Double Victory (12 page)

Authors: Cheryl Mullenbach

IN THE MILITARY

“Will All the Colored Girls Move Over on Th is Side”

I went to the coffee shop for breakfast, but I was told I could not be served unless I desired to eat in the back of the shop. I left the place unserved because I know that I could be lynched in the U.S. uniform as well as a man in overalls.

âLouise Miller

“Will all the colored girls move over on this side.”

Everyone knew it wasn't a question. It was a command.

At the sound of those words, a small group of black women who were about to make history stepped aside as a much larger group of white women were called by name, one by one, and led off to their new living quarters.

New quarters also awaited the black women. But the living quarters that housed the black women were separate from the whites.

The women were the first to serve in a newly formed organization called the Women's Army Auxiliary Corpâthe WAAC. The womenâor “WAACs” as they were calledâwere settling into their new homes at Fort Des Moines, Iowa.

The WAAC had been established a few months earlier by the US Congress. With so many men needed to fight on the battlefields, the government decided to use women to help in noncombat jobs. A bill was introduced by Rep. Edith Nourse Rogers, and on May 15, 1942, the WAAC was created.

Women's Auxiliary Army Corps Is Formed

The women who arrived in Fort Des Moines in July 1942 were members of the first WAAC officer candidate class. As officers, these women would train and lead the enlisted WAACs, called the auxiliaries. Most of the officer candidates were women who had attended college; many were college graduates and had been working as teachers, secretaries, or social workers in civilian life.

The plan called for a total of 440 women to make up the first group of officer candidates. Forty were to be black women. In 1942, an estimated 10 percent of the population in the United States was black, so Congress decided to limit the percentage of blacks in the WAAC to 10 percent as well. The group of black candidates became known as the Ten Percenters.

When the idea of forming the WAAC was brought up, owners of black newspapers and leaders in black communities wrote letters asking the president and Congress to include black women in the corps. Mary McLeod Bethune was working in the War Department in Washington, DC, when discussions began about forming the WAAC. Mary did all she could to make sure black women were given a chance to train as officer candidates.

When the decision was made to allow black women to serve in the WAAC, many black people across the country were pleased. But when it became known that the WAAC would “follow the policies of the regular Army,” which included segregating the races, they were very disappointed. Military officials explained that the policy of separating black and white soldiers had been in place for a long time and that they believed the practice worked well for “everyone.” They ignored the fact that it

didn't

work well for black soldiers who were restricted to certain jobs within the military and denied basic civil rights.

When a woman from a southern state was appointed director of the WAAC, many black women were disheartened and skeptical of her capacity to be fair when racial issues arose. The director, Oveta Culp Hobby, promised that there would be no “deliberate displays of discrimination,” but she said the separation of the races would be necessary. She explained, “The Women's Army Auxiliary Corps will follow in general the policies of the regular army of the United States. These policies have been long-formulated and have been found to be workable and time-tested.” The army refused to admit that racial segregation was discrimination.

Organizations that had been fighting for equality for black women in the WAAC said they would continue the fight. A spokesperson from the National Council of Negro Women said, “Now is the time to change the âpresent procedure' of the army. If we can't have democracy now, when in heaven's name are we going to have it?”

Recruitment

“This is a woman's war as well as a man's war. Every woman must do her part. One way to do your part is to join the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps.” These words appeared on the back cover of a government brochure that outlined the requirements for the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1942.

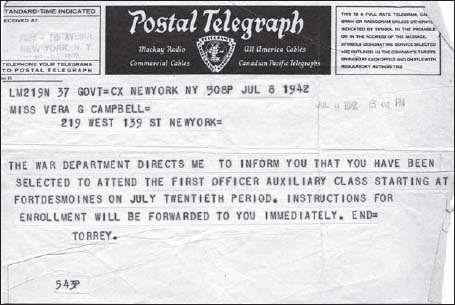

Telegram sent to Vera Campbell, a black podiatrist from New York, announcing her acceptance in the first class of officers in the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps, 1942.

Fort Des Moines Museum and Education Center; Vera Campbell Collection

Across the country, posters, brochures, and newspaper ads encouraged women to support the war effort by joining the WAAC. The hope was that women would take the words seriously and apply for the WAAC officer positions or the lower-ranking auxiliary openings.

By May 27, army recruiting stations around the country had been supplied with 90,000 application forms. The response was astonishing. WAAC headquarters in Washington, DC, was swamped with women eager to join. Local recruiting stations were flooded with applicants.

The requirements were straightforward. Candidates had to be between the ages of 21 and 45, stand at least five feet tall, and weigh 100 pounds or more. Single and married woman could apply. If mothers could prove that their children would be cared for during their absence, they could join. Black women were encouraged by leaders in the black communities to apply, but some reported that officials at recruiting stations refused to give them application forms.

All across the country black women responded to the call for women to “do their part.” In Chicago two friends, Violet Ward Askins and Mildred Osby, applied together. Charity Adams had just completed her fourth year as a math teacher in Columbia, South Carolina, when she received a written invitation and application form from the WAAC asking her to apply to the first officer training. She had been recommended by the dean of her college. Mildred Carter, a graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music, had danced in Broadway productions and was the first black woman to perform with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. She was operating her dance studioâthe Silver Box Studiosâin Boston, where she taught ballet, tap, and interpretative dance, when she left to enter the first class of WAAC officers. Vera Campbell, a podiatrist from New York, and Cleopatra Daniels, a school superintendent from Alabama, also volunteered.

Dovey Johnson's grandmother was a personal friend of Mary McLeod Bethune, so when Mary encouraged Dovey to apply to the first WAAC officer class, she entered the recruiting station in Charlotte, North Carolina, with a sense of confidence and asked for an application form. But the white army recruiter tried to squash Dovey's enthusiasm by shouting at herâand ordering her out of the building. He threatened to have her arrested. So Dovey traveled to a city north of Charlotte where

she hoped to escape Jim Crow practices. In Richmond, Virginia, Dovey finally was able to complete an applicationâresulting in her acceptance into the first class of officer candidates.

By June 4âthe deadline for submitting completed application formsâover 30,000 women had gotten forms and returned them to local recruiting stations across the country. Four hundred and forty would be chosen to attend officer candidate training. The others would be auxiliaries.

The black women who applied to officer candidate school gave many reasons for their interest in the WAAC. “At this time of history when the entire world is at war, it is the duty of every citizen, regardless of race or creed, to do his share to bring back peace and security to our country,” explained Mary Frances Kearney of Bridgeport, Connecticut. “If we are to win the war, it must be won with the help and cooperation of all of us,” said Cleopatra Daniels.

Some of the candidates said they were looking for an adventure. Some were bored with their civilian jobs. Some of the black women believed Oveta Culp Hobby when she said that the WAAC would offer “equal opportunity for all.”

And Director Hobby reminded everyone that “American women have not failed to realize that they owe a debt to democracy. A debt in return for all the privileges which they have enjoyed as free citizens of a free nation.”

With many women applying for the officer candidate slots, the government came up with a way to choose the best candidates. The applicants had to write an essay titled “Why I Desire Service.” They were also given an aptitude test. This helped officials learn about the different skills each woman had. Those who passed the aptitude test were interviewed. The next step was a physical exam. Those who passed the physical exam were given another interview. During the second interview many personal

questions were asked about the women's school records, families, and hobbies.

Basic Training

Throughout the day and night of July 20, young womenâblack and whiteâarrived at Fort Des Moines. They had traveled to Iowa on buses or trains from across the United States. They were met at the station and transported to the fort in army trucks fitted with long wooden benches. The WAAC candidates endured a bumpy ride as the trucks lumbered through the city streets.

As the WAACs passed through the gates of Fort Des Moines they entered a world of neat, red brick buildings and carefully trimmed lawns. The fort had been created as a cavalry post where soldiers who rode horses into battle were trained. Over the years thousands of male soldiersâboth black and whiteâhad been trained there. In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, black officers were trained at Fort Des Moines. Now another chapter in American history would begin at the fort. The first black women to enter the WAAC would spend the next few weeks making history there.

Before the WAACs arrived at the fort the old horse stables had been converted into buildings for their use. The street where the barracks stood became known as Stable Row. Some women claimed they could still smell horses in their living quarters!

The very first candidate to arrive at the fort was a black officer candidate named Bessie Mae Jarrett. Just a month before, she had graduated with honors from Prairie View State College in Texas. Soon after her arrival, more candidates began to come from across the country. These new arrivals were white. Several days passed before more black candidates arrived to join Bessie, who was living alone in her segregated barrack.

The black WAACs settled into Building 54, where each woman was assigned a cot and two lockersâa tall green one for uniforms and a smaller one for underclothes, gloves, and equipment. The bathrooms were in the basement.

At the mess hall the black WAACs were again confronted with the ugliness of segregation. A sign had been placed over a table in one area of the room. The sign had the word “Colored” written on it. The black women sat down and ate their meal. But the next day they had a plan. They marched into the mess hall and sat at the table marked “Colored” as they had the day before. Instead of getting into the line to get their food, the black women turned their plates over and refused to eat. The next day when they entered the mess hall the sign had been removed. But a card had been placed on the table. “For C” was printed on the card. Once again the black women turned their plates over and refused to eat. Within a week all the signs had been removed.