Atlantis Beneath the Ice (24 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

After World War II, anthropologists and archaeologists confirmed the discovery of a former land bridge between Siberia and Alaska called Beringia. This land, now lost to the ocean, seemed to vindicate Acosta’s original idea that people came to America by land. After World War II the idea of the land bridge route became the official explanation for the peopling of America and as with all things “official,” it soon became sacrosanct. Any suggestion that people came from anywhere other than Siberia was ignored.

Initially, the land bridge theory did dovetail with the physical evidence unearthed that characterized the first Americans as big game hunters. These supposed “first” Americans used a “clovis” blade (named after an excavation site near Clovis, New Mexico). A paradigm, known as the

clovis first theory,

13

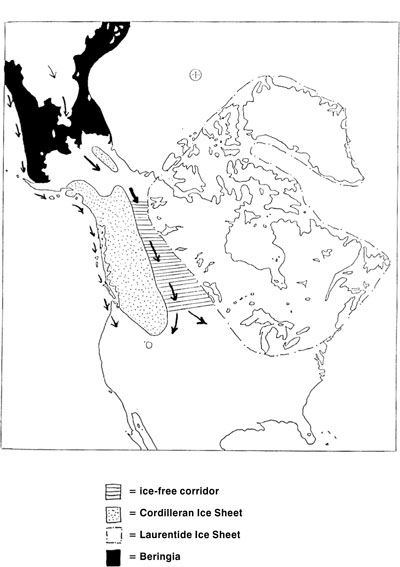

soon gripped the archaeological establishment. It assumed that at approximately 9500 BCE the earliest native people of America arrived as big-game hunters from Asia. They traveled across the Beringia land bridge through an ice-free corridor that passed between the massive ice sheets that otherwise blocked their way (see

figure 10.1

).

Let’s consider these ice sheets and the possible ice-free corridor. At the same time that arctic Siberia was full of life and largely free

of ice, two vast ice sheets bore down on North America. At its height the Laurentide Ice Sheet, centered on Hudson Bay, was larger than Antarctica’s current ice cap. It covered most of Canada as well as the states that border the Great Lakes. In the west, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet lay along the Rocky Mountains, covering southern Alaska, almost all of British Columbia, and a good share of Alberta, Washington State, Idaho, and Montana. The lower ocean level created the Beringia land bridge, which connected an ice-free Alaska with an ice-free Siberia.

Figure 10.1.

The long accepted theory of the peopling of America states that 11,600 years ago an ice-free corridor opened between the western and eastern ice sheets of North America allowing people from Siberia to make their way between the ice sheets to reach the central plains. A more recent theory suggests that people in boats may have followed the Pacific coast to arrive in America.

At that time, an ice-free corridor between the ice sheets was believed by archaeologists to be the sole avenue of entrance to America by people coming from Siberia. While we do not subscribe to this theory, we note that the existence of the ice-free corridor has never been explained. Why should this region be ice-free? Archaeologists and geologists have no idea. Hapgood supplies a simple answer: The crust was in a different position when the corridor was formed. The sun would rise from the direction of the Gulf of Mexico and set toward the Yukon. This arc of sunshine cut a path through the ice and melted the snow that fell there. The appearance of the ice-free corridor is no longer so “odd” (see figures

10.2

–

10.5

).

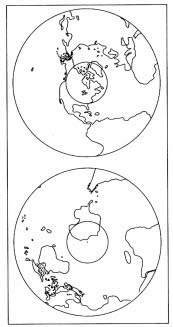

Figure 10.2.

Before 91,600 BCE, the Arctic Circle was centered on the northwest corner of North America. In the Southern Hemisphere, that part of Greater Antarctica that lies toward Africa was under ice. Much of Lesser Antarctica was ice free. The Cordilleran Ice Sheet of northwest North America was created at this time.

Figure 10.3.

After the first displacement, in the years from 91,600 BCE to 50,600, the Arctic Circle contained much of Europe and all of Greenland. Passage from Asia to America was open. Northwestern Siberia, Beringia, and Alaska enjoyed a mild climate. In the Southern Hemisphere, the part of Greater Antarctica leaning toward New Zealand was under ice.

Figure 10.4.

After the second displacement, between 50,600 and 9600 BCE, North America felt the grip of the Arctic Circle. Most of Greenland remained in the polar zone. The massive Laurentide Ice Sheet on North America was created at this time. Lesser Antarctica, the site of Atlantis, along with Siberia, Beringia, and Alaska, was ice-free except at high altitudes. During this time migration from Asia to the New World was open.

Figure 10.5.

After the third earth crust displacement in 9600 BCE, North America was freed from the icy grip of the polar zone, which left the Great Lakes in its wake. Greenland was for the third straight time trapped inside the Arctic Circle (except for the southern tip), accounting for 90 percent of the ice in the Northern Hemisphere. Siberia, for the first time, was brought into the polar zone. All of Antarctica was encapsulated by the Antarctic Circle, causing a “dire winter” on the island continent, as recorded in the Vedic story of the lost island paradise of Airyana Vaêjo.

So after consideration of these earth crust displacements, was there an alternate ice-free corridor into America, rather than a corridor down the center of Canada? Consider this: In the March 1994 issue of

Popular Science,

Ray Nelson reported on an important archaeological find in New Mexico. Dr. Richard S. MacNeish, along with his team from the Andover Foundation for Archaeological Research, excavated a site at Pendejo Cave, in southwestern New Mexico. They found eleven human hairs in a cave about one hundred meters above the desert. Radiocarbon testing dated them at fifty-five thousand years ago.

14

MacNeish’s find is important because it confirms that migration to North America from Siberia was possible between 91,600 BCE and 50,600 BCE (see

figure 10.3

) and again after the next earth crust displacement at 50,600 BCE (see

figure 10.4

). This displacement dragged eastern North America into the polar zone but left islands off the Pacific coast free of ice. The Arctic Circle then lay over Hudson Bay. Greenland remained in the polar zone. Theoretically, from 91,600 BCE

to 9600 BCE, people travelling in boats could have moved from Siberia to America along the Pacific Coast where they could navigate between the ice-free islands (see

figure 10.6

).

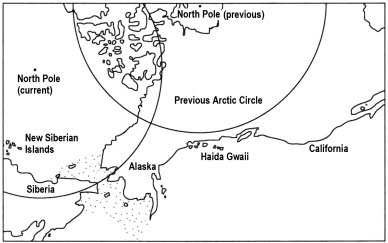

Figure 10.6.

Directions change with each earth crust displacement. Before the last catastrophe, the Pacific side of North America was actually the south, while the Arctic Circle was centered on Hudson Bay. Seen from this perspective, the migration of people from Siberia, across Beringia, and along the Pacific coast would be a movement from west to east. Seen from Haida Gwaii, the sun would appear to rise from the direction of California and set in the direction of Alaska.

This Pacific waterway to America was open and inviting and has, since the publication of the first edition of this book in 1995, become the prevailing theory of how people arrived in America. But these archaeological theories have a serious blind spot. None of them take any account of what the people themselves say.

If we listen with respect to the tales that the people of the First Nations of America tell then we find no stories of ice walls or traveling through ice. Instead, we discover an entirely different scenario from that favored by archaeologists. It is a scenario of violent upheaval from a homeland that was destroyed (see

chapter 5

). There are stories of arrival in ships and others that tell of ancient ancestors who were already in

America and were forced to climb mountains to save themselves from the rising ocean.

In the past decade the clovis first theory of the peopling of America has fallen apart as each of its assumptions was challenged by physical evidence. This evidence has come primarily from South America, which has more “pre-Clovis” sites than North America.

15

The contradictions between the physical evidence in South America and the theories from North America have only recently come to light because a whole new generation of Latin American archaeologists has entered the field.

It was Plato who first commented on the conditions that permit the exploration of the past. “The enquiry into antiquity are first introduced into cities when they begin to have leisure, and when they see that the necessaries of life have already been provided, but not before.”

16

The prosperity of North America gave its theorists an advantage in archaeology for it allowed universities in the United States and Canada to turn out waves of archaeologists whose focus was North America. The far fewer numbers of Latin American archaeologists were at a disadvantage. Theories were developed primarily in the United States and were applied to Central and South America even before excavations had been carried out. Argentine archaeologist Vivian Scheinshon complained in 2003, “South American huntergatherer archaeology has been strongly influence by North American archaeology. Automatic application of North American models in South America and a tendency to overemphasize similitude on both continents were the consequences.”

17