Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (744 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

On his seventieth birthday, March 20, 1898, Ibsen received the felicitations of the world. It is pleasing to relate that a group of admirers in England, a group which included Mr. Asquith, Mr. J. M. Barrie, Mr. Thomas Hardy, Mr. Henry Arthur Jones, Mr. Pinero and Mr. Bernard Shaw took part in these congratulations and sent Ibsen a handsome set of silver plate, this being an act which, it had been discovered, he particularly appreciated. The bearer of this gift was the earliest of the long stream of visitors to arrive on the morning of the poet’s birthday, and he found Ibsen in company with his wife, his son, his son’s wife (Björnson’s daughter), and his little grandson, Tankred. The poet’s surprise and pleasure were emphatic. A deputation from the Storthing, headed by the Leader of the House, deputations representing the University, the various Christiania Theatres, and other official or academic bodies arrived at intervals during the course of the day; and all the afternoon Ibsen was occupied in taking these hundreds of visitors, in parties, up to the case containing the English tribute, in showing the objects and in explaining their origin. There could be no question that the gift gave genuine pleasure to the recipient; it was the first, as it was to be the last, occasion on which any public testimony to English appreciation of his genius found its way to Ibsen’s door.

Immediately after the birthday festivities, which it was observed had fatigued him, Ibsen started on a visit to Copenhagen, where he was received by the aged King of Denmark, and to Stockholm, where he was overpowered with ovations from all classes. There can be no doubt that this triumphal progress, though deeply grateful to the aged poet’s susceptibilities, made a heavy drain upon his nervous resources. When he returned to Norway, indeed, he was concealed from all visitors at his physician’s orders, and it is understood that he had some kind of seizure. It was whispered that he would write no more, and the biennial drama, due in December, 1898, did not make its appearance. His stores of health, however, were not easily exhausted; he rested for several months, and then he was seen once more in Carl Johans Gade, smiling; in his usual way, and entirely recovered. It was announced that winter that he was writing his reminiscences, but nothing more was heard of any such book.

He was able to take a vivid interest in the preparations for the National Norwegian Theatre in Christiania, which was finally opened by the King of Sweden and Norway on September 1, 1899. Early in the morning, colossal bronze statues of Ibsen and Björnson were unveiled in front of the theatre, and the poets, now, unfortunately, again not on the best of terms, were seen making vast de*tours for the purpose of satisfying their curiosity, and yet not meeting one another in flesh or in metal. The first night, to prevent rivalry, was devoted to antiquarianism, and to the performance of extracts from the plays of Holberg. Ibsen and Björnson occupied the centre of the dress circle, sitting uplifted in two gilded fauteuils and segregated by a vast garland of red and white roses. They were the objects of universal attention, and the King seemed never to have done smiling and bowing to the two most famous of his Norwegian subjects.

The next night was Ibsen’s fete, and he occupied, alone, the manager’s box. A poem in his honor, by Niels Collet Vogt, was recited by the leading actor, who retired, and then rushed down the empty stage, with his arms extended, shouting “Long live Henrik Ibsen.” The immense audience started to its feet and repeated the words over and over again with deafening fervor. The poet appeared to be almost overwhelmed with emotion and pleasure; at length, with a gesture which was quite pathetic, smiling through his tears, he seemed to beg his friends to spare him, and the plaudits slowly ceased.

An Enemy of the People

was then admirably performed. At the close of every act Ibsen was called to the front of his box, and when the performance was over, and the actors had been thanked, the audience turned to him again with a sort of affectionate ferocity. Ibsen was found to have stolen from his box, but he was waylaid and forcibly carried back to it. On his reappearance, the whole theatre rose in a roar of welcome, and it was with difficulty that the aged poet, now painfully exhausted from the strain of an evening of such prolonged excitement, could persuade the public to allow him to withdraw. At length he left the theatre, walking slowly, bowing and smiling, down a lane cleared for him, far into the street, through the dense crowd of his admirers. This astonishing night, September 2, 1899, was the climax of Ibsen’s career.

During all this time Ibsen was secretly at work on another drama, which he intended as the epilogue to his earlier dramatic work, or at least to all that he had written since

The Pillars of Society

. This play, which was his latest, appeared, under the title of

When We Dead Awaken

, in December, 1899 (with 1900 on the title-page). It was simultaneously published, in very large editions, in all the principal languages of Europe, and it was acted also, but it is impossible to deny that, whether in the study or on the boards, it proved a disappointment. It displayed, especially in its later acts, many obvious signs of the weakness incident on old age.

When it is said that

When We Dead Awaken

was not worthy of its predecessors, it should be explained that no falling off was visible in the technical cleverness with which the dialogue was built up, nor in the wording of particular sentences. Nothing more natural or amusing, nothing showing greater, command of the resources of the theatre, had ever been published by Ibsen himself than the opening act of

When We Dead Awaken

. But there was certainly in the whole conception a cloudiness, an ineffectuality, which was very little like anything that Ibsen had displayed before. The moral of the piece was vague, the evolution of it incoherent, and indeed in many places it seemed a parody of his earlier manner. Not Mr. Anstey Guthrie’s inimitable scenes in

Mr. Punch’s Ibsen

were more preposterous than almost all the appearances of Irene after the first act of

When We Dead Awaken

.

It is Irene who describes herself as dead, but awakening in the society of Rubek, whilst Maia, the little gay soulless creature whom the great sculptor has married, and has got heartily tired of, goes up to the mountains with Ulpheim the hunter, in pursuit of the free joy of life. At the close, the assorted couples are caught on the summit of an exceeding high mountain by a snowstorm, which opens to show Rubek and Irene “whirled along with the masses of snow, and buried in them,” while Maia and her bear-hunter escape in safety to the plains. Interminable, and often very sage and penetrating, but always essentially rather maniacal, conversation fills up the texture of the play, which is certainly the least successful of Ibsen’s mature compositions. The boredom of Rubek in the midst of his eminence and wealth, and his conviction that by working in such concentration for the purity of art he merely wasted his physical life, inspire the portions of the play which bring most conviction and can be read with fullest satisfaction. It is obvious that such thoughts, such faint and unavailing regrets, pursued the old age of Ibsen; and the profound wound that his heart had received so long before at Gossensass was unhealed to his last moments of consciousness. An excellent French critic, M. P. G. La Chesnais, has ingeniously considered the finale of this play as a confession that Ibsen, at this end of his career, was convinced of the error of his earlier rigor, and, having ceased to believe in his mission, regretted the complete sacrifice of his life to his work. But perhaps it is not necessary to go into such subtleties.

When We Dead Awaken

is the production of a very tired old man, whose physical powers were declining.

In the year 1900, during our South African War, sentiment in the Scandinavian countries was very generally ranged on the side of the Boers. Ibsen, however, expressed himself strongly and publicly in favor of the English position. In an interview (November 24, 1900), which produced a considerable sensation, he remarked that the Boers were but half-cultivated, and had neither the will nor the power to advance the cause of civilization. Their sole object had come to be a jealous exclusion of all the higher forms of culture. The English were merely taking what the Boers themselves had stolen from an earlier race; the Boers had pitilessly hunted their precursors out of house and home, and now they were tasting the same cup themselves. These were considerations which had not occurred to generous sentimentalists in Norway, and Ibsen’s defence of England, which he supported in further communications with irony and courage, made a great sensation, and threw cold water on the pro-Boer sentimentalists. In Holland, where Ibsen had a wide public, this want of sympathy for Dutch prejudice raised a good deal of resentment, and Ibsen’s statements were replied to by the fiery young journalist, Cornelius Karel Elout, who even published a book on the subject. Ibsen took dignified notice of Elout’s attacks (December 9, 1900), repeating his defence of English policy, and this was the latest of his public appearances.

He took an interest, however, in the preparation of the great edition of his

Collected Works

, which appeared in Copenhagen in 1901 and

Kaempehöjen

,

Olaf Liljekrans

, both edited by Halvdan Koht, in 1902), of his

Correspondence

, edited by Koht and Julius Elias, in 1904, of the bibliographical edition of his collected works by Carl Naerup, in 1902, left him indifferent and scarcely conscious. The gathering darkness was broken, it is said, by a gleam of light in 1905; when the freedom of Norway and the accession of King Håkon were explained to him, he was able to express his joyful approval before the cloud finally sank upon his intelligence.

During his long illness Ibsen was troubled by aphasia, and he expressed himself painfully, now in broken Norwegian, now in still more broken German. His unhappy hero, Oswald Alving, in

Ghosts

, had thrilled the world by his cry, “Give me the sun, Mother!” and now Ibsen, with glassy eyes, gazed at the dim windows, murmuring “Keine Sonne, keine Sonne, keine Sonne!” At the table where all the works of his maturity had been written the old man sat, persistently learning and forgetting the alphabet. “Look!” he said to Julius Elias, pointing to his mournful pothooks, “See what I am doing! I am sitting here and learning my letters — my

letters

! I who was once a Writer!” Over this shattered image of what Ibsen had been, over this dying lion, who could not die, Mrs. Ibsen watched with the devotion of wife, mother and nurse in one, through six pathetic years. She was rewarded, in his happier moments, by the affection and tender gratitude of her invalid, whose latest articulate words were addressed to her—”

min söde, kjaere, snille frue

” (my sweet, dear, good wife); and she taught to adore their grandfather the three children of a new generation, Tankred, Irene, Eleonora.

Ibsen preserved the habit of walking about his room, or standing for hours staring out of window, until the beginning of May, 1906. Then a more complete decay confined him to his bed. After several days of unconsciousness, he died very peacefully in his house on Drammensvej, opposite the Royal Gardens of Christiania, at half-past two in the afternoon of May 23, 1906, being in his seventy-ninth year. By a unanimous vote of the he was awarded a public funeral, which the King of Norway attended in person, while King Edward VII was represented there by the British Minister. The event was regarded through out Norway as a national ceremony of the highest solemnity and importance, and the poet who had suffered such bitter humiliation and neglect in his youth was carried to his grave in solemn splendor, to the sound of a people’s lamentation.

CHAPTER IX. PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS

During the latest years of his life, which were spent as a wealthy and prosperous citizen of Christiania, the figure of Ibsen took forms of legendary celebrity which were equalled by no other living man of letters, not even by Tolstoi, and which had scarcely been surpassed, among the dead, by Victor Hugo. When we think of the obscurity of his youth and middle age, and of his consistent refusal to advertise himself by any of the little vulgar arts of self-exhibition, this extreme publicity is at first sight curious, but it can be explained. Norway is a small and a new country, inordinately, perhaps, but justly and gracefully proud of those — an Ole Bull, a Frithjof Nansen, an Edvard Grieg — who spread through the world evidences of its spiritual life. But the one who was more original, more powerful, more interesting than any other of her sons, had persistently kept aloof from the soil of Norway, and was at length recaptured and shut up in a golden cage with more expenditure of delicate labor than any perverse canary or escaped macaw had ever needed. Ibsen safely housed in Christiania! — it was the recovery of an important national asset, the resumption, after years of vexation and loss, of the intellectual regalia of Norway.

Ibsen, then — recaptured, though still in a frame of mind which left the captors nervous — was naturally an object of pride. For the benefit of the hundreds of tourists who annually pass through Christiania, it was more than tempting, it was irresistible to point out, in slow advance along Carl Johans Gade, in permanent silence at a table in the Grand Cafe, “our greatest citizen.” To this species of demonstration Ibsen unconsciously lent himself by his immobility, his regularity of habits, his solemn taciturnity. He had become more like a strange physical object than like a man among men. He was visible broadly and quietly, not conversing, rarely moving, quite isolated and self-contained, a recognized public spectacle, delivered up, as though bound hand and foot, to the kodak-hunter and the maker of “spicy” paragraphs. That Ibsen was never seen to do anything, or heard to say anything, that those who boasted of being intimate with him obviously lied in their teeth — all this prepared him for sacrifice. Christiania is a hot-bed of gossip, and its press one of the most “chatty” in the world. Our “greatest living author” was offered up as a wave-offering, and he smoked daily on the altar of the newspapers.

It will be extremely rash of the biographers of the future to try to follow Ibsen’s life day by day in the Christiania press from, let us say, 1891 to 1901. During that decade he occupied the reporters immensely, and he was particularly useful to the active young men who telegraph “chat” to Copenhagen, Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Berlin. Snapshots of Ibsen, dangerous illness of the playwright, quaint habits of the Norwegian dramatist, a poet’s double life, anecdotes of Ibsen and Mrs. —— , rumors of the King’s attitude to Ibsen — this pollenta, dressed a dozen ways, was the standing dish at every journalist’s table. If a space needed filling, a very rude reply to some fatuous question might be fitted in and called “Instance of Ibsen’s Wit.” The crop of fable was enormous, and always seemed to find a gratified public, for whom nothing was too absurd if it was supposed to illustrate “our great national poet.” Ibsen, meanwhile, did nothing at all. He never refuted a calumny, never corrected a story, but he threw an ironic glance through his gold- rimmed spectacles as he strolled down Carl Johan with his hands behind his back.

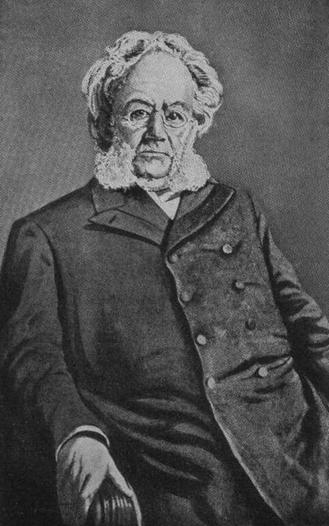

His personal appearance, it must be admitted, formed a tempting basis upon which to build a legend. His force of will had gradually transfigured his bodily forms until he thoroughly looked the part which he was expected to fill. At the age of thirty, to judge by the early photographs, he had been a commonplace-looking little man, with a shock of coal-black hair and a full beard, one of those hirsute types common in the Teutonic races, which may prove, on inquiry, to be painter, musician, or engraver, or possibly engineer, but less probably poet. Then came the exile from Norway, and the residence in Rome, marked by a little bust which stands before me now, where the beard is cut away into two round whiskers so as to release the firm round chin, and the long upper lip is clean-shaved. Here there is more liveliness, but still no distinction. Then comes a further advance — a photograph (in which I feel a tender pride, for it was made to please me) taken in Dresden (October 15, 1873), where the brow, perfectly smooth and white, has widened out, the whiskers have become less chubby, and the small, scrutinizing eyes absolutely sparkle with malice. Here, you say at last, is no poet, indeed, but an unusually cultivated banker or surprisingly adroit solicitor. Here the hair, retreating from the great forehead, begins to curl and roll with a distinguished wildness; here the long mouth, like a slit in the face, losing itself at each end in whisker, is a symbol of concentrated will power, a drawer in some bureau, containing treasures, firmly locked up.

Then came Munich, where Ibsen’s character underwent very considerable changes, or rather where its natural features became fixed and emphasized. We are not left without precious indication of his gestures and his looks at this time, when he was a little past the age of fifty. Where so much has been extravagantly written, or described in a journalistic key of false emphasis, great is the value of a quiet portrait by one of those who has studied Ibsen most intelligently. It is perhaps the most careful pen-sketch of him in any language.

Mr. William Archer, then, has given the following account of his first meeting with Ibsen. It was in the Scandinavia Club, in Rome, at the close of 1881: —

I had been about a quarter of an hour in the room, and was standing close to the door, when it opened, and in glided an undersized man with very broad shoulders and a large, leonine head, wearing a long black frock-coat with very broad lapels, on one of which a knot of red ribbon was conspicuous. I knew him at once, but was a little taken aback by his low stature. In spite of all the famous instances to the contrary, one instinctively associates greatness with size. His natural height was even somewhat diminished by a habit of bending forward slightly from the waist, begotten, no doubt, of short-sightedness, and the need to peer into things. He moved very slowly and noiselessly, with his hands behind his back — an unobtrusive personality, which would have been insignificant had the head been strictly proportionate to the rest of the frame. But there was nothing insignificant about the high and massive forehead, crowned with a mane of (then) iron-gray hair, the small and pale but piercing eyes behind the gold-rimmed spectacles, or the thin lipped mouth, depressed at the corners into a curve indicative of iron will, and set between bushy whiskers of the same dark gray as the hair. The most cursory observer could not but recognize power and character in the head; yet one would scarcely have guessed it to be the power of a poet, the character of a prophet. Misled, perhaps, by the ribbon at the buttonhole, and by an expression of reserve, almost of secretiveness, in the lines of the tight-shut mouth, one would rather have supposed one’s self face to face with an eminent statesman or diplomatist.

With the further advance of years all that was singular in Ibsen’s appearance became accentuated. The hair and beard turned snowy white; the former rose in a fierce sort of Oberland, the latter was kept square and full, crossing underneath the truculent chin that escaped from it. As Ibsen walked to a banquet in Christiania, he looked quite small under the blaze of crosses, stars and belts which he displayed when he unbuttoned the long black overcoat which enclosed him tightly. Never was he seen without his hands behind him, and the poet Holger Drachmann started a theory that as Ibsen could do nothing in the world but write, the Muse tied his wrists together at the small of his back whenever they were not actually engaged in composition. His regularity in all habits, his mechanical ways, were the subject of much amusement. He must sit day after day in the same chair, at the same table, in the same corner of the cafe, and woe to the ignorant intruder who was accidentally beforehand with him. No word was spoken, but the indignant poet stood at a distance, glaring, until the stranger should be pierced with embarrassment, and should rise and flee away.

Ibsen had the reputation of being dangerous and difficult of access. But the evidence of those who knew him best point to his having been phlegmatic rather than morose. He was “umbrageous,” ready to be discomposed by the action of others, but, if not vexed or startled, he was elaborately courteous. He had a great dislike of any abrupt movement, and if he was startled, he had the instinct of a wild animal, to bite. It was a pain to him to have the chain of his thoughts suddenly broken, and he could not bear to be addressed by chance acquaintances in street or café. When he was resident in Munich and Dresden, the difficulty of obtaining an interview with Ibsen was notorious. His wife protected him from strangers, and if her defences broke down, and the stranger contrived to penetrate the inner fastness, Ibsen might suddenly appear in the doorway, half in a rage, half quivering with distress, and say, in heartrending tones, “Bitte um Arbeitsruhe”—”Please let me work in peace!” They used to tell how in Munich a rich baron, who was the local Maecenas of letters, once bored Ibsen with a long recital of his love affairs, and ended by saying, with a wonderful air of fatuity, “To you, Master, I come, because of your unparalleled knowledge of the female heart. In your hands I place my fate. Advise me, and I will follow your advice.” Ibsen snapped his mouth and glared through his spectacles; then in a low voice of concentrated fury he said: “Get home, and — go to bed!” whereat his noble visitor withdrew, clothed with indignation as with a garment.

His voice was uniform, soft and quiet. The bitter things he said seemed the bitterer for his gentle way of saying them. As his shape grew burly and his head of hair enormous, the smallness of his extremities became accentuated. His little hands were always folded away as he tripped upon his tiny feet. His movements were slow and distrait. He wasted few words on the current incidents of life, and I was myself the witness, in 1899, of his

sang-froid

under distressing circumstances. Ibsen was descending a polished marble staircase when his feet slipped and he fell swiftly, precipitately, downward. He must have injured himself severely, he might have been killed, if two young gentlemen had not darted forward below and caught him in their arms. Once more set the right way up, Ibsen softly thanked his saviours with much frugality of phrase—”Tak, mine Herrer!” — tenderly touched an abraded surface of his top-hat, and marched forth homeward, unperturbed.

His silence had a curious effect on those in whose company he feasted; it seemed to hypnotise them. The great Danish actress, Mrs. Heiberg, herself the wittiest of talkers, said that to sit beside Ibsen was to peer into a gold-mine and not catch a glitter from the hidden treasure. But his dumbness was not so bitterly ironical as it was popularly supposed to be. It came largely from a very strange passivity which made definite action unwelcome to him. He could never be induced to pay visits, yet he would urge his wife and his son to accept invitations, and when they returned he would insist on being told every particular — who was there, what was said, even what everybody wore. He never went to a theatre or concert-room, except on the very rare occasions when he could be induced to be present at the performance of his own plays. But he was extremely fond of hearing about the stage. He had a memory for little things and an observation of trifles which was extraordinary. He thought it amazing that people could go into a room and not notice the pattern of the carpet, the color of the curtains, the objects on the walls; these being details which he could not help observing and retaining. This trait comes out in his copious and minute stage directions.

Ibsen was simplicity itself; no man was ever less affected. But his character was closed; he was perpetually on the defensive. He was seldom confidential, he never “gave way”; his emotions and his affections were genuine, but his heart was a fenced city. He had little sense of domestic comfort; his rooms were bare and neat, with no personal objects save those which belonged to his wife. Even in the days of his wealth, in the fine house on Drammensvej, there was a singular absence of individuality about his dwelling rooms. They might have been prepared for a rich American traveller in some hotel. Through a large portion of his career in Germany he lived in furnished rooms, not because he did not possess furniture of his own, which was stored up, but because he paid no sort of homage to his own penates. He had friends, but he did not cultivate them; he rather permitted them, at intervals, to cultivate him. To Georg Brandes (March 6, 1870) he wrote: “Friends are a costly luxury; and when one has devoted one’s self wholly to a profession and a mission here in life, there is no place left for friends.” The very charming story of Ibsen’s throwing his arms round old Hans Christian Andersen’s neck, and forcing him to be genial and amiable, [Note:

Samliv med Ibsen.

] is not inconsistent with the general rule of passivity and shyness which he preserved in matters of friendship.

Ibsen’s reading was singularly limited. In his fine rooms on Drammensvej I remember being struck by seeing no books at all, except the large Bible which always lay at his side, and formed his constant study. He disliked having his partiality for the Bible commented on, and if, as would sometimes be the case, religious people expressed pleasure at finding him deep in the sacred volume, Ibsen would roughly reply: “It is only for the sake of the language.” He was the enemy of anything which seemed to approach cant and pretension, and he concealed his own views as closely as he desired to understand the views of others. He possessed very little knowledge of literature. The French he despised and repudiated, although he certainly had studied Voltaire with advantage; of the Italians he knew only Dante and of the English only Shakespeare, both of whom he had studied in translations. In Danish he read and reread Holberg, who throughout his life unquestionably remained Ibsen’s favorite author; he preserved a certain admiration for the Danish classics of his youth: Heiberg, Hertz, Schack-Steffelt. In German, the foreign language which he read most currently, he was strangely ignorant of Schiller and Heine, and hostile to Goethe, although

Brand

and

Peer Gynt

must owe something of their form to

Faust

. But the German poets whom he really enjoyed were two dramatists of the age preceding his own, Otto Ludwig (1813-65) and Friedrich Hebbel (1813-63). Each of these playwrights had been occupied in making certain reforms, of a realistic tendency, in the existing tradition of the stage, and each of them dealt, before any one else in Europe did so, with “problems” on the stage. These two German poets, but Hebbel particularly, passed from romanticism to realism, and so on to mysticism, in a manner fascinating to Ibsen, whom it is possible that they influenced. [Note: It would be interesting to compare

Die Niebelungen

, the trilogy which Hebbel published in

Emperor and Galilean

.] He remained, in later years, persistently ignorant of Zola, and of Tolstoi he had read, with contemptuous disapproval, only some of the polemical pamphlets. He said to me, in 1899, of the great Russian: “Tolstoi? — he is mad!” with a screwing up of the features such as a child makes at the thought of a black draught.