctica is immense, covering a greater area than the mainland United States. But it is a mysterious and hostile place where few humans dare to venture. Cold, nightless summers fade into freezing, sunless winters. And always there is the wind, the constant howling wind of a land forgotten. Most of the earth’s precious fresh water is locked within its ice cap. The very existence of this vast ice cap points to a climatic conundrum. At the same time it provides a clue to the great convulsions that have seized the earth in the past.

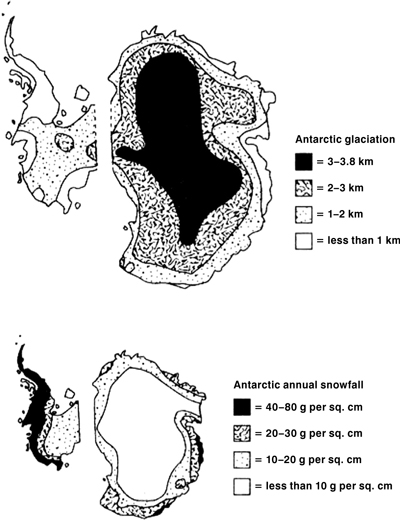

Geographers distinguish between “Lesser Antarctica” and “Greater Antarctica” (see

figure 9.1

on page 136). Lesser Antarctica, the tail of land that points toward South America, is characterized by its mountains, relatively thin ice sheet, and heavy snowfall. The body of the continent, Greater Antarctica, groans beneath a massive weight of ice. The ice is over two miles thick, even though the area receives very little annual snowfall. It is, in fact, a polar desert (see

figure 9.2

on page 136). This puzzling disparity between annual snowfall rates and the great depth of its ice sheet reveals that Antarctica’s climate must have been radically different in the past, that there must have been a time when snowfall was commonplace.

Each spot on the earth’s surface has an “antipodal” point, that is,

a point exactly on the opposite side of the planet. If a line is drawn through one point on the earth, through the exact center of the earth, that line will emerge at its antipodal point. The North Pole is antipodal to the South Pole. England and New Zealand are antipodal. North America and the southern part of the Indian Ocean lie on the opposite sides of the earth. Greenland, covered with the largest ice sheet in the northern hemisphere, is very close to being antipodal to the great ice cap on Greater Antarctica. The area of thickest ice on Greenland overlaps the area of thickest ice on Antarctica. In every case, the points that are antipodal share the same amount of annual sunshine and thus similar temperatures.

Figure 9.1.

The island continent of Antarctica is comparable in size to the lower forty-eight states of the United States. Geographers separate the continent into “Lesser Antarctica” and “Greater Antarctica.”

Figure 9.2.

Today’s climate conditions cannot account for the shape of the ice sheets on Antarctica. Lesser Antarctica has the least ice but the most annual snowfall, while Greater Antarctica holds the most ice yet experiences the least snowfall. Antarctic glaciation data from Strahler,

Introduction to Physical Geography

, 355. Antarctic annual snowfall data from Rubin, “Antarctic Meteorology,” 161.

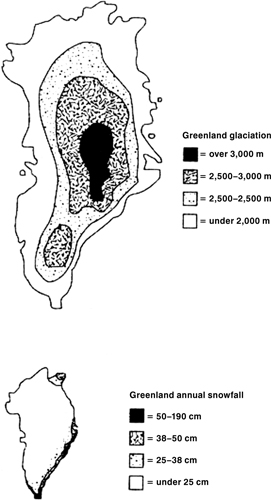

Like its cousin in the south, Greenland’s current snowfall does not match its ice cap. The current climate cannot possibly account for the ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica, and yet there has not been any explanation for this “odd” placement of the ice sheets. The problem is ignored. The present largest ice sheets are antipodal yet lopsided relative to the earth’s axis. This suggests a displacement of the earth’s crust—to be expected when lands shift in and out of the polar regions.

Earth crust displacement does, in fact, provide an answer to the problem. As the earth’s crust shifts, it moves through the climatic zones. Some lands that had enjoyed mild climates before the shift were dragged into the polar zones. As a result, they received more snow. Other lands were released from the polar zones as they were shifted into warmer climates, causing their ice sheets to melt. Greenland and Greater Antarctica were locked into the polar zones before

and

after the displacement. Since these lands experienced polar conditions longer than any other parts of the world, they accumulated the greatest ice sheets. The overlapping old and new Arctic and Antarctica circles (it is actually the crust that moves, not the polar zones) leave the old ice sheets intact.

Until 9600 BC, Lesser Antarctica was outside the polar zone. This area has hardly been explored for two reasons. First, three nations (Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom) all lay claim to it. No

system of law has been established and territorial disputes overlap. Second, most scientists focus on studying Greater Antarctica’s vast ice sheet. Because of limited data about the area of the continent that is most important to the mystery of Atlantis, we must gauge Lesser Antarctica’s past climate using the antipodal argument.

Greenland, smothered by the largest ice sheet in the Northern Hemisphere, lies in an antipodal position to the great ice cap on Greater Antarctica. Its area of thickest ice corresponds to the thick ice on Antarctica (see

figure 9.3

). It is also a polar desert that receives minimal snowfall. Unexpectedly, neither ice sheet is centered at a pole.

Climatologists insist that the colossal size of these antipodal, lop-

sided ice caps couldn’t possibly be realized under current snowfall conditions. They must have been formed by some other phenomenon. This glaring anomaly has

never

been explained by geologists.

a

Figure 9.3.

Greenland’s massive ice cap cannot be explained by the annual snowfall patterns. Greenland glaciation data from Strahler,

Introduction to Physical Geography

, 354. Greenland annual snowfall data from Rumney,

Climatology and the World’s Climate,

116.

Charles Hapgood’s theory of a sliding crust and/or mantle is the tool that can unlock the mystery of aberrant glaciation patterns. As the earth’s crust shifts, it moves through the climatic zones. Land that had previously enjoyed a mild climate is dragged into polar zones, exposing it to more snow. Other areas are released from frigid zones and shift into warmer climes, causing ice sheets to melt.

Central Greenland and Greater Antarctica are the only regions on Earth that remained within polar zones both before and after the last displacement. As a result there has never been an opportunity for their ice to melt. Antipodal, lopsided ice sheets are exactly what we would expect if the earth’s crust is dramatically shifted over a relatively short period of time with no opportunity for the ice-locked land to thaw.

b

ANTARCTICA’S ANTIPODES

Only a few thousand people live on Antarctica at any given time. They are primarily preoccupied with astronomical and climatic studies that rely on ice-core dating, a discipline fraught with difficulties.

1

In contrast, we know a great deal more about the Arctic, where Russian, European, American, and Canadian scientists have studied the climate extensively. The wide range of scientific data gathered from the north has been used to provide models of the climate that ruled the polar south in the past. (Most American scientists approach the problem from the opposite direction. They attempt to explain climatic conditions in places like Siberia and Beringia by using ice core dating from Antarctica.)