Constant Touch (17 page)

Authors: Jon Agar

Tags: #science, #engineering and technology, #telecommunications, #electronics and communications, #telephone and wireless technology, #internet, #mobile telephones

The BART episode is a curious one. The denial of a cellphone service â the temporary blackout â is a tool of authorities, but a blunt one. Similar examples can be found across the world. Just after the London 7/7 bombings in 2005, the cellphone service in four of Manhattan's tunnels â Holland, Lincoln, Midtown and Battery â was switched off for several days. In the same year in Thailand, where the government was facing an insurgency in the Muslim-majority south of the country, unregistered prepaid phones were disconnected. Again the concern was terrorism, specifically the use of phones as triggers. India did the same to millions in 2009, as we have seen. In the Madrid train bombing of 2004, mobile phones were used as timers to trigger the bomb â essentially using the phone as a clock rather than as a communication device.

So we have seen examples of many different kinds of âoases of quiet', from single rooms to whole buildings, tunnels and railway tracks. But what about whole countries? Until recently, only government officials or people working for foreign firms could purchase a mobile phone in Cuba. In April 2008, Raul Castro, the new president of the country and younger brother of Fidel, lifted the restrictions. Crowds gathered at shop windows

on the first day. Within ten days, 7,400 new mobile subscriptions had been made through the state telecoms firm, Etecsa. In reaction, scenting an opening, the United States allowed relatives to send mobile phones by post to the communist island. Usage in Cuba remains low, however: a consequence of poverty now rather than prohibition.

And there will always be people who do not want a mobile phone. They will preserve their own oasis of quiet, and quite rightly so. One personal response springs to mind. It is a vox pop comment to a BBC News feature on the iPhone: the words of Tracy Churchill, from Ely in the Cambridgeshire fenland:

iThis and iThat ... What is happening to the world? Have we lost the art of entertaining ourselves without digital gadgets? I am proud to say I do not own a mobile, let alone one with camera, internet access and a million other things that cost people money, but don't use. If someone wants to speak to me they can use my landline, or write me a letter ... old-fashioned maybe, but at least I'm not permanently attached to an inanimate object isolating me from the wonderful natural world around us.

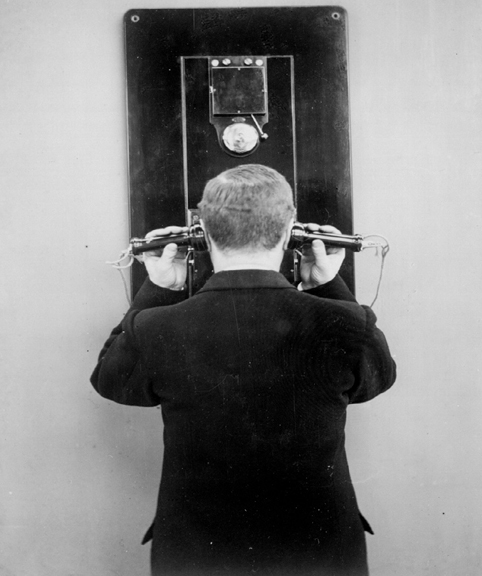

Perpetuum mobile

?

(BT Archives)

By

2002 there were at least a billion cellular subscribers in the world. By 2012 there were six, including a billion smartphones alone. The mobile cellular phone has meant different things to different people: a way of rebuilding economies in eastern Europe, an instrument of

unification in western Europe, a fashion statement in Finland or Japan, a mundane means of communication in the United States, or an agent of political change in the Philippines. Different nations made different mobiles.

But, through all the contrasting national pictures of cellular use, a common pattern can be glimpsed: there has been a correlation, a sympathetic alignment, between the mobile phone and the horizontal social networks that have grown in the last few decades in comparison with older, more hierarchical, more centralised models of organisation. There is, I feel, a profound sense in which the mobile represents, activates, and is activated by these networks in the way that, say, the mainframe computer of the 1950s gave form to the centralised, hierarchical, bureaucratic organisation. What changed between then and now was a social revolution â of which technological change was part and parcel. The critical attitude towards centralised authority that emerged in the 1960s can be seen in examples as diverse as the CB radio fad of the early 1970s, with its alternative jargon and myths of living outside traditional society, or the use of mobile phones to organise illegal rave parties around London's M25 motorway in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Social revolution produced the youth movement that in turn demanded a material culture â including cellphones â that would meet young people's social needs of

distinct

fashions,

and

independent

means of communication between friends.

We must be careful not to suggest that technologies of mobility inevitably oppose centralised power. Just over 2,000 years ago, city-states around Italy and the Mediterranean began to feel the force of a new power: imperial Rome. These city-states came to accept â and see â themselves as âRoman' partly because âRoman' roads gave the social elite an effective means of travel. Anywhere visible from the road became somewhere from which this association of mobility, the technologies enabling mobility, and centralised Roman power could be reinforced. The great triumphal arches, adverts for âRome' through which a traveller had to pass, provide one example. As political power became concentrated in the hands first of an oligarchy and senate, and then of individual emperors, so the road system became ever more important. Technological systems of mobility helped create the Roman world, and mobility reinforced central, hierarchical, imperial power.

But try a historical thought experiment: what would Rome have been like if the technologies of mobility had been truly demotic? If, instead of being built to create and sustain the mobility of a social elite, the roads and road culture of Rome had been for the people? Well, I would suggest as a parallel that the mobile phone as it became in the last decade of the 20th century, and the car by mid-century, are just such demotic â and

interconnected â technologies of mobility. GSM, the âmost complicated system built by man since the Tower of Babel', was meant to make âEuropeans' as the roads made âRomans', but it was not dedicated to the maintenance of a privileged elite. (However, in other ways the comparison stands. The power of several mobile-based multinationals is becoming imperial in stature, and operator portals, which advertise the riches of such companies and through which we must pass, bear more than a passing resemblance to triumphal arches.)

There are fierce tensions between demotic technologies of mobility and centralised power. I've given many throughout this book, but the thought of Rome prompts one more example. In March 2001, the Italian Bishops' Conference, the governing organisation of the Roman Catholic Church in that country, circulated to all parish priests a strongly worded warning not to allow mobile aerial masts on church buildings. The mobile operators were in desperate need of sites for new masts, preferably high up and in the centres of populations, and were willing to pay handsomely. The parish priest, often some distance from the riches of the Vatican, had an expensive church to maintain and falling congregations. While some very worldly concerns fell against the obvious deal â such as legal violations that might endanger churches' tax-exempt status â a greater danger arose: the centrality of Christian

symbols would be blurred if the spires also advertised mobile masts. The masts, wrote the bishops, were âalien to the sanctity' of churches. And in a world where the Catholic church, perhaps the prime model of authority and hierarchy, perceived numerous threats, the blurring of symbols of mobility and static power was unconscionable. (Broadcasting, always at ease with hierarchy, was another matter: Vatican Radio was permitted its masts.) In contrast, the more compromising, more pragmatic or less symbolically minded Church of England signed a deal with Quintel S4, a spin-off of QinetiQ (the commercial arm of Britain's defence research agency) in June 2002 to allow mobile masts on 16,000 churches.

But if compromises can be made with hierarchies, the demotic mobile has been found to fit within horizontal social networks with greater ease. This was not discovered by the mobile phone manufacturing or operating companies (although companies such as Nokia can boast a flattened management structure, and espouse a pro-innovation, anti-deferential corporate philosophy). Instead, the demotic mobile was the discovery, and reflection, of the users. No one within the industry, for example, expected the extent of the success of Short Message Service (SMS). Indeed, even now it is remarkable that a service that works out on average at roughly a penny or cent

per character

was successful at all. But the power of text, like many other aspects

of the mobile, was found by the people who used it, not the people who planned it.

The mobile phone in the early 21st century is in a moment of transition. The third generation has been launched and a fourth is being rolled out; there are rival models of wireless communication, some centralised (like the satellite system Globalstar), some even more potentially demotic (wireless LAN, Bluetooth and a host of other means of passing data from device to device free of charge). The mobile â as a phone â is in danger on three fronts: technological change might add to it so many new features, benefiting from greater data-handling capacities, that it might barely act like a phone. Its own flexibility would destroy it, or transform it into something else. The mobile phone would have been a mere passing stage to another technology. Perhaps some rival means of mobile communication and data handling across ad hoc

networks will prove more economical, more popular or a better fit for social or political imperatives. The mobile cellular standards will lie abandoned. The immense sums spent on outmoded or unwanted 3G and 4G licences will collapse some of the biggest corporations, with significant effects on the rest of the economy. There is real nervousness that the new mobile might be rejected by a more powerful force, the users. Certainly patterns of use are changing as the smartphone displaces the older cellphone. The number of âcalls', for example, actually fell for the first time in

Britain in 2011, as voice communication becomes less central. âTeenagers and young adults are leading these changes in communication habits, increasingly socialising with friends and family online and through text messages despite saying they prefer to talk face to face,' concluded Ofcom, Britain's regulator watchdog.

But there is good reason to suggest that users will continue to love the mobile phone. Back in 1906, the inventor of electronic circuitry, Lee de Forest, made the first radio transmission to an automobile. A press release issued to advertise the achievement expressed de Forest's hope that in the near future âit will be possible for businessmen, even while automobiling, to be kept in constant touch'. In the centralised, hierarchical world of Ford, such a dream made little sense. While it was technically possible earlier, the cellular mobile phone only took off after the 1960s. By then there had been a sea change in both politics and technology, one affecting the other; after which, to put it crudely, networks of people have prospered and hierarchical styles have suffered. When I smashed up my mobile phone I wanted to find out what was in it and in what sort of world it made sense to assemble it. Apart, the debris reflected a fragmented, flexible, atomised world. Put together, the mobile provides a

network

, giving society back a cohesion of sorts. We've seen that the phone can be assembled in many ways. But only after the great transformation of social attitudes that took place in the

1960s could a world

wish

to be in constant touch. We live

this

side of that transformation, which is why the mobile will be, if not perpetually in motion, at least moving for some time yet.

And great claims are made about such a world. With the first and second generation of mobile phones, constant touch meant constant communicative contact. With smartphones, constant touch means this and more: stroking screens, moving data and keeping in contact via social media. âMobile communication has arguably had a bigger impact on humankind in a shorter period of time than any other invention in human history,' suggested the authors of

Maximising Mobile

, a World Bank report on the opportunities offered for development. They quote, approvingly, Jeffrey Sachs, who directed the United Nations Millennium Project: âMobile phones and wireless internet end isolation, and will therefore prove to be the most transformative technology of economic development of our time.' But there are two very different conclusions drawn about whether this world is converging or not. Steve Jobs, as reported by his biographer Walter Isaacson, describes a moment when, in Istanbul and listening to a talk on the history of Turkey, he thought it was:

The professor explained how the coffee was made very different from anywhere else, and I realized, âSo fucking what?' Which kids even in Turkey give a

shit about Turkish coffee? All day I had looked at young people in Istanbul. They were all drinking what every other kid in the world drinks, and they were wearing clothes that look like they were bought at the Gap, and they are all using cellphones. They were like kids everywhere else. It hit me that, for young people, this whole world is the same now. When we're making products, there is no such thing as a Turkish phone, or a music player that young people in Turkey would want that's different from one young people elsewhere would want. We're just one world now.

I respectfully disagree. Turkish youth will find their own ways to use Turkish phones. The stories told in this book show how diverse mobile technologies and cultures have been. The global trade routes are extraordinary â recall the case of American phones being recycled by Pakistani wholesalers based in Kowloon, and then being purchased by Nigerian middlemen for their home marketÂ. But also recall that when the phones reached rural Nigeria they were used in ways quite distinct from the original American patterns. We may all be in constant touch but that does not mean the world is flat.