Blood and Guts (17 page)

Authors: Richard Hollingham

Barnard had been studying the problems of heart transplants

for some time, although much of what he learnt was from other

surgeons rather than his own experiments. He travelled to see

Shumway at Stanford, and visited Longmore in London to witness

his heart-lung transplants on dogs. Barnard was personable, antiapartheid

and had something of a reputation – the handsome

young man's interest in affairs of the heart extended beyond pure

technical interest. While in London, he also attempted to seduce

one of Longmore's nurses (with some success apparently).

Barnard had learnt from the greats, and in an obscure South

African hospital, undisturbed by the authorities, he decided the

time was right to put his knowledge to the test. On 3 December

1967 he removed the beating heart of a twenty-five-year-old female

car crash victim, pronounced dead by a neurosurgeon. The recipient

of this fresh young heart was lying ready in an adjacent

operating theatre. Fifty-three-year-old diabetic Louis Washkansky

had already suffered several heart attacks and, quite frankly, did

not have long to live. The operation took two hours. Washkansky's

new heart started beating and kept beating. A day later he was

awake and talking. A few days later he was out of bed. Eighteen

days later he was dead.

Washkansky died of pneumonia. The drugs used to suppress his

immune system to prevent the heart being rejected had also left him

open to infection. But no one remembers Washkansky. Christiaan

Barnard was the hero of the day – an instant celebrity. Barnard

would be received by the pope, entertained by presidents and prime

ministers. He became the world's most eligible bachelor, dating a

string of beautiful and famous women.

Some of Barnard's rivals expressed more bitterness than others.

Longmore was pleased for him. Others muttered that they had

done all the work only for Barnard to take the glory. And what glory.

Who cared about the second man to fly across the Atlantic (Bert

Hinkler), to run the four-minute mile (John Landy) or to climb

Mount Everest (a matter of some debate)? Christiaan Barnard

would be the man in the history books.

But while Barnard had won the main prize, there was still a

degree of national pride at stake. If South Africa could do it, why

not the United States, Great Britain or France? The same bureaucrats

who had been so reluctant for Longmore's London hospital to

carry out a heart transplant were now asking what he was waiting for.

In January 1968 the second heart transplant was performed by

Adrian Kantrowitz in Brooklyn, so Shumway – the surgeon who had

spent so long developing heart transplant techniques – didn't even

get that honour. Shumway's operation was the fourth, and by the

time he came to operate later that month, Barnard had already

performed a second heart transplant.

The first British heart transplant (the world's tenth) took place

on 3 May 1968. The surgeon was Donald Ross (also a South African).

Longmore's role was to collect and deliver the donor heart. For some

reason this required a police escort through the streets of London.

In fact, the whole affair became a major public event, with a large

crowd of spectators, reporters and photographers gathered around

the door of the National Heart Hospital. It was, of course, a great

national achievement of a proud nation, etc., etc. However, the

patient, Frederick West, died of an 'overwhelming infection' forty-six

days later. And that was the problem: while the surgeons were getting

the glory, none of their patients were lasting very long. In the first few

years of heart transplant surgery, patients survived on average just

twenty-nine days. Despite all the euphoria, the awful truth was that

heart transplants were difficult, dangerous and complicated.

There are few surgeons as well known as the pioneers of heart

surgery. Heart surgeons were courageous, daring and bold. Heart

surgeons stood apart from the rest, almost every operation a matter

of life or death. When they succeeded, they saved lives. When they

failed, they had to be prepared to come back the next day and try

again. Many of them had personalities to match their abilities. Some

were self-confident, others were egotistical or arrogant. A few were

foolhardy or seemingly oblivious to risk. Most heart surgeons were

revered by their patients; many became national or international

celebrities – household names courted by the media, their faces on

the front page of

Time

magazine. Few people could name one of

today's heart surgeons, but then, thanks to pioneers such as Harken,

Bigelow, Lillehei,

*

Gibbon, Melrose and Barnard, major open-heart

surgery has finally become routine.

*

There is a curious footnote to Lillehei's career. In 1973 he was found guilty of tax evasion.

Although he was undoubtedly at fault, his crime was more one of carelessness than deliberate

evasion. He had always been bad at keeping financial records, and had performed many operations

for free. He carried out his last operation in 1973, but was to maintain a keen interest

in heart surgery until his death. At Lillehei's eightieth birthday party in 1998 many of

those invited to celebrate owed their lives to his expertise. He died a few months later, but a

great many of his patients live on.

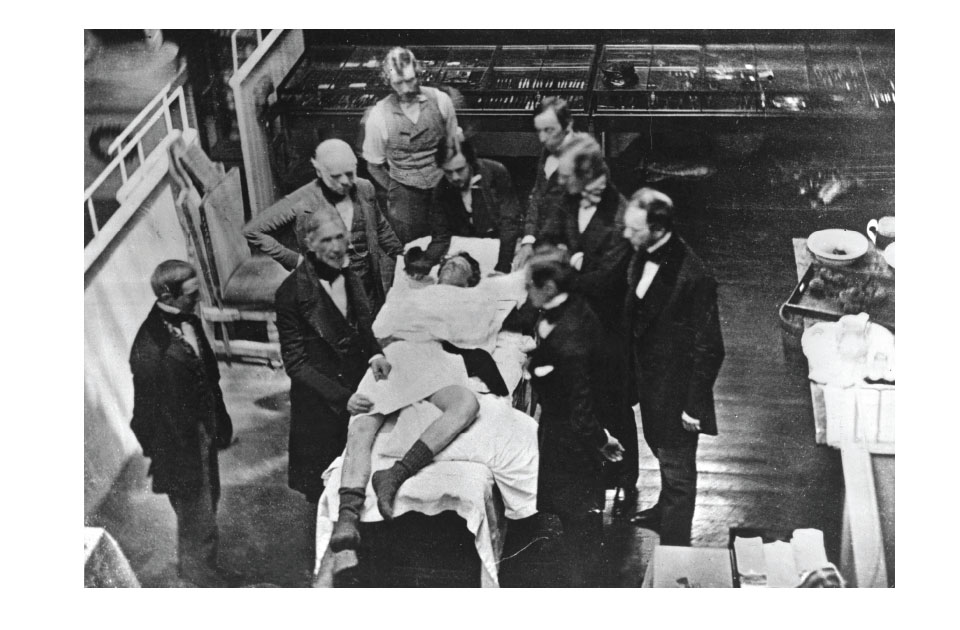

A photograph taken in 1848 of an operation to be carried out under anaesthetic at the

Boston General Hospital, Massachusetts. Judging from the sprawled position of the unconscious

patient, it looks as if he is about to lose a leg, although it is curious that he is wearing socks.

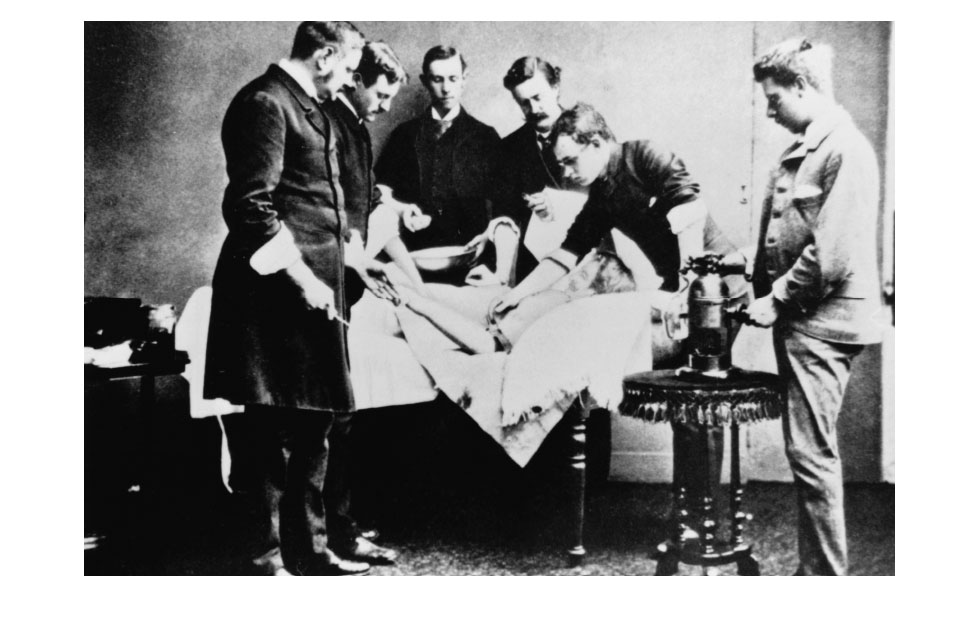

This photograph, taken in 1883 to demonstrate Lister's antiseptic

operating technique, appears to be somewhat staged. The carbolic spray is

being operated by the man on the right.

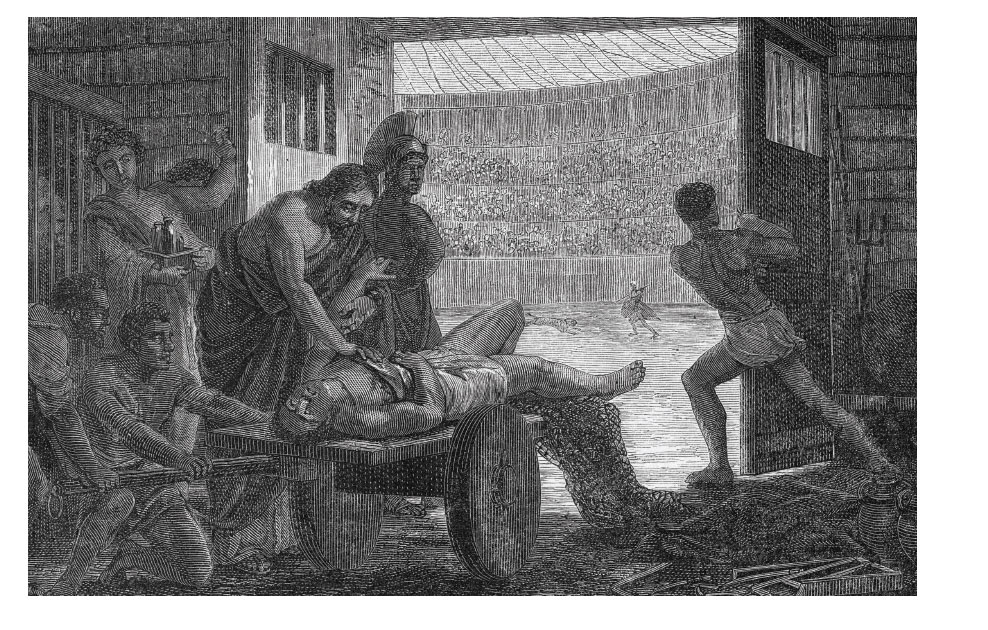

Galen attends to a wounded gladiator as the crowds bay for more blood.

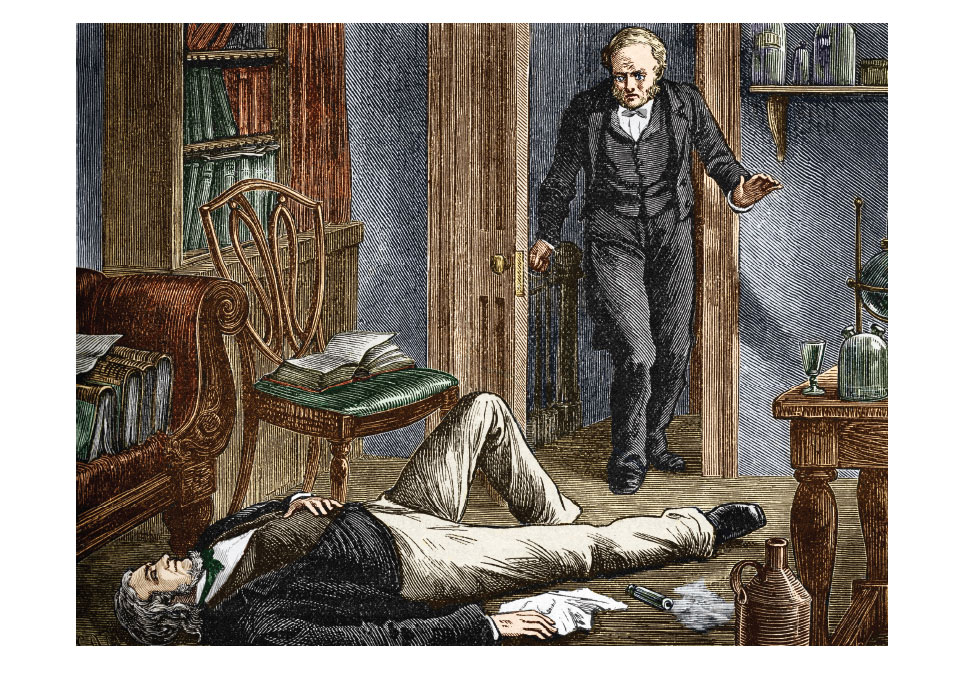

Simpson's butler walks in to find the surgeon collapsed on the floor –

another successful experiment on the properties of anaesthetics.

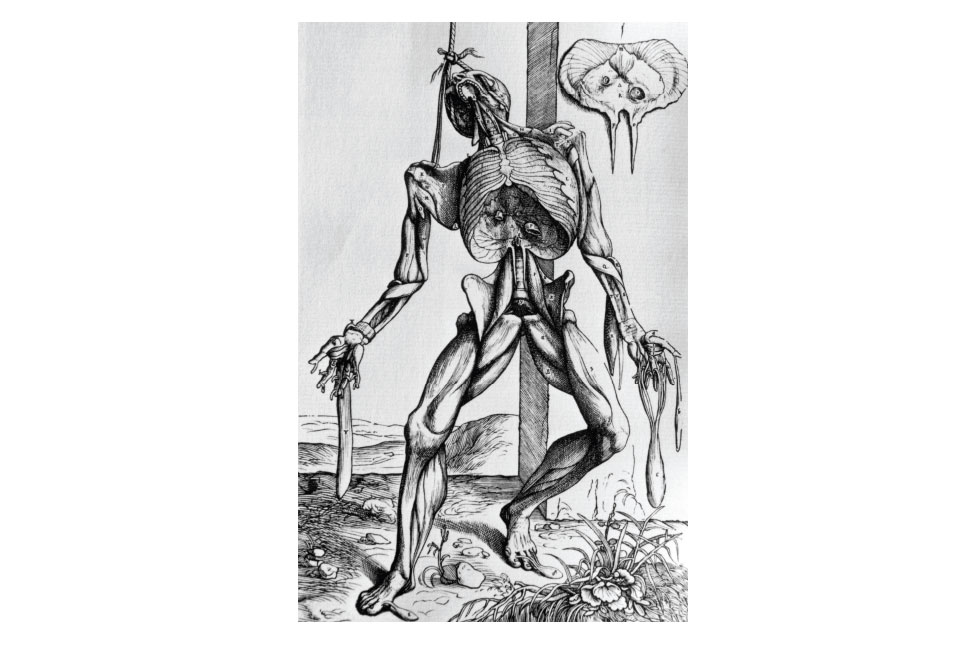

A 'muscleman' illustration from

Vesalius'

De Humani Corporis Fabrica

(1543)

alludes to his foray into body snatching.

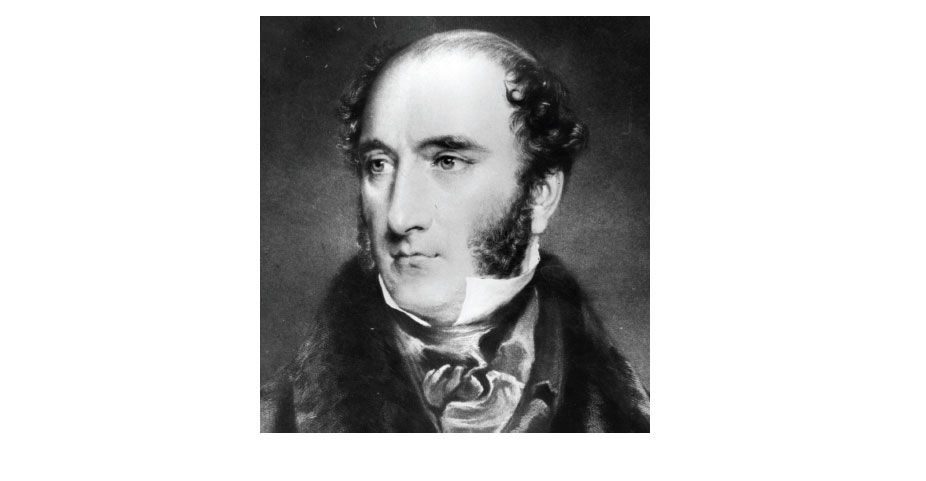

Robert Liston: 'sharp features,

sharp temper'.

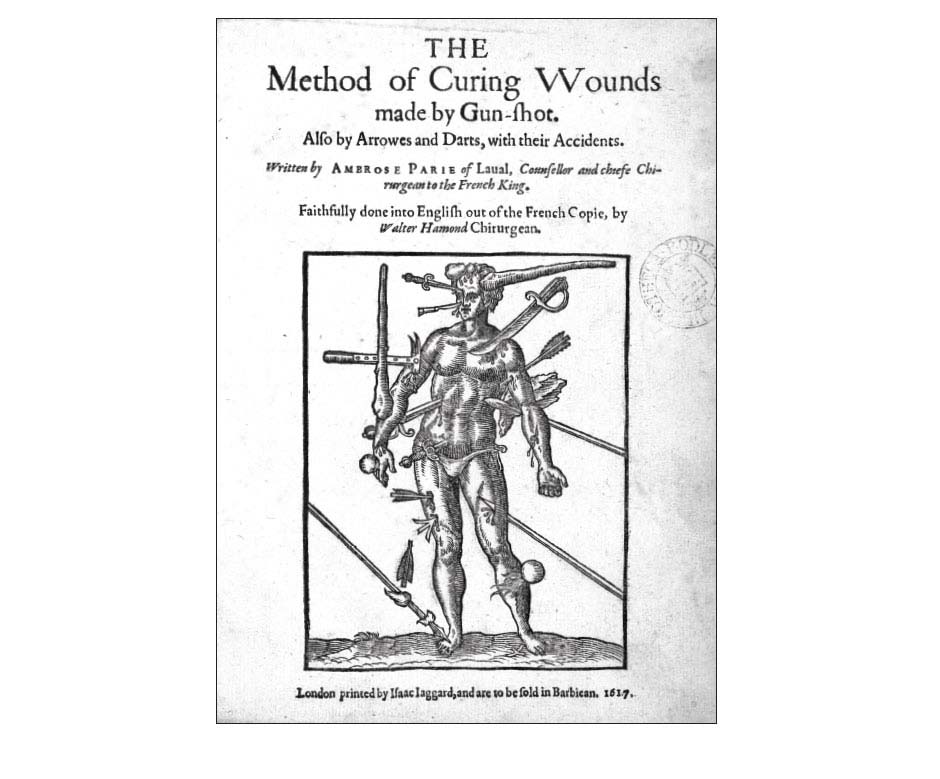

The man of

wounds. Suggesting

most of these were

curable seems wildly

optimistic.

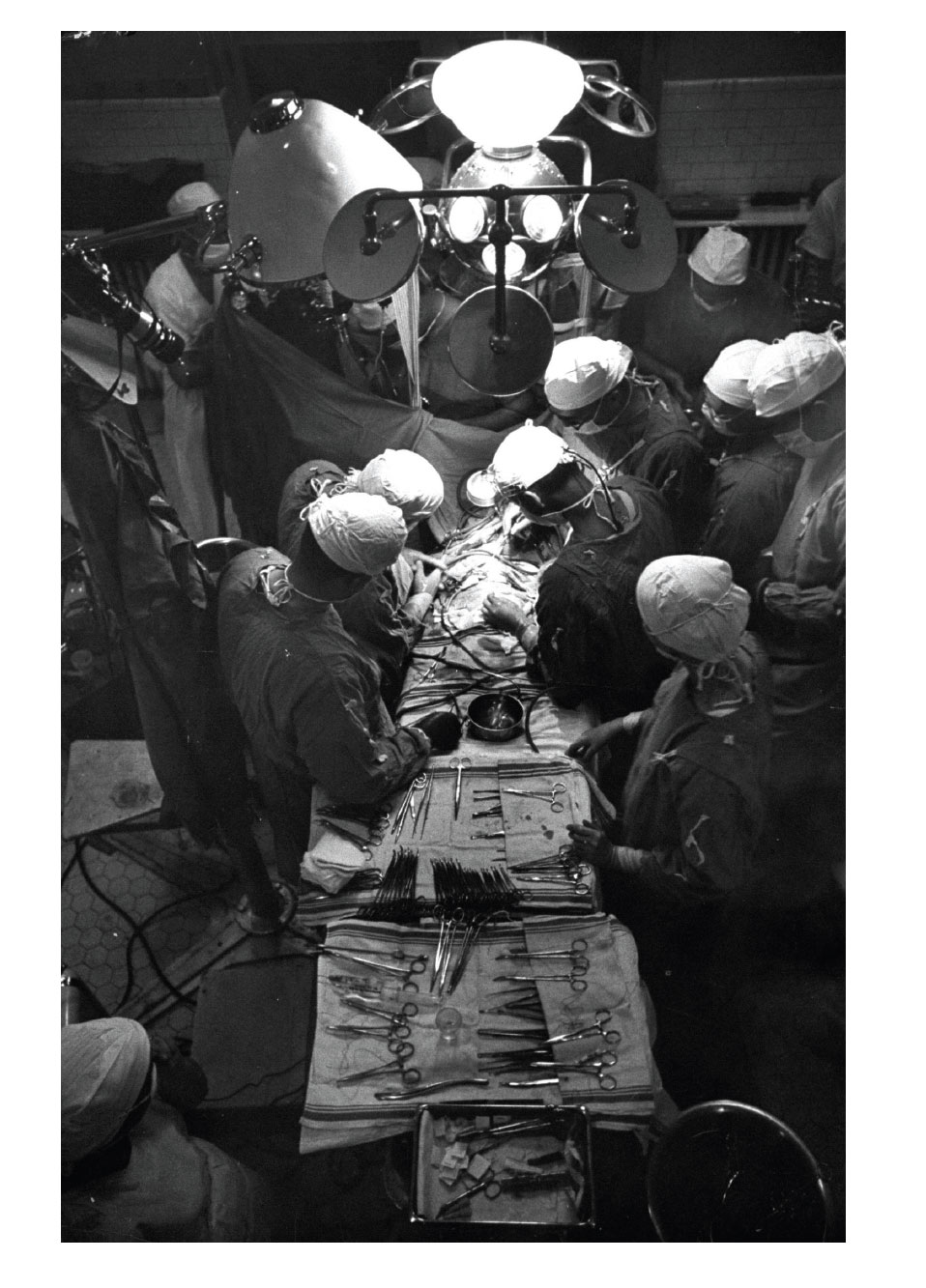

You can sense the intensity in the operating theatre

as Walter Lillehei performs open heart surgery using crosscirculation.

The first of these operations took place in 1954.