Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) (265 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) Online

Authors: OSCAR WILDE

Oscar was naturally disappointed with the criticism, but the sales encouraged him and the stir the book made and he was as determined as ever to succeed. What was to be done next?

The first round in the battle with Fate was inconclusive. Oscar Wilde had managed to get known and talked about and had kept his head above water for a couple of years while learning something about life and more about himself. On the other hand he had spent almost all his patrimony, had run into some debt besides; yet seemed as far as ever from earning a decent living. The outlook was disquieting.

Even as a young man Oscar had a very considerable understanding of life. He could not make his way as a journalist, the English did not care for his poetry; but there was still the lecture-platform. In his heart he knew that he could talk better than he wrote.

He got his brother to announce boldly in

The World

that owing to the “astonishing success of his ‘Poems’ Mr. Oscar Wilde had been invited to lecture in America.”

The invitation was imaginary; but Oscar had resolved to break into this new field; there was money in it, he felt sure.

Besides he had another string to his bow. When the first rumblings of the social storm in Russia reached England, our aristocratic republican seized occasion by the forelock and wrote a play on the Nihilist Conspiracy called

Vera

. This drama was impregnated with popular English liberal sentiment. With the interest of actuality about it

Vera

was published in September, 1880; but fell flat.

The assassination of the Tsar Alexander, however, in March, 1881; the way Oscar’s poems published in June of that year were taken up by Miss Terry and puffed in the press, induced Mrs. Bernard Beere, an actress of some merit, to accept

Vera

for the stage. It was suddenly announced that

Vera

would be put on by Mrs. Bernard Beere at The Adelphi in December, ‘81; but the author had to be content with this advertisement. December came and went and

Vera

was not staged. It seemed probable to Oscar that it might be accepted in America; at any rate, there could be no harm in trying: he sailed for New York.

It was on the cards that he might succeed in his new adventure. The taste of America in letters and art is still strongly influenced, if not formed, by English taste, and, if Oscar Wilde had been properly accredited, it is probable that his extraordinary gift of speech would have won him success in America as a lecturer.

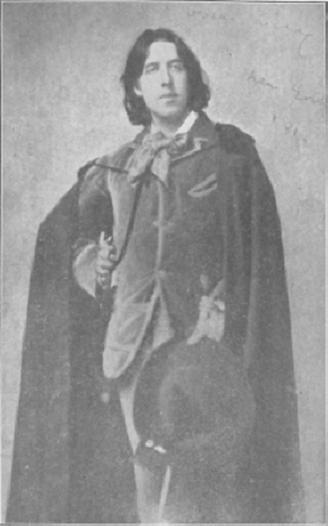

Oscar Wilde as He Appeared at Twenty-seven: on His First Visit to America

His phrase to the Revenue officers on landing: “I have nothing to declare except my genius,” turned the limelight full upon him and excited comment and discussion all over the country. But the fuglemen of his caste whose praise had brought him to the front in England were almost unrepresented in the States, and never bold enough to be partisans. Oscar faced the American Philistine public without his accustomed

claque

, and under these circumstances a half-success was evidence of considerable power. His subjects were “The English Renaissance” and “House Decoration.”

His first lecture at Chickering Hall on January 9, 1882, was so much talked about that the famous impresario, Major Pond, engaged him for a tour which, however, had to be cut short in the middle as a monetary failure.

The Nation

gave a very fair account of his first lecture: “Mr. Wilde is essentially a foreign product and can hardly succeed in this country. What he has to say is not new, and his extravagance is not extravagant enough to amuse the average American audience. His knee-breeches and long hair are good as far as they go; but Bunthorne has really spoiled the public for Wilde.”

The Nation

underrated American curiosity. Oscar lectured some ninety times from January till July, when he returned to New York. The gross receipts amounted to some £4,000: he received about £1,200, which left him with a few hundreds above his expenses. His optimism regarded this as a triumph.

One is fain to confess today that these lectures make very poor reading. There is not a new thought in them; not even a memorable expression; they are nothing but student work, the best passages in them being mere paraphrases of Pater and Arnold, though the titles were borrowed from Whistler. Dr. Ernest Bendz in his monograph on

The Influence of Pater and Matthew Arnold in the Prose-Writings of Oscar Wilde

has established this fact with curious erudition and completeness.

Still, the lecturer was a fine figure of a man: his knee-breeches and silk stockings set all the women talking, and he spoke with suave authority. Even the dullest had to admit that his elocution was excellent, and the manner of speech is keenly appreciated in America. In some of the Eastern towns, in New York especially, he had a certain success, the success of sensation and of novelty, such success as every large capital gives to the strange and eccentric.

In Boston he scored a triumph of character. Fifty or sixty Harvard students came to his lecture dressed to caricature him in “swallow tail coats, knee breeches, flowing wigs and green ties. They all wore large lilies in their buttonholes and each man carried a huge sunflower as he limped along.” That evening Oscar appeared in ordinary dress and went on with his lecture as if he had not noticed the rudeness. The chief Boston paper gave him due credit:

“Everyone who witnessed the scene on Tuesday evening must feel about it very much as we do, and those who came to scoff, if they did not exactly remain to pray, at least left the Music Hall with feelings of cordial liking, and, perhaps to their own surprise, of respect for Oscar Wilde.”

As he travelled west to Louisville and Omaha his popularity dwined and dwindled. Still he persevered and after leaving the States visited Canada, reaching Halifax in the autumn.

One incident must find a place here. On September 6 he sent £80 to Lady Wilde. I have been told that this was merely a return of money she had advanced; but there can be no doubt that Oscar, unlike his brother Willie, helped his mother again and again most generously, though Willie was always her favourite.

Oscar returned to England in April, 1883, and lectured to the Art Students at their club in Golden Square. This at once brought about a break with Whistler who accused him of plagiarism:— “Picking from our platters the plums for the puddings he peddles in the provinces.”

If one compares this lecture with Oscar’s on “The English Renaissance of Art,” delivered in New York only a year before, and with Whistler’s well-known opinions, it is impossible not to admit that the charge was justified. Such phrases as “artists are not to copy beauty but to create it ... a picture is a purely decorative thing,” proclaim their author.

The long newspaper wrangle between the two was brought to a head in 1885, when Whistler gave his famous

Ten o’clock

discourse on Art. This lecture was infinitely better than any of Oscar Wilde’s. Twenty odd years older than Wilde, Whistler was a master of all his resources: he was not only witty, but he had new views on art and original ideas. As a great artist he knew that “there never was an artistic period. There never was an Art-loving nation.” Again and again he reached pure beauty of expression. The masterly persiflage, too, filled me with admiration and I declared that the lecture ranked with the best ever heard in London with Coleridge’s on Shakespeare and Carlyle’s on Heroes. To my astonishment Oscar would not admit the superlative quality of Whistler’s talk; he thought the message paradoxical and the ridicule of the professors too bitter. “Whistler’s like a wasp,” he cried, “and carries about with him a poisoned sting.” Oscar’s kindly sweet nature revolted against the disdainful aggressiveness of Whistler’s attitude. Besides, in essence, Whistler’s lecture was an attack on the academic theory taught in the universities, and defended naturally by a young scholar like Oscar Wilde. Whistler’s view that the artist was sporadic, a happy chance, a “sport,” in fact, was a new view, and Oscar had not yet reached this level; he reviewed the master in the

Pall Mall Gazette

, a review remarkable for one of the earliest gleams of that genial humour which later became his most characteristic gift: “Whistler,” he said, “is indeed one of the very greatest masters of painting in my opinion. And I may add that in this opinion Mr. Whistler himself entirely concurs.”

Whistler retorted in

The World

and Oscar replied, but Whistler had the best of the argument.... “Oscar — the amiable, irresponsible, esurient Oscar — with no more sense of a picture than of the fit of a coat, has the courage of the opinions ... of others!”

It should be noted here that one of the bitterest of tongues could not help doing homage to Oscar Wilde’s “amiability”: Whistler even preferred to call him “amiable and irresponsible” rather than give his plagiarism a harsher attribute.

Oscar Wilde learned almost all he knew of art

and of controversy from Whistler, but he was never more than a pupil in either field; for controversy in especial he was poorly equipped: he had neither the courage, nor the contempt, nor the joy in conflict of his great exemplar.

Unperturbed by Whistler’s attacks, Oscar went on lecturing about the country on “Personal Impressions of America,” and in August crossed again to New York to see his play “Vera” produced by Marie Prescott at the Union Square Theatre. It was a complete failure, as might have been expected; the serious part of it was such as any talented young man might have written. Nevertheless I find in this play for the first time, a characteristic gleam of humour, an unexpected flirt of wing, so to speak, which, in view of the future, is full of promise. At the time it passed unappreciated.

September, 1883, saw Oscar again in England. The platform gave him better results than the theatre, but not enough for freedom or ease. It is the more to his credit that as soon as he got a couple of hundred pounds ahead, he resolved to spend it in bettering his mind.

His longing for wider culture, and perhaps in part, the example of Whistler, drove him to Paris. He put up at the little provincial Hotel Voltaire on the Quai Voltaire and quickly made acquaintance with everyone of note in the world of letters, from Victor Hugo to Paul Bourget. He admired Verlaine’s genius to the full but the grotesque physical ugliness of the man himself (Verlaine was like a masque of Socrates) and his sordid and unclean way of living prevented Oscar from really getting to know him. During this stay in Paris Oscar read enormously and his French, which had been school-boyish, became quite good. He always said that Balzac, and especially his poet, Lucien de Rubempré, had been his teachers.

While in Paris he completed his blank-verse play, “The Duchess of Padua,” and sent it to Miss Mary Anderson in America, who refused it, although she had commissioned him, he always said, to write it. It seems to me inferior even to “Vera” in interest, more academic and further from life, and when produced in New York in 1891 it was a complete frost.

In a few months Oscar Wilde had spent his money and had skimmed the cream from Paris, as he thought; accordingly he returned to London and took rooms again, this time in Charles Street, Mayfair. He had learned some rude lessons in the years since leaving Oxford, and the first and most impressive lesson was the fear of poverty. Yet his taking rooms in the fashionable part of town showed that he was more determined than ever to rise and not to sink.

It was Lady Wilde who urged him to take rooms near her; she never doubted his ultimate triumph. She knew all his poems by heart, took the strass for diamonds and welcomed the chance of introducing her brilliant son to the Irish Nationalist Members and other pinchbeck celebrities who flocked about her.

It was about this time that I first saw Lady Wilde. I was introduced to her by Willie, Oscar’s elder brother, whom I had met in Fleet Street. Willie was then a tall, well-made fellow of thirty or thereabouts with an expressive taking face, lit up with a pair of deep blue laughing eyes. He had any amount of physical vivacity, and told a good story with immense verve, without for a moment getting above the commonplace: to him the Corinthian journalism of

The Daily Telegraph

was literature. Still he had the surface good nature and good humour of healthy youth and was generally liked. He took me to his mother’s house one afternoon; but first he had a drink here and a chat there so that we did not reach the West End till after six o’clock.

The room and its occupants made an indelible grotesque impression on me. It seemed smaller than it was because overcrowded with a score of women and half a dozen men. It was very dark and there were empty tea-cups and cigarette ends everywhere. Lady Wilde sat enthroned behind the tea-table looking like a sort of female Buddha swathed in wraps — a large woman with a heavy face and prominent nose; very like Oscar indeed, with the same sallow skin which always looked dirty; her eyes too were her redeeming feature — vivacious and quick-glancing as a girl’s. She “made up” like an actress and naturally preferred shadowed gloom to sunlight. Her idealism came to show as soon as she spoke. It was a necessity of her nature to be enthusiastic; unfriendly critics said hysterical, but I should prefer to say high-falutin’ about everything she enjoyed or admired. She was at her best in misfortune; her great vanity gave her a certain proud stoicism which was admirable.