Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (2280 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

That letter sketched for me the story of his travel through France, and I may at once say that I thus received, from week to week, the “first sprightly runnings” of every description in his

Pictures from Italy

. But my rule as to the American letters must be here observed yet more strictly; and nothing resembling his printed book, however distantly, can be admitted into these pages. Even so my difficulty of rejection will not be less; for as he had not actually decided, until the very last, to publish his present experiences at all, a larger number of the letters were left unrifled by him. He had no settled plan from the first, as in the other case.

His most valued acquaintance at Albaro was the French consul-general, a student of our literature who had written on his books in one of the French reviews, and who with his English wife lived in the very next villa, though so oddly shut away by its vineyard that to get from the one adjoining house to the other was a mile’s journey.

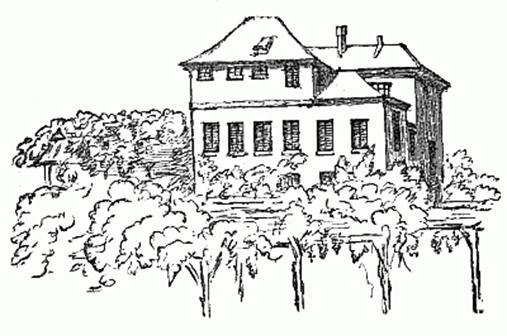

Describing, in that August letter, his first call from this new friend thus pleasantly self-recommended, he makes the visit his excuse for breaking off from a facetious description of French inns to introduce to me a sketch, from a pencil outline by Fletcher, of what bore the imposing name of the Villa di Bella vista, but which he called by the homelier one of its proprietor, Bagnerello. “This, my friend, is quite accurate. Allow me to explain it. You are standing, sir, in our vineyard, among the grapes and figs. The Mediterranean is at your back as you look at the house: of which two sides, out of four, are here depicted. The lower story (nearly concealed by the vines) consists of the hall, a wine-cellar, and some store-rooms. The three windows on the left of the first floor belong to the sala, lofty and whitewashed, which has two more windows round the corner. The fourth window

did

belong to the dining-room, but I have changed one of the nurseries for better air; and it now appertains to that branch of the establishment. The fifth and sixth, or two right-hand windows, sir, admit the light to the inimitable’s (and uxor’s) chamber; to which the first window round the right-hand corner, which you perceive in shadow, also belongs. The next window in shadow, young sir, is the bower of Miss H. The next, a nursery window; the same having two more round the corner again. The bowery-looking place stretching out upon the left of the house is the terrace, which opens out from a French window in the drawing-room on the same floor, of which you see nothing: and forms one side of the court-yard. The upper windows belong to some of those uncounted chambers upstairs; the fourth one, longer than the rest, being in F.’s bedroom. There is a kitchen or two up there besides, and my dressing-room; which you can’t see from this point of view. The kitchens and other offices in use are down below, under that part of the house where the roof is longest. On your left, beyond the bay of Genoa, about two miles off, the Alps stretch off into the far horizon; on your right, at three or four miles distance, are mountains crowned with forts. The intervening space on both sides is dotted with villas, some green, some red, some yellow, some blue, some (and ours among the number) pink. At your back, as I have said, sir, is the ocean; with the slim Italian tower of the ruined church of St. John the Baptist rising up before it, on the top of a pile of savage rocks. You go through the court-yard, and out at the gate, and down a narrow lane to the sea. Note. The sala goes sheer up to the top of the house; the ceiling being conical, and the little bedrooms built round the spring of its arch. You will observe that we make no pretension to architectural magnificence, but that we have abundance of room. And here I am, beholding only vines and the sea for days together. . . . Good Heavens! How I wish you’d come for a week or two, and taste the white wine at a penny farthing the pint. It is excellent.” . . . Then, after seven days: “I have got my paper and inkstand and figures now (the box from Osnaburgh-terrace only came last Thursday), and can think — I have begun to do so every morning — with a business-like air, of the Christmas book. My paper is arranged, and my pens are spread out in the usual form. I think you know the form — Don’t you? My books have not passed the custom-house yet, and I tremble for some volumes of Voltaire. . . . I write in the best bedroom. The sun is off the corner window at the side of the house by a very little after twelve; and I can then throw the blinds open, and look up from my paper, at the sea, the mountains, the washed-out villas, the vineyards, at the blistering white hot fort with a sentry on the drawbridge standing in a bit of shadow no broader than his own musket, and at the sky, as often as I like. It is a very peaceful view, and yet a very cheerful one. Quiet as quiet can be.”

Not yet however had the time for writing come. A sharp attack of illness befell his youngest little daughter, Kate, and troubled him much. Then, after beginning the Italian grammar himself, he had to call in the help of a master; and this learning of the language took up time. But he had an aptitude for it, and after a month’s application told me (24th of August) that he could ask in Italian for whatever he wanted in any shop or coffee-house, and could read it pretty well. “I wish you could see me” (16th of September), “without my knowing it, walking about alone here. I am now as bold as a lion in the streets. The audacity with which one begins to speak when there is no help for it, is quite astonishing.” The blank impossibility at the outset, however, of getting native meanings conveyed to his English servants, he very humorously described to me; and said the spell was first broken by the cook, “being really a clever woman, and not entrenching herself in that astonishing pride of ignorance which induces the rest to oppose themselves to the receipt of any information through any channel, and which made A. careless of looking out of window, in America, even to see the Falls of Niagara.” So that he soon had to report the gain, to all of them, from the fact of this enterprising woman having so primed herself with “the names of all sorts of vegetables, meats, soups, fruits, and kitchen necessaries,” that she was able to order whatever was needful of the peasantry that were trotting in and out all day, basketed and barefooted. Her example became at once contagious;

and before the end of the second week of September news reached me that “the servants are beginning to pick up scraps of Italian; some of them go to a weekly conversazione of servants at the Governor’s every Sunday night, having got over their consternation at the frequent introduction of quadrilles on these occasions; and I think they begin to like their foreigneering life.”

In the tradespeople they dealt with at Albaro he found amusing points of character. Sharp as they were after money, their idleness quenched even that propensity. Order for immediate delivery two or three pounds of tea, and the tea-dealer would be wretched. “Won’t it do to-morrow?” “I want it now,” you would reply; and he would say, “No, no, there can be no hurry!” He remonstrated against the cruelty. But everywhere there was deference, courtesy, more than civility. “In a café a little tumbler of ice costs something less than threepence, and if you give the waiter in addition what you would not offer to an English beggar, say, the third of a halfpenny, he is profoundly grateful.” The attentions received from English residents were unremitting.

In moments of need at the outset, they bestirred themselves (“large merchants and grave men”) as if they were the family’s salaried purveyors; and there was in especial one gentleman named Curry whose untiring kindness was long remembered.

The light, eager, active figure soon made itself familiar in the streets of Genoa, and he never went into them without bringing some oddity away. I soon heard of the strada Nuova and strada Balbi; of the broadest of the two as narrower than Albany-street, and of the other as less wide than Drury-lane or Wych-street; but both filled with palaces of noble architecture and of such vast dimensions that as many windows as there are days in the year might be counted in one of them, and this not covering by any means the largest plot of ground. I heard too of the other streets, none with footways, and all varying in degrees of narrowness, but for the most part like Field-lane in Holborn, with little breathing-places like St. Martin’s-court; and the widest only in parts wide enough to enable a carriage and pair to turn. “Imagine yourself looking down a street of Reform Clubs cramped after this odd fashion, the lofty roofs almost seeming to meet in the perspective.” In the churches nothing struck him so much as the profusion of trash and tinsel in them that contrasted with their real splendours of embellishment. One only, that of the Cappucini friars, blazed every inch of it with gold, precious stones, and paintings of priceless art; the principal contrast to its radiance being the dirt of its masters, whose bare legs, corded waists, and coarse brown serge never changed by night or day, proclaimed amid their corporate wealth their personal vows of poverty. He found them less pleasant to meet and look at than the country people of their suburb on festa-days, with the Indulgences that gave them the right to make merry stuck in their hats like turnpike-tickets. He did not think the peasant girls in general good-looking, though they carried themselves daintily and walked remarkably well: but the ugliness of the old women, begotten of hard work and a burning sun, with porters’ knots of coarse grey hair grubbed up over wrinkled and cadaverous faces, he thought quite stupendous. He was never in a street a hundred yards long without getting up perfectly the witch part of

Macbeth

.

With the theatres of course he soon became acquainted, and of that of the puppets he wrote to me again and again with humorous rapture. “There are other things,” he added, after giving me the account which is published in his book, “too solemnly surprising to dwell upon. They must be seen. They must be seen. The enchanter carrying off the bride is not greater than his men brandishing fiery torches and dropping their lighted spirits of wine at every shake. Also the enchanter himself, when, hunted down and overcome, he leaps into the rolling sea, and finds a watery grave. Also the second comic man, aged about 55 and like George the Third in the face, when he gives out the play for the next night. They must all be seen. They can’t be told about. Quite impossible.” The living performers he did not think so good, a disbelief in Italian actors having been always a heresy with him, and the deplorable length of dialogue to the small amount of action in their plays making them sadly tiresome. The first that he saw at the principal theatre was a version of Balzac’s

Père Goriot

. “The domestic Lear I thought at first was going to be very clever. But he was too pitiful — perhaps the Italian reality would be. He was immensely applauded, though.” He afterwards saw a version of Dumas’ preposterous play of

Kean

, in which most of the representatives of English actors wore red hats with steeple crowns, and very loose blouses with broad belts and buckles round their waists. “There was a mysterious person called the Prince of Var-lees” (Wales), “the youngest and slimmest man in the company, whose badinage in Kean’s dressing-room was irresistible; and the dresser wore top-boots, a Greek skull-cap, a black velvet jacket, and leather breeches. One or two of the actors looked very hard at me to see how I was touched by these English peculiarities — especially when Kean kissed his male friends on both cheeks.” The arrangements of the house, which he described as larger than Drury-lane, he thought excellent. Instead of a ticket for the private box he had taken on the first tier, he received the usual key for admission which let him in as if he lived there; and for the whole set-out, “quite as comfortable and private as a box at our opera,” paid only eight and fourpence English. The opera itself had not its regular performers until after Christmas, but in the summer there was a good comic company, and he saw the

Scaramuccia

and the

Barber of Seville

brightly and pleasantly done. There was also a day theatre, beginning at half past four in the afternoon; but beyond the novelty of looking on at the covered stage as he sat in the fresh pleasant air, he did not find much amusement in the Goldoni comedy put before him. There came later a Russian circus, which the unusual rains of that summer prematurely extinguished.

The Religious Houses he made early and many enquiries about, and there was one that had stirred and baffled his curiosity much before he discovered what it really was. All that was visible from the street was a great high wall, apparently quite alone, no thicker than a party wall, with grated windows, to which iron screens gave farther protection. At first he supposed there had been a fire; but by degrees came to know that on the other side were galleries, one above another, one above another, and nuns always pacing them to and fro. Like the wall of a racket-ground outside, it was inside a very large nunnery; and let the poor sisters walk never so much, neither they nor the passers-by could see anything of each other. It was close upon the Acqua Sola, too; a little park with still young but very pretty trees, and fresh and cheerful fountains, which the Genoese made their Sunday promenade; and underneath which was an archway with great public tanks, where, at all ordinary times, washerwomen were washing away, thirty or forty together. At Albaro they were worse off in this matter: the clothes there being washed in a pond, beaten with gourds, and whitened with a preparation of lime: “so that,” he wrote to me (24th of August), “what between the beating and the burning they fall into holes unexpectedly, and my white trowsers, after six weeks’ washing, would make very good fishing-nets. It is such a serious damage that when we get into the Peschiere we mean to wash at home.”