Double Victory (14 page)

Authors: Cheryl Mullenbach

The Greer family had nothing on the O'Bryant family of Augusta, Georgia. Tessie O'Bryant sent three daughters off to join the WAACs. Tessie Theresa, Ida Susie, and Essie Dell O'Bryant had decided to join the WAAC together, but when they went to sign up, Essie was sent home because she was underweight. She returned home, andâwith the help of family and friends, including the neighborhood grocerâEssie Dell gained enough weight in a month's time to join her sisters. By the time Essie Dell got to Fort Des Moines to begin her basic training, Tessie Theresa had just completed her basic training, and Ida Susie was already an auxiliary stationed at Camp Atterbury, Indiana. But it wasn't only the O'Bryant

women

who were doing their part for the warâfive male cousins were serving in the armed forces as well.

In February 1943, Marie Sublett of Springfield, Illinois, joined the WAAC. Marie said she was “rarin' to go” to the training center as soon as possible. It wasn't unusual for a new recruit to feel this way. The idea of serving in the military during wartime sounded exciting to plenty of young girls in the 1940s. But Marie wasn't a young girl. Marie held the distinction of being the first black

grandmother

WAAC!

Marie said she joined the WAAC for a number of reasons. She wanted to work as a recruiterâenlisting other black women. Marie's family and friends thought she'd be good at recruitment work. She seemed to have a knack for judging character in people. One of her favorite pastimes was “watching people.” “They fascinate me,” she said.

Marie wasn't the first person in her family to serve in the military. Her grandfather had served in the Civil War, and her

husband, Robert, had served in the First World War. Robert inspired her to join the WAAC. Marie joked, “I thought I'd serve in the second world war to catch up with my husband.”

But Marie wasn't joking when she explained, “I feel that I have served my community by raising a family, and now that a larger opportunity has presented itself to serve my country, I gladly offered my services.”

Field Assignments

The idea of women serving in the military wasn't popular with some men in 1942. There were male military leaders who thought women would be more trouble than they were worth. Some thought women could not handle the work required of military personnel. They were reluctant to allow the WAACs on their military bases. And some were especially reluctant to let

black

WAACs on their bases.

WAACs were assigned to bases around the country based on requests from the commanding officers at the installations. Some were willing to use black WAACsâbut not for the types of jobs the WAACs were trained to do. Officials said they couldn't imagine how black WAACs could be used other than in “laundries, mess units, or salvage and reclamation shops.” These were jobs that required little training or special skills, and they were considered unpleasant assignments. But it was insulting to expect WAACs who had received weeks of specialized training to take these positions just because they were black.

The reluctance of army leaders to request WAACs meant that many of the women who had completed basic training and specialist training and were in the staging centers waited for long periods of time before they were requested at field assignments. The women became very discouraged as the time went on.

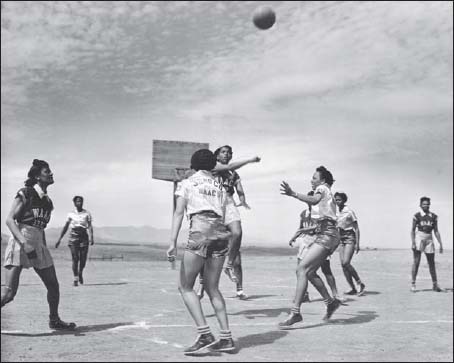

Members of the 32nd and 33rd Companies' Women's Army Auxiliary Corps basketball team take some time to relax from their duties with a game of basketball at Fort Huachuca, Arizona.

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; The New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations; United States Office of War Information Army Signal Corps

One military camp that welcomed WAACsâand specifically black WAACsâwas Fort Huachuca, Arizona. Fort Huachuca was eager to welcome black WAACs because it was a base that housed the 92nd Division of the armyâan all-black division of men. With the arrival of WAACs, the men would be available for combat duty.

Early in December 1942 two companies of WAACsâthe 32nd and 33rdâbecame the first WAAC companies assigned to an army training post. As they stepped off the train at Fort

Huachuca they were cheered by a “welcoming committee” of thousands of soldiers. They stood in perfect military salute as the national anthem played. They enjoyed a hearty lunch and then were escorted to their spacious, well-equipped barracksâcalled WAACvilleâto unpack and begin to settle into their new lives. On Saturday night a dance was held to make the WAACs feel at homeâand to give the men a chance to perform some “mad jitterbugging” before shipping out for combat assignments.

The WAACs at Fort Huachuca, two companies that consisted of close to 150 auxiliaries, were commanded by women who had graduated with the first class of officers at Fort Des Moines in August: Frances Alexander, Natalie Donaldson, Violet Askins, Irma Cayton, Vera Harrison, Mary Lewis, and Corrie Sherard.

The auxiliaries were well prepared to take over the jobs of the departing soldiers. They knew they had a tough time ahead. As Clara Monroe, Vernice Weir, Helen Amos, and Eula Daniels hoisted luggage and moved equipment around their barracks, they said they weren't concerned with nail polish or evening dresses “for the duration.” They were out to prove that women could “soldier with the best men.” They would be working as typists, stenographers, clerks, messengers, receptionists, switchboard operators, librarians, medical technicians, and photographers. Women who worked as postal clerks were lovingly known as “postal packin' mamas.”

One of the postal packin' mamas was Consuela Bland from Keokuk, Iowa. Consuela was an accomplished soprano before joining the first class of WAAC auxiliaries in August 1942. At Fort Huachuca she was receptionist and chief mail clerk. This was considered one of the most important jobs on the base because the soldiers were far from family and friends and treasured letters from home. But the soldiers showed they also appreciated

Consuela's musical talents when they gave her a standing ovation at a performance in the base chapel. Auxiliary Mercedes Welcker-Jordan, another former entertainer, had written the official WAAC song, “We're the WAACs,” and quickly settled in as a motor transport specialist. Margaret Barnes, a former javelin champ, also began her duties in the motor pool at Fort Huachuca. Myrtle Gowdy from New York City and Glennye Oliver from Chicago worked in the personnel office. Marjorie Bland (Consuela's sister), Georgia Harris, and Thelma Johnson worked in the fort's 950-bed hospital, which was staffed with all black personnel. Ernestine Hughes, a newspaper reporter before the war, wrote articles for the post newspaper, the

Apache Sentinel.

Mayvee Ashmore was a librarian at Service Club No. 1. Wilnet Grayson, a former cosmetologist from Richmond, Virginia, had completed motor transport training where she learned how to operate and maintain army vehicles including instruction in engine repair and lubrication, vehicle recovery, blackout driving, and maneuvering trucks and tanks. However, at Fort Huachuca, Wilnet served as a chauffeur for the fort's officers. She said, “I feel it is the duty of every American woman to lend her strength and talent to help win this war.”

Auxiliaries Ruth Wade and Lucille Mayo demonstrate their ability to service trucks at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, December 1942.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WWII List #145

Hulda Defreese of Hillburn, New York, was a cartographer and blueprint technician at Fort Huachuca. She had majored in fine arts at New York University and put the skills she learned there to work in the WAAC. Her duties included drawing contour maps of the mountains surrounding Fort Huachuca. The maps were important for the soldiers when they went on military maneuvers in the mountains. Anna Russell from Philadelphia was an artist at Fort Huachuca too. She designed posters, signs, and the scenery for the post's little theater. Her cartoons, which were featured in the post newspaper, provided light moments for the soldiers. Eleanor Bracey from Toledo, Ohio, was a chemist and had one of the most important jobs on the post. She worked in the water purification and sewage disposal plant. Her job was to prevent odors escaping from the plant.

WAACs trained in the handling of all types of trucks await the command to start their vehicles at the post motor pool, Fort Huachuca, Arizona, December 1942.

National Park Service; Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site; National Archives for Black Women's History/Photo by US Army Signal Corps

As the war heated up in Europe, Africa, and the Pacific, more WAACs were needed to fill the jobs on bases left by soldiers going into combat. Third Officer Frances Alexander encouraged black women to join the WAACs. She said the WAAC needed more black women who had the “country's best interest at heart.” She warned potential WAACs that “glamour girls are

out

for the duration” but women “interested in the glamour of democracy and world freedom” were welcome in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps.

WAAC Becomes WAC

On September 1, 1943, a historic event occurred that changed life for the women of the WAAC. It was on this date that the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps became the Women's Army Corps (WAC). When the WAAC had been created in 1942 it was considered a supplement to the army, but was not an official branch of the service. Because of that separation, the WAACs did not get any of the benefits that male soldiers receivedâsuch as government life insurance, veterans' medical coverage, or death benefits. If a WAAC was captured by the enemy, she had

no protection under the international agreements that covered prisoners of war. All that changed when the WAAC became the WAC. The women who were in the WAAC had a choiceâgo home or join the WAC.

Most of the black women who had joined the WAAC stayed with the newly formed WAC. And just like black men in the army, black women in the WAC were forced to live under segregated conditions. Segregation was army policy.

Although male army commanders were initially reluctant to request WACs for duty, eventually women began to populate posts around the country. Black WACs were part of those groups. Black WACs were stationed at Fort Knox, Kentucky; Fort Lewis, Washington; Fort Sheridan, Illinois; Fort Sam Houston, Texas; Fort Riley, Kansas; Fort Dix, New Jersey; and many other military posts across the United States. But as the war wore on, black WACs wanted to go overseasâto Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific, where they knew they could do more to help the war effort. They were eager to get closer to the fighting.

WACs Go Overseas

Beginning in January 1943, white WAACs were being sent overseas to highly desired assignments. But no black units were given the opportunity to go until January 1945. The first black Army Nurse Corps members had gone overseas in 1943, but they did not have full military status.

Charity Adams had been part of the first class of officers at Fort Des Moines in 1942. In 1944 she held the rank of major, and she was ordered to report to Washington, DC, late in December. Within a short time she learned that she was going overseas and would command a unit of black WACs. But she had no

idea where she was assigned, and she didn't know what her unit would be doing.