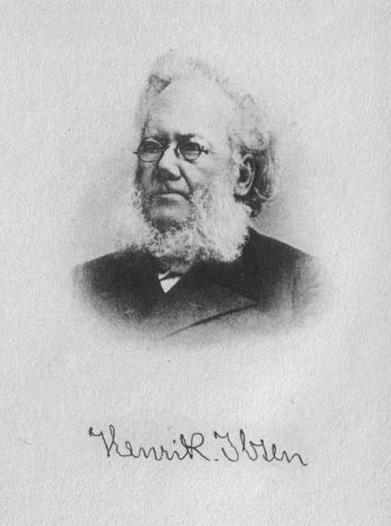

Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (739 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

A Doll’s House

was Ibsen’s first unqualified success. Not merely was it the earliest of his plays which excited universal discussion, but in its construction and execution it carried out much further than its immediate precursors Ibsen’s new ideal as an unwavering realist. Mr. Arthur Symons has well said [Note: The

Quarterly Review

for October, 1906.] that “

A Doll’s House

is the first of Ibsen’s plays in which the puppets have no visible wires.” It may even be said that it was the first modern drama in which no wires had been employed. Not that even here the execution is perfect, as Ibsen afterwards made it. The arm of coincidence is terribly shortened, and the early acts, clever and entertaining as they are, are still far from the inevitability of real life. But when, in the wonderful last act, Nora issues from her bedroom, dressed to go out, to Helmer’s and the audience’s stupefaction, and when the agitated pair sit down to “have it out,” face to face across the table, then indeed the spectator feels that a new thing has been born in drama, and, incidentally, that the “well-made play” has suddenly become as dead as Queen Anne. The grimness, the intensity of life, are amazing in this final scene, where the old happy ending is completely abandoned for the first time, and where the paradox of life is presented without the least shuffling or evasion.

It was extraordinary how suddenly it was realized that

A Doll’s House

was a prodigious performance. All Scandinavia rang with Nora’s “declaration of independence.” People left the theatre, night after night, pale with excitement, arguing, quarrelling, challenging. The inner being had been unveiled for a moment, and new catchwords were repeated from mouth to mouth. The great statement and reply—”No man sacrifices his honor, even for one he loves,” “Hundreds of thousands of women have done so!” — roused interminable discussion in countless family circles. The disputes were at one time so violent as to threaten the peace of households; a school of imitators at once sprang up to treat the situation, from slightly different points of view, in novel, poem and drama. [Note: The reader who desires to obtain further light on the technical quality of

A Doll’s House

can do no better than refer to Mr. William Archer’s elaborate analysis of it (

Fortnightly Review

, July, 1906.)]

The universal excitement which Ibsen had vainly hoped would be awakened by

The Pillars of Society

came, when he was not expecting it, to greet

A Doll’s House

. Ibsen was stirred by the reception of his latest play into a mood rather different from that which he expressed at any other period. As has often been said, he did not pose as a prophet or as a reformer, but it did occur to him now that he might exercise a strong moral influence, and in writing to his German translator, Ludwig Passarge, he said (June 16, 1880):

Everything that I have written has the closest possible connection with what I have lived through, even if it has not been my own personal experience; in every new poem or play I have aimed at my own spiritual emancipation and purification — for a man shares the responsibility and the guilt of the society to which he belongs.

It was in this spirit of unusual gravity that he sat down to the composition of

Ghosts

. There is little or no record of how he occupied himself at Munich and Berchtesgaden in 1880, except that in March he began to sketch, and then abandoned, what afterwards became

The Lady from the Sea

. In the autumn of that year, indulging once more his curious restlessness, he took all his household gods and goods again to Rome. His thoughts turned away from dramatic art for a moment, and he planned an autobiography, which was to deal with the gradual development of his mind, and to be called

From Skien to Rome

. Whether he actually wrote any of this seems uncertain; that he should have planned it shows a certain sense of maturity, a suspicion that, now in his fifty-third year, he might be nearly at the end of his resources. As a matter of fact, he was just entering upon a new inheritance. In the summer of 1881 he went, as usual now, to Sorrento, and there [Note: So the authorities state: but in an unpublished letter to myself, dated Rome, November 26, 1880, I find Ibsen saying, “Just now I am beginning to exercise my thoughts over a new drama; I hope I shall finish it in the course of next summer.” It seems to have been already his habit to meditate long about a subject before it took any definite literary form in his mind.] the plot of

Ghosts

revealed itself to him. This work was composed with more than Ibsen’s customary care, and was published at the beginning of December, in an edition of ten thousand copies.

Before the end of 1881 Ibsen was aware of the terrific turmoil which

Ghosts

had begun to occasion. He wrote to Passarge: “My new play has now appeared, and has occasioned a terrible uproar in the Scandinavian press. Every day I receive letters and newspaper articles decrying or praising it. I consider it absolutely impossible that any German theatre will accept the play at present. I hardly believe that they will dare to play it in any Scandinavian country for some time to come.” It was, in fact, not acted publicly anywhere until 1883, when the Swedes ventured to try it, and the Germans followed in 1887. The Danes resisted it much longer.

Ibsen declared that he was quite prepared for the hubbub; he would doubtless have been much disappointed if it had not taken place; nevertheless, he was disconcerted at the volume and the violence of the attacks. Yet he must have known that in the existing condition of society, and the limited range of what was then thought a defensible criticism of that condition,

Ghosts

must cause a virulent scandal. There has been, especially in Germany, a great deal of medico- philosophical exposure of the under-side of life since 1880. It is hardly possible that, there, or in any really civilized country, an analysis of the causes of what is, after all, one of the simplest and most conventional forms of hereditary disease could again excite such a startling revulsion of feeling. Krafft-Ebing and a crew of investigators, Strindberg, Brieux, Hauptmann, and a score of probing playwrights all over the Continent, have gone further and often fared much worse than Ibsen did when he dived into the family history of Kammerherre Alving. When we read

Ghosts

to-day we cannot recapture the “new shudder” which it gave us a quarter of a century ago. Yet it must not be forgotten that the publication of it, in that hide-bound time, was an act of extraordinary courage. Georg Brandes, always clearsighted, was alone in being able to perceive at once that

Ghosts

was no attack on society, but an effort to place the responsibilities of men and women on a wholesomer and surer footing, by direct reference to the relation of both to the child.

When the same eminent critic, however, went on to say that

Ghosts

was “a poetic treatment of the question of heredity,” it was more difficult to follow him. Now that the flash and shock of the playwright’s audacity are discounted, it is natural to ask ourselves whether, as a work of pure art,

Ghosts

stands high among Ibsen’s writings. I confess, for my own part, that it seems to me deprived of “poetic” treatment, that is to say, of grace, charm and suppleness, to an almost fatal extent. It is extremely original, extremely vivid and stimulating, but, so far as a foreigner may judge, the dialogue seems stilted and uniform, the characters, with certain obvious exceptions, rather types than persons. In the old fighting days it was necessary to praise

Ghosts

with extravagance, because the vituperation of the enemy was so stupid and offensive, but now that there are no serious adversaries left, cooler judgment admits — not one word that the idiot-adversary said, but — that there are more convincing plays than

Ghosts

in Ibsen’s repertory.

Up to this time, Ibsen had been looked upon as the mainstay of the Conservative party in Norway, in opposition to Björnson, who led the Radicals. But the author of

Ghosts

, who was accused of disseminating anarchism and nihilism, was now smartly drummed out of the Tory camp without being welcomed among the Liberals. Each party was eager to disown him. He was like Coriolanus, when he was deserted by nobles and people alike, and

suffer’d by the voice of slaves to be Whoop’d out of Rome.

The situation gave Ibsen occasion, from the perspective of his exile, to form some impressions of political life which were at once pungent and dignified:

“I am more and more confirmed” [he said, Jan, 3, 1882] “in my belief that there is something demoralizing in politics and parties. I, at any rate, shall never be able to join a party which has the majority on its side. Björnson says, ‘The majority is always right’; and as a practical politician he is bound, I suppose, to say so. I, on the contrary, of necessity say, ‘The minority is always right.’“

In order to place this view clearly before his countrymen, he set about composing the extremely vivid and successful play, perhaps the most successful pamphlet-play that ever was written, which was to put forward in the clearest light the claim of the minority. He was very busy with preparations for it all through the summer of 1882, which he spent at what was now to be for many years his favorite summer resort, Gossensass in the Tyrol, a place which is consecrated to the memory of Ibsen in the way that Pornic belongs to Robert Browning and the Bel Alp to Tyndall, holiday homes in foreign countries, dedicated to blissful work without disturbance. Here, at a spot now officially named the “Ibsenplatz,” he composed

The Enemy of the People

, engrossed in his invention as was his wont, reading nothing and thinking of nothing but of the persons whose history he was weaving. Oddly enough, he thought that this, too, was to be a “placable” play, written to amuse and stimulate, but calculated to wound nobody’s feelings. The fact was that Ibsen, like some ocelot or panther of the rocks, had a paw much heavier than he himself realized, and his “play,” in both senses, was a very serious affair, when he descended to sport with common humanity.

Another quotation, this time from a letter to Brandes, must be given to show what Ibsen’s attitude was at this moment to his fatherland and to his art:

“When I think how slow and heavy and dull the general intelligence is at home, when I notice the low standard by which everything is judged, a deep despondency comes over me, and it often seems to me that I might just as well end my literary activity at once. They really do not need poetry at home; they get along so well with the party newspapers and the

Lutheran Weekly

.”

If Ibsen thought that he was offering them “poetry” in

The Enemy of the People

, he spoke in a Scandinavian sense. Our criticism has never opened its arms wide enough to embrace all imaginative literature as poetry, and in the English sense nothing in the world’s drama is denser or more unqualified prose than

The Enemy of the People

, without a tinge of romance or rhetoric, as “unideal” as a blue-book. It is, nevertheless, one of the most certainly successful of its author’s writings; as a stage-play it rivets the attention; as a pamphlet it awakens irresistible sympathy; as a specimen of dramatic art, its construction and evolution are almost faultless. Under a transparent allegory, it describes the treatment which Ibsen himself had received at the hands of the Norwegian public for venturing to tell them that their spa should be drained before visitors were invited to flock to it. Nevertheless, the playwright has not made the mistake of identifying his own figure with that of Dr. Stockmann, who is an entirely independent creation. Mr. Archer has compared the hero with Colonel Newcome, whose loquacious amicability he does share, but Stockmann’s character has much more energy and initiative than Colonel Newcome’s, whom we could never fancy rousing himself “to purge society.”

Ibsen’s practical wisdom in taking the bull by the horns in his reply to the national reception of

Ghosts

was proved by the instant success of

The Enemy of the People

. Presented to the public in this new and audacious form, the problem of a “moral water-supply” struck sensible Norwegians as less absurd and less dangerous than they had conceived it to be. The reproof was mordant, and the worst offenders crouched under the lash.

Ghosts

itself was still, for some time, tabooed, but

The Enemy of the People

received a cordial welcome, and has remained ever since one of the most popular of Ibsen’s writings. It is still extremely effective on the stage, and as it is lightened by more humor than the author is commonly willing to employ, it attracts even those who are hostile to the intrusion of anything solemn behind the footlights.