Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (726 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

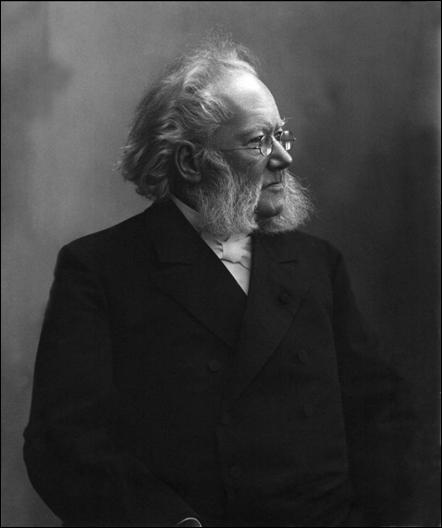

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

Rubek himself is the chief figure in this drama, and, strangely enough, the most conventional. Certainly, when contrasted with his Napoleonic predecessor, John Gabriel Borkman, lie is a mere shadow. It must be borne in mind, however, that Borkman is alive, actively, energetically, restlessly alive, all through the play to the end, when he dies; whereas Arnold Rubek is dead, almost hopelessly dead, until the end, when he comes to life. Notwithstanding this, he is supremely interesting, not because of himself, but because of his dramatic significance. Ibsen’s drama, as I have said, is wholly independent of his characters. They may be bores, but the drama in which they live and move is invariably powerful. Not that Rubek is a bore by any means! He is infinitely more interesting in himself than Torvald Helmer or Tesman, both of whom possess certain strongly-marked characteristics. Arnold Rubek is, on the other hand, not intended to be a genius, as perhaps Eljert Lovborg is. Had he been a genius like Eljert he would have understood in a truer way the value of his life. But, as we are to suppose, the facts that he is devoted to his art and that he has attained to a degree of mastery in it — mastery of hand linked with limitation of thought — tell us that there may be lying dormant in him a capacity for greater life, which may be exercised when he, a dead man, shall have risen from among the dead.

The only character whom I have neglected is the inspector of the baths, and I hasten to do him tardy, but scant, justice. He is neither more nor less than the average inspector of baths. But he is that.

So much for the characterization, which is at all times profound and interesting. But apart from the characters in the play, there are some noteworthy points in the frequent and extensive side- issues of the line of thought. The most salient of these is what seems, at first sight, nothing more than an accidental scenic feature. I allude to the environment of the drama. One cannot but observe in Ibsen’s later work a tendency to get out of closed rooms. Since

Hedda Gabier

this tendency is most marked. The last act of

The Master Builder

and the last act of

John Gabriel Borkman

take place in the open air. But in this play the three acts are

al fresco.

To give heed to such details as these in the drama may be deemed ultra-Boswellian fanaticism. As a matter of fact it is what is barely due to the work of a great artist. And this feature, which is so prominent, does not seem to me altogether without its significance.

Again, there has not been lacking in the last few social dramas a fine pity for men — a note nowhere audible in the uncompromising rigour of the early eighties. Thus in the conversion of Rubek’s views as to the girl-figure in his masterpiece, The Resurrection Day’, there is involved an all-embracing philosophy, a deep sympathy with the cross-purposes and contradictions of life, as they may be reconcilable with a hopeful awakening — when the manifold travail of our poor humanity may have a glorious issue. As to the drama itself, it is doubtful if any good purpose can be served by attempting to criticize it. Many things would tend to prove this. Henrik Ibsen is one of the world’s great men before whom criticism can make but feeble show. Appreciation, hearkening is the only true criticism. Further, that species of criticism which calls itself dramatic criticism is a needless adjunct to his plays. When the art of a dramatist is perfect the critic is superfluous. Life is not to be criticized, but to be faced and lived. Again, if any plays demand a stage they are the plays of Ibsen. Not merely is this so because his plays have so much in common with the plays of other men that they were not written to cumber the shelves of a library, but because they are so packed with thought. At some chance expression the mind is tortured with some question, and in a flash long reaches of life are opened up in vista, yet the vision is momentary unless we stay to ponder on it. It is just to prevent excessive pondering that Ibsen requires to be acted. Finally, it is foolish to expect that a problem, which has occupied Ibsen for nearly three years, will unroll smoothly before our eyes on a first or second reading. So it is better to leave the drama to plead for itself. But this at least is clear, that in this play Ibsen has given us nearly the very best of himself. The action is neither hindered by many complexities, as in

The Pillars of Society

, nor harrowing in its simplicity, as in

Ghosts.

We have whimsicality, bordering on extravagance, in the wild Ulfheim, and subtle humour in the sly contempt which Rubek and Maja entertain for each other. But Ibsen has striven to let the drama have perfectly free action. So he has not bestowed his wonted pains on the minor characters. In many of his plays these minor characters are matchless creations. Witness Jacob Engstrand, Tônnesen, and the demonic Molvik! But in this play the minor characters are not allowed to divert our attention.

On the whole,

When We Dead A waken

may rank with the greatest of the author’s work — if, indeed, it be not the greatest. It is described as the last of the series, which began with

A Doll’s House

— a grand epilogue to its ten predecessors. Than these dramas, excellent alike in dramaturgic skill, characterization, and supreme interest, the long roll of drama, ancient or modern, has few things better to show.

James A. Joyce

e

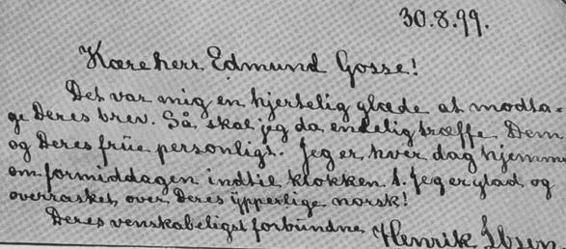

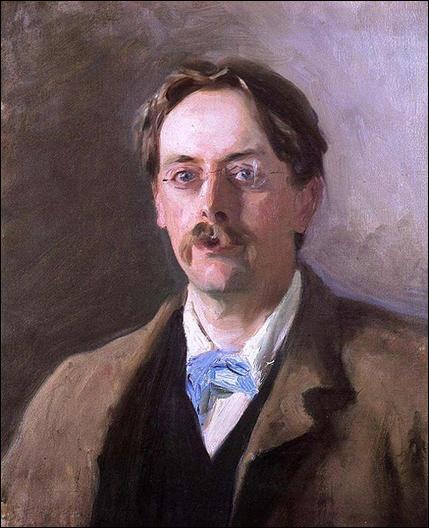

Edmund Gosse (1849–1928) was an English poet, author and critic, whose father was a naturalist and his mother an illustrator that published a number of books of poetry. His childhood was initially happy as they spent their summers in Devon where his father was developing the ideas which gave rise to the popularity of the marine aquarium. After his mother died of breast cancer, they moved to Devon, where life with his father became increasingly strained by his parent’s expectations that he should follow in his religious tradition. The son was sent to a boarding school where he began to develop his own interests in literature.

Gosse started his career as assistant librarian at the British Museum from 1867. An early book of poetry published with a friend, John Arthur Blaikie, gave Gosse an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Trips to Denmark and Norway in 1872–74, where he visited Hans Christian Andersen and Frederik Paludan-Müller, led to publishing success with reviews of Ibsen’s plays in the Cornhill Magazine. Gosse was impressed by the powerful representation of realism in Scandinavian literature, for which he wrote numerous reviews in a variety of publications.

He was responsible for introducing Henrik Ibsen’s works to the British public, dedicating his time to mastering the Norwegian language in order to enjoy the true essence of Ibsen’s use of language.

Gosse and William Archer collaborated in translating

Hedda Gabler

and

The Master Builder,

producing

translations that were performed many times throughout the 20th century. In

Edmund Gosse by John Singer Sargent, 1886

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

CHAPTER III. LIFE IN BERGEN (1852-57)

CHAPTER IV. THE SATIRES (1857-67)

CHAPTER IX. PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS

CHAPTER X. INTELLECTUAL CHARACTERISTICS

PREFACE

Numerous and varied as have been the analyses of Ibsen’s works published, in all languages, since the completion of his writings, there exists no biographical study which brings together, on a general plan, what has been recorded of his adventures as an author. Hitherto the only accepted Life of Ibsen has been

Et literaert Livsbillede

, published in 1888 by Henrik Jaeger; of this an English translation was issued in 1890. Henrik Jaeger (who must not be confounded with the novelist, Hans Henrik Jaeger) was a lecturer and dramatic critic, residing near Bergen, whose book would possess little value had he not succeeded in persuading Ibsen to give him a good deal of valuable information respecting his early life in that city. In its own day, principally on this account, Jaeger’s volume was useful, supplying a large number of facts which were new to the public. But the advance of Ibsen’s activity, and the increase of knowledge since his death, have so much extended and modified the poet’s history that

Et literaert Livsbillede

has become obsolete.

The principal authorities of which I have made use in the following pages are the minute bibliographical

Oplysninger

of J. B. Halvorsen, marvels of ingenious labor, continued after Halvorsen’s death by Sten Konow (1901); the

Letters of Henrik Ibsen

, published in two volumes, by H. Koht and J. Elias, in 1904, and now issued in an English translation (Hodder & Stoughton); the recollections and notes of various friends, published in the periodicals of Scandinavia and Germany after his death; T. Blanc’s

Et Bidrag til den Ibsenskte Digtnings Scenehistorie

(1906); and, most of all, the invaluable

Samliv med Ibsen

(1906) of Johan Paulsen. This last-mentioned writer aspires, in measure, to be Ibsen’s Boswell, and his book is a series of chapters reminiscent of the dramatist’s talk and manners, chiefly during those central years of his life which he spent in Germany. It is a trivial, naive and rather thin production, but it has something of the true Boswellian touch, and builds up before us a lifelike portrait.

From the materials, too, collected for many years past by Mr. William Archer, I have received important help. Indeed, of Mr. Archer it is difficult for an English student of Ibsen to speak with moderation. It is true that thirty-six years ago some of Ibsen’s early metrical writings fell into the hands of the writer of this little volume, and that I had the privilege, in consequence, of being the first person to introduce Ibsen’s name to the British public. Nor will I pretend for a moment that it is not a gratification to me, after so many years and after such surprising developments, to know that this was the fact. But, save for this accident of time, it was Mr. Archer and no other who was really the introducer of Ibsen to English readers. For a quarter of a century he was the protagonist in the fight against misconstruction and stupidity; with wonderful courage, with not less wonderful good temper and persistency, he insisted on making the true Ibsen take the place of the false, and on securing for him the recognition due to his genius. Mr. William Archer has his reward; his own name is permanently attached to the intelligent appreciation of the Norwegian playwright in England and America.

In these pages, where the space at my disposal was so small, I have not been willing to waste it by repeating the plots of any of those plays of Ibsen which are open to the English reader. It would please me best if this book might be read in connection with the final edition of

Ibsen’s Complete Dramatic Works

, now being prepared by Mr. Archer in eleven volumes (W. Heinemann, 1907). If we may judge of the whole work by those volumes of it which have already appeared, I have little hesitation in saying that no other foreign author of the second half of the nineteenth century has been so ably and exhaustively edited in English as Ibsen has been in this instance.

The reader who knows the Dano-Norwegian language may further be recommended to the study of Carl Naerup’s

Norsk Litteraturhistories siste Tidsrum

(1905), a critical history of Norwegian literature since 1890, which is invaluable in giving a notion of the effect of modern ideas on the very numerous younger writers of Norway, scarcely one of whom has not been influenced in one direction or another by the tyranny of Ibsen’s personal genius. What has been written about Ibsen in England and France has often missed something of its historical value by not taking into consideration that movement of intellectual life in Norway which has surrounded him and which he has stimulated. Perhaps I may be allowed to say of my little book that this side of the subject has been particularly borne in mind in the course of its composition.

E. G.

KLOBENSTEIN.