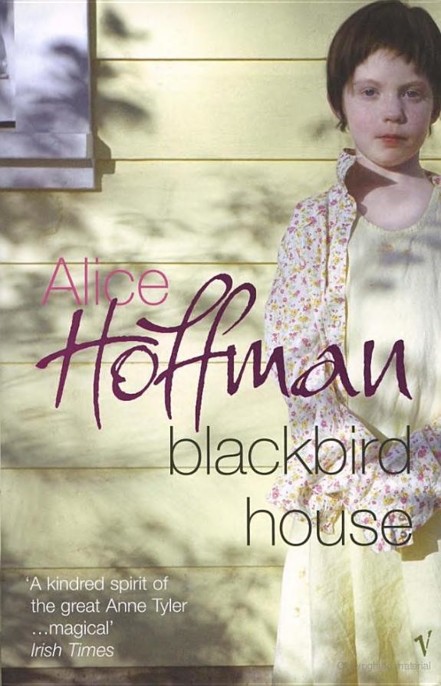

Blackbird House

Authors: Alice Hoffman

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Short Stories (Single Author)

By Alice Hoffman

Synopsis:

From the great May storm in 1778, when John Hadley and his sons slip the British blockade off the coast of

and wild fruit vines and red pear trees, coil I and weave around each other, right up to the present.

Young Isaac Hadley is more interested in his pet blackbird and the star charts in The Practical Navigator than in helping to build the house; and Violet, a century later, with her stained face and her own ghostly bird, reads the same book, and finds that it’s easy enough to trick a learned man, though harder to catch one... Larkin Howard is ready to sell his soul to buy the farm, but meets a woman who hears the whales cry on the beach; while in another century the young Farrell boy sees more than he should on a snowy night... and the pond at the back is still dark and unforgiving beneath its deceptively golden lilies.

By the 1950s, the farmhouse is part of a community of steady men and wayward boys, and women who make jam but still feel the ghostly breath of Cora Hadley, with her green fingers.

As a second century draws to a close and summer visitors from the cities take over the countryside, the house can barely hold all its ghosts, but the tragedies are not over.

Gripping and poignant, a dazzling fictional achievement from a favourite novelist, this is the irresistible story of a house, its inhabitants, its history, and the ghosts that haunt a spit of land.

12.99

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Probable Future

Blue Diary The River King

Local Girls

Here on Earth

Practical Magic

Second Nature

Turtle Moon

Seventh Heaven

At Risk

Illumination Night

Fortune’s Daughter

White Horses

Angel Landing

The Drowning Season

Property Of

FOR CHILDREN Green Angel

Indigo

Aquamarine

Horsefly

Fireflies

Alice Hoffman

BLACKBIRD HOUSE

Chatto & Windus

LONDON

Published by Chatto & Windus 2004 First published in the United States

of America in 2004 by Doubleday

2468 10 97531 Copyright 2004 by Alice Hoffman

Alice Hoffmann has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of

trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated

without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover

other than that in which it is published and without a similar

condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent

purchaser

Excerpts from this work first appeared in the Boston Globe Magazine,

Boulevard Five

Points, Harvard Review,

Schooner and Southwest Review

First published in Great Britain in 2004 by

Chatto & Windus

Random House,

SWlV 2SA

Random House Australia (Pty) Limited

Random House New Zealand Limited

10, New Zealand

Random House (Pty) Limited Endulini, 5A Jubilee Road, park town 2193,

South Africa

The Random House Group Limited Reg.

No.

954009 www.

random

house.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library ISBN o 7011 7513 3

Papers used by Random House are natural,

recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests;

the manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of

the country of origin

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham plc, Chatham,

Kent

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix

THE EDGE OF THE WORLD 1

THE WITCH OF TRURO 23

THE TOKEN 39

INSULTING THE ANGELS 51

BLACK IS THE COLOR OF MY TRUE LOVE’S HAIR 73

LION HEART 93

THE CONJURER’S HANDBOOK 109 THE WEDDING OF SNOW AND ICE 131

INDIA 151

THE PEAR TREE 173

THE SUMMER KITCHEN 187

WISH YOU WERE HERE 205

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank the editors of the magazines in which some of these stories first appeared: the Boston Globe Magazine, Boulevard, Five Points, Harvard Review,

Special gratitude to Richard Bausch for his kindness and generosity.

Thank you to the women willing to run off to sea: Perri Klass, Alexandra Marshall, and especially Jill McCorkle.

Thanks to my first readers: Maggie Stern Terris, Elizabeth Hodges, Carol De Knight Sue Standing, and Tom Martin.

Gratitude to Elaine Markson and to Gary Johnson.

To my sons, thank you for helping me to understand.

And many thanks to Q, who showed me what courage looked like.

BLACKBIRD HOUSE

THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

I.

IT WAS SAID THAT BOYS SHOULD GO ON

their first sea voyage at the age of ten, but surely this notion was never put forth by anyone’s mother.

If the bay were to be raised one degree in temperature for every woman who had lost the man or child she loved at sea, the water would have boiled, throwing off steam even in the dead of winter, poaching the bluefish and herrings as they swam.

Every May, the women in town gathered at the wharf.

No matter how beautiful the day, scented with new grass or spring onions, they found themselves wishing for snow and ice, for gray November, for December’s gales and land-locked harbors, for fleets that returned, safe and sound, all hands accounted for, all boys grown into men.

Women who had never left

The place that could take it all away.

This year the fear of what might be was worse than ever, never mind gales and storms and starvation and accidents, never mind rum and arguments and empty nets.

This year the British had placed an embargo on the ships of the Cape.

No one could go in or out of the harbor, except unlawfully, which is what the fishermen in town planned to do come May, setting off on moonless nights, a few sloops at a time, with the full knowledge that every man caught would be put to death for treason and every boy would be sent to Dartmoor Prison in England as good as death, people in town agreed, but colder and some said more miserable.

Most people made their intentions known right away, those who would go and those who would stay behind to man the fort beside Long Pond if need be, a battle station that was more of a cabin than anything, but at least it was something solid to lean against should a man have to take aim and fire.

John Hadley was among those who wanted to stay He made that clear, and everyone knew he had his reasons.

He had just finished the little house in the hollow that he’d been working on with his older son, Vincent, for nearly three years.

During this time, John Hadley and Vincent had gone out fishing each summer, searching out bluefish and halibut, fish large enough so that you could fill up your catch in a very short time.

John’s sloop was small, his desires were few: he wanted to give his wife this house, nothing fancy, but carefully made all the same, along with the acreage around it, a meadow filled with wild grapes and winterberry.

Wood for building was hard to come by, so John had used old wrecked boats for the joists, deadwood he’d found in the shipyard, and when there was none of that to be had, he used fruit wood he’d culled from his property, though people insisted apple wood and pear wouldn’t last.

There was no glass in the windows, only oiled paper, but the light that came through was dazzling and yellow; little flies buzzed in and out of the light, and everything seemed slow, molasses slow, lovesick slow.

John Hadley felt a deep love for his wife, Coral, more so than anyone might guess.

He was still tongue-tied in her presence, and he had the foolish notion that he could give her something no other man could.

Something precious and lasting and hers alone.

It was the house he had in mind whenever he looked at Coral.

This was what love was to him: when he was at sea he could hardly sleep without the feel of her beside him.

She was his anchor, she was his home; she was the road that led to everything that mattered to John Hadley.

Otis West and his cousin Harris Maguire had helped with the plans for the house a keeping room, an attic for the boys, a separate chamber for John and Coral.

These men were good neighbors, and they’d helped again when the joists were ready, even though they both thought John was a fool for giving up the sea.

A man didn’t give up who he was, just to settle down.

He didn’t trade his freedom for turnips.

Still, these neighbors spent day after day working alongside John and Vincent, bringing their oxen to help lift the crossbeams, hollering for joy when the heart of the work was done, ready to get out the good rum.

The town was like that: for or against you, people helped each other out.

Even old Margaret Swift, who was foolish enough to have raised the British flag on the pole outside her house, was politely served when she came into the livery store, though there were folks in town who believed that by rights she should be drinking tar and spitting feathers.

John’s son Vincent was a big help in the building of the house, just as he was out at sea, and because of this they would soon be able to move out of the rooms they let at Hannah Crosby’s house.

But Isaac, the younger boy, who had just turned ten, was not quite so helpful.

He meant to be, but he was still a child, and he’d recently found a baby blackbird that kept him busy.

Too busy for other chores, it seemed.

First, he’d had to feed the motherless creature every hour with crushed worms and johnnycake crumbs, then he’d had to drip water into the bird’s beak from the tip of his finger.

He’d started to hum to the blackbird, as if it were a real baby.

He’d started to talk to it when he thought no one could overhear.

“Wild creatures belong in the wild,” Coral Hadley told her son.

All the same, she had difficulty denying Isaac anything.

Why, she let the boy smuggle his pet into the rooms they let at the Crosbys’ boarding house, where he kept the blackbird in a wooden box beside his bed.

The real joy of the house they were building, as much for John as for anyone, was that it was, indeed, a farm.

They would have cows and horses to consider, rather than halibut and bluefish; predictable beasts at long last, and a large and glorious and predictable meadow as well.

Rather than the cruel ocean, there would be fences, and a barn, and a deep cistern of cold well water, the only water John’s boys would need or know, save for the pond at the rear of the property, where damselflies glided above the mallows in spring.

John Hadley had begun to talk about milk cows and crops.

He’d become fascinated with turnips, how hardy they were, how easy to grow, even in sandy soil.

In town, people laughed at him.

John Hadley knew this, and he didn’t care.

He’d traveled far enough in his lifetime.

Once, he’d been gone to the

But she’d told him to sell it and buy land.

She knew that was what he wanted.