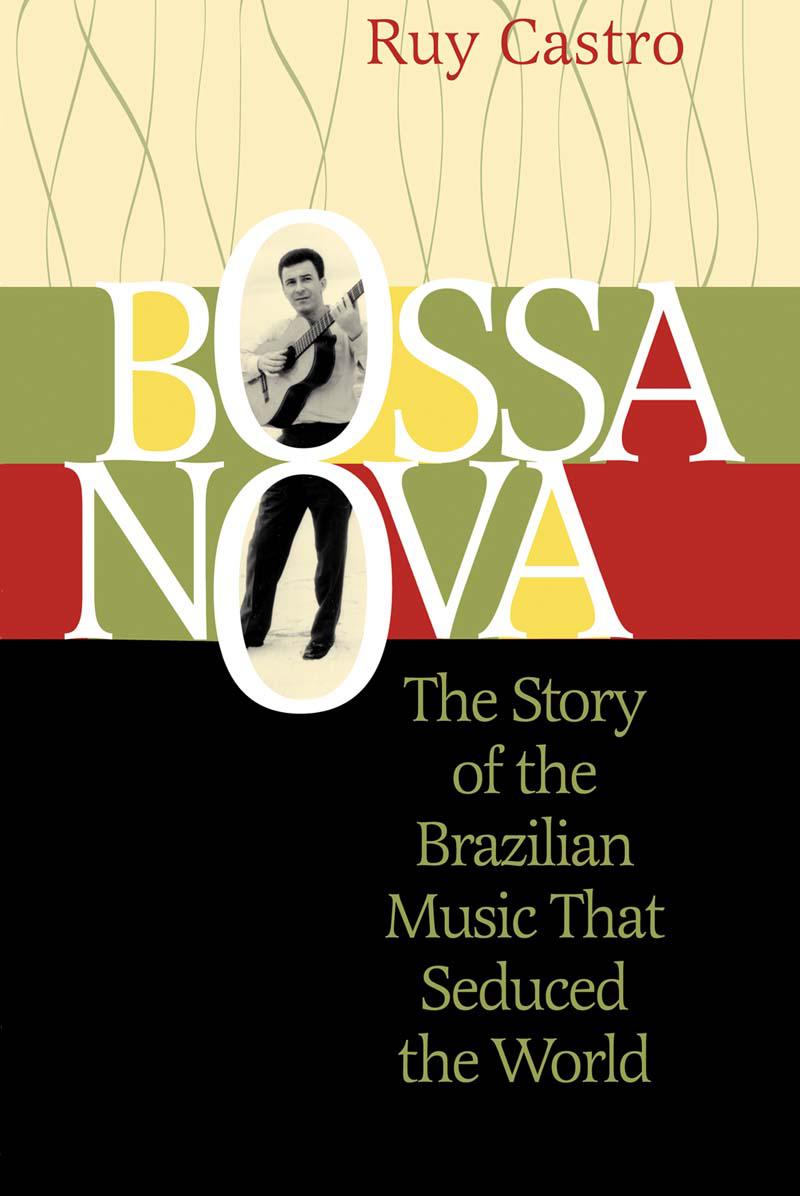

Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music That Seduced the World

Read Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music That Seduced the World Online

Authors: Ruy Castro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Castro, Ruy, 1948–

[Chega de saudade. English]

Bossa nova: the story of the Brazilian music that seduced the world / by Ruy Castro.

p. cm.

Includes discography (p.

337

) and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-55652-494-3

ISBN-10: 1-55652-494-3

1. Bossa nova (Music)—Brazil—History and criticism. I. Title.

ML3487.B7 C39 2000

781.64—dc21

00-031749

Cover design: Joan Sommers Design

Interior design: Mel Kupfer

©2000 by A Cappella Books and Ruy Castro

All rights reserved

First English-language edition

Published by A Cappella Books, an imprint of

Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, IL 60610

ISBN-13: 978-1-55652-494-3

ISBN-10: 1-55652-494-3

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2

First published in Brazil by Companhia Das Letras

©1990 by Ruy Castro

Translated by Lysa Salsbury

Foreword ©2000 by Julian Dibbell

This book is dedicated

to my daughters,

Pilar and Bianca.

Note to the Reader

At the end of this book a brief glossary will be found containing all musical and other Brazilian terms and names not defined in the text. For place names in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, see the maps on pages

xxiii–xvi.

Introduction and Acknowledgments

1. The Sounds That Came out of the Basement

2. Hot Times at the Lojas Murray

3. Battle of the Vocal Ensembles

4. The Mountains, the Sun, and the Sea

9. One Minute and Fifty-Nine Seconds That Changed Everything

13. Love, a Smile, and a Flower

14. It’s Salt, It’s Sun, It’s South

16. “Garota de Ipanema” (The Girl from Ipanema)

Epilogue: What Happened to Them

A Select Bossa Nova Discography

T

his is the story of bossa nova, and the young men and women who made the scene when they were between fifteen and thirty years old. It is also a book that aims to be as factual and objective as possible. It is clear that, as it was written by someone who has been listening to bossa nova music since it was given its name (someone who refused to conform when Brazil began to favor other exotic blends of music), a measured dose of enthusiasm has been added to the recipe—without the expression, I hope, of any bias, either in favor of or against, the path taken by any one participant. But human beings, like albums, have A and B sides, and the utmost effort was made to reveal both.

In order to compile this historical narrative, firsthand information was sought from the protagonists, assistants, and key players of each event described herein, cited in the list of acknowledgments. All important information was checked and rechecked with more than one source. The nature of certain pieces of information made it impossible to categorize them as originating from an “interview which took place on day X, in city Y, with Such-and-Such,” because this would transgress the ethical precept of safeguarding the anonymity of the source. However, even when it appears simple to figure out the source or sources for any piece of information, the responsibility for divulging them is mine. Sources who didn’t mind being identified are mentioned within the body of the text.

I think it important to note that I listened to

all

the recordings mentioned in the text, including extremely rare first records by Os Garotos da Lua (The Boys from the Moon), João Gilberto, João Donato, and Johnny Alf. I also had access to private tape recordings of João Gilberto, the first bossa nova performances in universities, the Bon Gourmet show, and a complete recording of the 1962 Carnegie Hall bossa nova concert.

Writing this book was facilitated by my prior acquaintance with several bossa nova celebrities, but it would not have been possible without the generosity and interest of more than a hundred people. For eighteen months, from January 1989 to August 1990, they patiently participated in long interviews, providing information, ransacking drawers, clarifying dates, locating records, copying tapes, tearing photos out of their albums, drawing maps, and giving detailed descriptions of homes, bars, and boats. Many of these interviews required three or four sessions, and almost all of them were granted in person, in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo—but there were also hundreds of phone calls to Salvador, Juazeiro, Porto Alegre, Vitória, Belo Horizonte, and even Lisbon. A few interviewees were consulted only by telephone and, without

even meeting me, provided valuable information. Others went to the trouble of replying to me in writing. My most heartfelt thanks to all of them. They were, in alphabetical order by last name:

Elba and João Luiz de Albuquerque; the late Lúcio Alves; Walter Arruda; Badeco of Os Cariocas; Billy Blanco; the late Ronaldo Bôscoli; Candinho (José Cândido de Mello Mattos); Heitor Carrillo; Achilles Chirol; Walter Clark; Luís Cláudio; Carlos Conde; Umberto Contardi; Haroldo Costa; Cravinho (Aminthas Jorge Cravo); the late Ivon Curi; Sônia Delfino; Reinaldo Di Giorgio Jr.; João Donato; Chico Feitosa; Juvenal Fernandes; Laurinha Figueiredo; Luvercy Fiorini; Janio de Freitas; Moysés Fuks; Paulo Garcez; João Gilberto; Sheila and the late Luís (“Chupeta”) Gomes; Christina Gurjão; Oswaldo Gurzoni; Júlio Hungria; the late Antonio Carlos Jobim; Jorge Karam; Alfonso Lafita; the late Nara Leão; Jacques and Lídia Libion; Paulo Lorgus; Carlos Lyra; the late Edison Machado; Tito Madi; Mariza Gata Mansa; Emília and Pacífico Mascarenhas; João Mário Medeiros; Acyr Bastos Mello; Cyrene Mendonça; Roberto Menescal; André Midani; Miéle; Miúcha; Paulo Moura; Álvaro de Moya; Tião Neto; Paulo César de Oliveira; Laura and Chico Pereira; Carlos Alberto Pingarilho; Armando Pittigliani; Nilo Queiroz; José Domingos Rafaelli; Álvaro Ramos; Flávio Ramos; the late Alberto Ruschel; Wanda Sá; Sabá; Maurício Sherman; Jonas Silva; Walter Silva; Raul de Souza; Mário Telles; José Ramos Tinhorão; Marcos Valle; David Drew Zingg; Ziraldo.

It is impossible to adequately express my gratitude to the following for the information they provided on the early João Gilberto: Belinha Abujamra, Miécio Caffé, Ieda Castiel, Clovis Moura, Merita Moura, Dr. Giuseppe Muccini, Dr. Dewilson de Oliveira, and Dona Dadainha de Oliveira Sá, all from Juazeiro, Bahia. Paulo Diniz, Dr. Alberto Fernandes, Glênio Reis, and the late Dona Boneca Regina told me about his days in Porto Alegre, and Oswaldo Carneiro, Henrique Fernando Cruz, and Maria do Carmo Queiroz provided decisive information on the Sinatra-Farney Fan Club.

I also owe special thanks to Leon Barg, of Curitiba, for his fabulous collection of 78 r.p.m.s; Sérgio Cabral; Ricardo Carvalho, for providing his dedicated research on Vinícius de Moraes; Almir Chediak; Isabel Leão Diégues, for allowing access to her mother Nara’s files; and Arnaldo de Souteiro, who seems to know everything there is to know about the international development of bossa nova. And many thanks to friends like Rita Kauffman and the dear, late Giovani Mafra e Silva, whose help in Rio was invaluable to this book, as well as to Alice Sampaio and Sueli Queiroz, in São Paulo, for many personal reasons.

“S

top telling stories,” said Dionne Warwick in the midst of a 1966 visit to Rio de Janeiro. “Everybody knows it was Burt Bacharach who invented bossa nova.” She actually believed this, evidently, but don’t be too quick to snicker. Her notion of the music’s origins may have been all wet, but at least she had one.

For the rest of us Americans, as a rule, bossa nova is a music laced with meaning but void of history. We locate it historically, if we do, not within any context of its own, but as a scene in one of our favorite pop-cultural narratives—a brief Brazilian seduction on the eve of a much more momentous British invasion. In the role of seductress: “The Girl from Ipanema,” composed by Antonio Carlos “Tom” Jobim, sung with unnerving cool by Astrud Gilberto, fortified by Stan Getz’s throaty sax, and anchored by the telegraphically syncopated guitar of Astrud’s husband, bossa nova icon João Gilberto. Hurling itself to the top of the charts in early 1964, that brilliant single charmed the U.S. public into one last fling with jazzy sophistication before Beatlemania decreed the reign of rock’s vulgar beauty. It was a melancholy farewell to Camelot, to the pop ideal of urbane elegance, and inevitably, to bossa nova’s own short moment at the center of our attention.