Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (2285 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

Of the help his courier continued to be to him I had whimsical instances in almost every letter, but he appears too often in the published book to require such celebration here. He is however an essential figure to two little scenes sketched for me at Lodi, and I may preface them by saying that Louis Roche, a native of Avignon, justified to the close his master’s high opinion. He was again engaged for nearly a year in Switzerland, and soon after, poor fellow, though with a jovial robustness of look and breadth of chest that promised unusual length of days, was killed by heart-disease. “The brave C continues to be a prodigy. He puts out my clothes at every inn as if I were going to stay there twelve months; calls me to the instant every morning; lights the fire before I get up; gets hold of roast fowls and produces them in coaches at a distance from all other help, in hungry moments; and is invaluable to me. He is such a good fellow, too, that little rewards don’t spoil him. I always give him, after I have dined, a tumbler of Sauterne or Hermitage or whatever I may have; sometimes (as yesterday) when we have come to a public-house at about eleven o’clock, very cold, having started before day-break and had nothing, I make him take his breakfast with me; and this renders him only more anxious than ever, by redoubling attentions, to show me that he thinks he has got a good master . . . I didn’t tell you that the day before I left Genoa, we had a dinner-party — our English consul and his wife; the banker; Sir George Crawford and his wife; the De la Rues; Mr. Curry; and some others, fourteen in all. At about nine in the morning, two men in immense paper caps enquired at the door for the brave C, who presently introduced them in triumph as the Governor’s cooks, his private friends, who had come to dress the dinner! Jane wouldn’t stand this, however; so we were obliged to decline. Then there came, at half-hourly intervals, six gentlemen having the appearance of English clergymen; other private friends who had come to wait. . . . We accepted

their

services; and you never saw anything so nicely and quietly done. He had asked, as a special distinction, to be allowed the supreme control of the dessert; and he had ices made like fruit, had pieces of crockery turned upside down so as to look like other pieces of crockery non-existent in this part of Europe, and carried a case of tooth-picks in his pocket. Then his delight was, to get behind Kate at one end of the table, to look at me at the other, and to say to Georgy in a low voice whenever he handed her anything, ‘What does master think of datter ‘rangement? Is he content?’ . . . If you could see what these fellows of couriers are when their families are not upon the move, you would feel what a prize he is. I can’t make out whether he was ever a smuggler, but nothing will induce him to give the custom-house-officers anything: in consequence of which that portmanteau of mine has been unnecessarily opened twenty times. Two of them will come to the coach-door, at the gate of a town. ‘Is there anything contraband in this carriage, signore?’ — ’No, no. There’s nothing here. I am an Englishman, and this is my servant.’ ‘A buono mano signore?’ ‘Roche,’(in English) ‘give him something, and get rid of him.’ He sits unmoved. ‘A buono mano signore?’ ‘Go along with you!’ says the brave C. ‘Signore, I am a custom-house-officer!’ ‘Well, then, more shame for you!’ — he always makes the same answer. And then he turns to me and says in English: while the custom-house-officer’s face is a portrait of anguish framed in the coach-window, from his intense desire to know what is being told to his disparagement: ‘Datter chip,’ shaking his fist at him, ‘is greatest tief — and you know it you rascal — as never did en-razh me so, that I cannot bear myself!’ I suppose chip to mean chap, but it may include the custom-house-officer’s father and have some reference to the old block, for anything I distinctly know.”

He closed his Lodi letter next day at Milan, whither his wife and her sister had made an eighty miles journey from Genoa, to pass a couple of days with him in Prospero’s old Dukedom before he left for London. “We shall go our several ways on Thursday morning, and I am still bent on appearing at Cuttris’s on Sunday the first, as if I had walked thither from Devonshire-terrace. In the meantime I shall not write to you again . . . to enhance the pleasure (if anything

can

enhance the pleasure) of our meeting . . . I am opening my arms so wide!” One more letter I had nevertheless; written at Strasburg on Monday night the 25th; to tell me I might look for him one day earlier, so rapid had been his progress. He had been in bed only once, at Friburg for two or three hours, since he left Milan; and he had sledged through the snow on the top of the Simplon in the midst of prodigious cold. “I am sitting here

in

a wood-fire, and drinking brandy and water scalding hot, with a faint idea of coming warm in time. My face is at present tingling with the frost and wind, as I suppose the cymbals may, when that turbaned turk attached to the life guards’ band has been newly clashing at them in St. James’s-park. I am in hopes it may be the preliminary agony of returning animation.”

AT

AT

LINCOLN’S-INN-FIELDS, MONDAY THE ND OF DECEMBER .

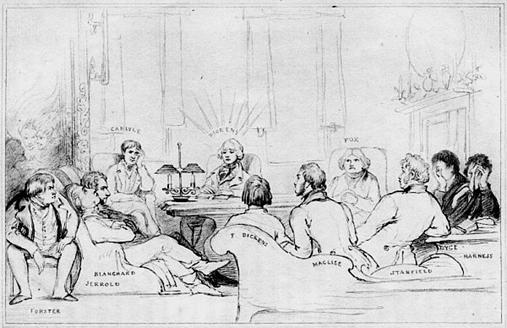

There was certainly no want of animation when we met. I have but to write the words to bring back the eager face and figure, as they flashed upon me so suddenly this wintry Saturday night that almost before I could be conscious of his presence I felt the grasp of his hand. It is almost all I find it possible to remember of the brief, bright, meeting. Hardly did he seem to have come when he was gone. But all that the visit proposed he accomplished. He saw his little book in its final form for publication; and, to a select few brought together on Monday the 2nd of December at my house, had the opportunity of reading it aloud. An occasion rather memorable, in which was the germ of those readings to larger audiences by which, as much as by his books, the world knew him in his later life; but of which no detail beyond the fact remains in my memory, and all are now dead who were present at it excepting only Mr. Carlyle and myself. Among those however who have thus passed away was one, our excellent Maclise, who, anticipating the advice of Captain Cuttle, had “made a note of” it in pencil, which I am able here to reproduce. It will tell the reader all he can wish to know. He will see of whom the party consisted; and may be assured (with allowance for a touch of caricature to which I may claim to be considered myself as the chief victim), that in the grave attention of Carlyle, the eager interest of Stanfield and Maclise, the keen look of poor Laman Blanchard, Fox’s rapt solemnity, Jerrold’s skyward gaze, and the tears of Harness and Dyce, the characteristic points of the scene are sufficiently rendered. All other recollection of it is passed and gone; but that at least its principal actor was made glad and grateful, sufficient farther testimony survives. Such was the report made of it, that once more, on the pressing intercession of our friend Thomas Ingoldsby (Mr. Barham), there was a second reading to which the presence and enjoyment of Fonblanque gave new zest;

and when I expressed to Dickens, after he left us, my grief that he had had so tempestuous a journey for such brief enjoyment, he replied that the visit had been one happiness and delight to him. “I would not recall an inch of the way to or from you, if it had been twenty times as long and twenty thousand times as wintry. It was worth any travel — anything! With the soil of the road in the very grain of my cheeks, I swear I wouldn’t have missed that week, that first night of our meeting, that one evening of the reading at your rooms, aye, and the second reading too, for any easily stated or conceived consideration.”

He wrote from Paris, at which he had stopped on his way back to see Macready, whom an engagement to act there with Mr. Mitchell’s English company had prevented from joining us in Lincoln’s-inn-fields. There had been no such frost and snow since 1829, and he gave dismal report of the city. With Macready he had gone two nights before to the Odéon to see Alexandre Dumas’

Christine

played by Madame St. George, “once Napoleon’s mistress; now of an immense size, from dropsy I suppose; and with little weak legs which she can’t stand upon. Her age, withal, somewhere about 80 or 90. I never in my life beheld such a sight. Every stage-conventionality she ever picked up (and she has them all) has got the dropsy too, and is swollen and bloated hideously. The other actors never looked at one another, but delivered all their dialogues to the pit, in a manner so egregiously unnatural and preposterous that I couldn’t make up my mind whether to take it as a joke or an outrage.” And then came allusion to a project we had started on the night of the reading, that a private play should be got up by us on his return from Italy. “You and I, sir, will reform this altogether.” He had but to wait another night, however, when he saw it all reformed at the Italian opera where Grisi was singing in

Il Pirato

, and “the passion and fire of a scene between her, Mario, and Fornasari, was as good and great as it is possible for anything operatic to be. They drew on one another, the two men — not like stage-players, but like Macready himself: and she, rushing in between them; now clinging to this one, now to that, now making a sheath for their naked swords with her arms, now tearing her hair in distraction as they broke away from her and plunged again at each other; was prodigious.” This was the theatre at which Macready was immediately to act, and where Dickens saw him next day rehearse the scene before the doge and council in

Othello

, “not as usual facing the float but arranged on one side,” with an effect that seemed to him to heighten the reality of the scene.

He left Paris on the night of the 13th with the malle poste, which did not reach Marseilles till fifteen hours behind its time, after three days and three nights travelling over horrible roads. Then, in a confusion between the two rival packets for Genoa, he unwillingly detained one of them more than an hour from sailing; and only managed at last to get to her just as she was moving out of harbour. As he went up the side, he saw a strange sensation among the angry travellers whom he had detained so long; heard a voice exclaim “I am blarmed if it ain’t Dickens!” and stood in the centre of a group of

Five Americans!

But the pleasantest part of the story is that they were, one and all, glad to see him; that their chief man, or leader, who had met him in New York, at once introduced them all round with the remark, “Personally our countrymen, and you, can fix it friendly sir, I do expectuate;” and that, through the stormy passage to Genoa which followed, they were excellent friends. For the greater part of the time, it is true, Dickens had to keep to his cabin; but he contrived to get enjoyment out of them nevertheless. The member of the party who had the travelling dictionary wouldn’t part with it, though he was dead sick in the cabin next to my friend’s; and every now and then Dickens was conscious of his fellow-travellers coming down to him, crying out in varied tones of anxious bewilderment, “I say, what’s French for a pillow?” “Is there any Italian phrase for a lump of sugar? Just look, will you?” “What the devil does echo mean? The garsong says echo to everything!” They were excessively curious to know, too, the population of every little town on the Cornice, and all its statistics; “perhaps the very last subjects within the capacity of the human intellect,” remarks Dickens, “that would ever present themselves to an Italian steward’s mind. He was a very willing fellow, our steward; and, having some vague idea that they would like a large number, said at hazard fifty thousand, ninety thousand, four hundred thousand, when they asked about the population of a place not larger than Lincoln’s-inn-fields. And when they said

Non Possible!

(which was the leader’s invariable reply), he doubled or trebled the amount; to meet what he supposed to be their views, and make it quite satisfactory.”

LAST MONTHS IN ITALY.

1845.

Jesuit Interferences — Travel Southward — Carrara and Pisa — A Wild Journey — At Radicofani — A Beggar and his Staff — At Rome — Terracina — Bay of Naples — Lazzaroni — Sad English News — At Florence — Visit to Landor’s Villa — At Lord Holland’s — Return to Genoa — Italy’s Best Season — A Funeral — Nautical Incident — Fireflies at Night — Returning by Switzerland — At Lucerne — Passage of the St. Gothard — Splendour of Swiss Scenery — Swiss Villages.

On the 22nd of December he had resumed his ordinary Genoa life; and of a letter from Jeffrey, to whom he had dedicated his little book, he wrote as “most energetic and enthusiastic. Filer sticks in his throat rather, but all the rest is quivering in his heart. He is very much struck by the management of Lilian’s story, and cannot help speaking of that; writing of it all indeed with the freshness and ardour of youth, and not like a man whose blue and yellow has turned grey.” Some of its words have been already given. “Miss Coutts has sent Charley, with the best of letters to me, a Twelfth Cake weighing ninety pounds, magnificently decorated; and only think of the characters, Fairburn’s Twelfth Night characters, being detained at the custom-house for Jesuitical surveillance! But these fellows are —

— Well! never mind. Perhaps you have seen the history of the Dutch minister at Turin, and of the spiriting away of his daughter by the Jesuits? It is all true; though, like the history of our friend’s servant,

almost incredible. But their devilry is such that I am assured by our consul that if, while we are in the south, we were to let our children go out with servants on whom we could not implicitly rely, these holy men would trot even their small feet into churches with a view to their ultimate conversion! It is tremendous even to see them in the streets, or slinking about this garden.” Of his purpose to start for the south of Italy in the middle of January, taking his wife with him, his letter the following week told me; dwelling on all he had missed, in that first Italian Christmas, of our old enjoyments of the season in England; and closing its pleasant talk with a postscript at midnight. “First of January, 1845. Many many many happy returns of the day! A life of happy years! The Baby is dressed in thunder, lightning, rain, and wind. His birth is most portentous here.”