Double Victory (26 page)

Authors: Cheryl Mullenbach

Chairwoman of the Hollywood Victory Committee's Negro Division Hattie McDaniel (center) takes time off from rehearsals to lead a caravan of entertainers and USO hostesses for a performance and dance for soldiers stationed at Minter Field in Southern California.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WW II List #216

In April 1942 some Hollywood stars formed the Hollywood Victory Committee. Members of the committee pledged to provide support for the war through appearances at bond rallies and through performances at military training camps and hospitals. Big-name stars joined the groupâClark Gable, Bette Davis, Carole Lombard, Dale Evans. Some entertainers volunteered their timeâothers were paid. But the Hollywood Victory Committee segregated the black entertainers in the organization.

A black actress named Hattie McDaniel was selected to head up the “Negro talent” for the black Hollywood Victory Committee. Hattie encouraged other black entertainers to join the committee, and together they coordinated the work of black performers who did their part for the war effort through radio broadcasts and live appearances. Hattie not only organized, she also performed at camps at least once a week. Hattie's work helped contribute hundreds of thousands of dollars to the war bond drives, and her personal appearances helped boost the morale of thousands of American servicemen and -women.

But Hattie's contributions to the war effort meant nothing to a group of homeowners who lived near her in a Los Angeles neighborhood. They didn't see Hattie as a person who had worked to help America win the war; they saw a black woman living in a white neighborhood. And that was not acceptable to them.

A Maid, but Not a Servant

Black Americans who wanted to work in Hollywood in the 1940s had few choices when it came to movie roles. Black actors seldom appeared in movies. And when they did, men were cast as buffoons and women as maids. On the occasions when black actors and actresses were portrayed in roles outside the

stereotypes, Hollywood sent special versions of the films to movie theaters in the southern statesâversions with the scenes racist white moviegoers would deem “offending” cut out. When it wasn't possible to cut scenes, the movie producers assured the southern theater managers that black theaters and white theaters would get the movies at the same time so white moviegoers wouldn't have to worry about black moviegoers trying to see the movie in the white theaters.

Hattie McDaniel was a talented actress, singer, songwriter, and comedian and could have performed well in many different roles. But she ended up as a maid more times than not. Hattie looked at it this way: “It's better to get $7,000 a week for playing a servant than $7 a week for being one.”

While Hollywood was only interested in seeing Hattie as a maid, black soldiers appreciated her rousing song and dance performances. They forgotâjust for a whileâthat they were soldiers about to ship out when they heard her comedy routines. Hattie took her job as the head of the black Hollywood Victory Committee very seriously.

In April 1942, Hattie wowed newly arrived soldiers at an army camp near San Bernardino, California, with her singing and dancing. The soldiers brought down the house with applause and crowded around her begging for autographs so they could prove to their families back home that they'd seen the famous star. In June Hattie coordinated a star-studded show for soldiers at Camp Hahn in San Bernardino County in California. In July Hattie organized an event in Hollywood for servicemen on leave. It included a parade and bowling party. Hattie and the other stars she had lined up bowled along with the soldiers. At the end of the day, the soldiers enjoyed Hattie's hilarious comedy act. In August 1942, Hattie organized a caravan of stars to the southwestern mountains where the soldiers

of the segregated black 10th Cavalry Unit of the US army were training. By October Hattie was on the road to Indiana, where the US Treasury Department had asked her to drum up interest in the “Interracial War Bond Rally.” She had special leave from the Hollywood studio where she was in the midst of filming a movie. In April 1943, Hattie organized a group of black entertainers for an event at Camp Young near Indio, California. The 85-mile-per-hour winds from a desert dust storm didn't stop the singers and dancers from entertaining the 25,000 soldiers who had come to see them. After the stage performance the stars headed to the hospital to visit with the patients. In June 1943, Hattie performed at an event to launch a campaign to raise $175,000 in war bonds to buy a bomber.

Hattie McDaniel was admired for the work she did with the Hollywood Victory Committee, and she was respected by many Americans for being the first black actor to win an Oscar. Some people criticized her because she accepted movie roles in which she played a stereotypeâa black “mammy” with a kerchief on her head in

Gone with the Wind.

It gave the impression that Hattie McDaniel was a meek, submissive type. But in 1945, Hattie did something that made everyone look at her with renewed respect.

Sometimes when Hattie and the Hollywood Victory Committee were planning their events they met at Hattie's house in an area of Los Angeles known as the Sugar Hill neighborhood. A number of black stars and businesspeople had purchased homes there after they had made it in Hollywood.

In the 1940s some cities or neighborhoods had racially restrictive covenants, which were contracts that prohibited the purchase, lease, or even occupation of property by specific groups of peopleâoften black people. It meant that black people were frequently denied housing based on the color of their skin. And at that time it was legal.

A typical covenant read like this: “No person or persons of African or Negro blood, lineage, or extraction shall be permitted to occupy a portion of said property.”

After Hattie paid for her house and moved in, a group of white residents in the neighborhood filed a legal complaint against the black homeowners. The complaint said the original owners of the homes did not have the right to sell to blacks. Therefore, Hattie and the other black homeowners were living in their Sugar Hill houses illegally and had to leave. If they refused, they would be evicted!

Hattie and some of her black neighbors decided to fight back. They found an attorney who agreed to take their case. In December 1945 the case was heard in a Los Angeles courtroom. Judge Thurmond Clarke presided. For two hours the judge listened to the opposing lawyers. Spectators in the courtroom noticed a portrait of Abraham Lincolnâthe president who had freed the slavesâbehind Judge Clarke. “I hope that judge has eyes in the back of his head,” one black man commented.

The next morning the judge had reached his decision: “It is time that members of the Negro race are accorded, without reservations or evasions, the full rights guaranteed them under the 14th Amendment to the federal Constitution. Judges have been avoiding the real issue too long.” And with that, Judge Clarke threw the case out of court!

Hattie McDaniel had played the part of an obedient servant in movies because Hollywood wouldn't let her show her true strengths as a singer and performer. When she was confronted with an unjust law in the real world, Hattie showed that she had plenty of strength. She refused to play the part of an obedient servant. She had gone above and beyond to serve her country in its time of need, and she refused to let a few of her neighbors force her out of her home.

“Whatever I can contribute I am only too anxious to. When I look around me and see how the men and women of Hollywood all are joined in magnificent support of the war effort, I realize how completely this is a struggle which demands the most of all of us,” Hattie explained.

Lena Quits

Lena Horne was one of the rare black performers who had starred in Hollywood moviesânot with speaking parts, but as a singer. That made it easier to cut her scenes from the movies when they played in the South. Still, Lena was gaining acclaim as a performerâfrom white as well as black audiences. Her tour of the South was part of a USO tour arranged by the Hollywood Victory Committee.

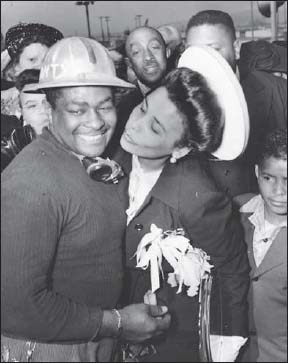

Lena Horne kisses Montrose Carrol, a worker at the Kaiser Company Shipyard in Richmond, California, May 1943.

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; The New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations; US Office of War Information, E. F. Joseph, Photographer

One night in 1944 when she was scheduled to perform, Lena peeked out at the audience from backstage. She saw only white soldiers. Lena had performed many times at military camps, and she was used to seeing white soldiers in the front seats of the auditoriums while the black soldiers sat in the back or in a balcony. That was typical, and it always made Lena angry. But she wanted to perform for the soldiers, and she knew that the military was segregated so there wasn't much she could do about it. But on this occasion Lena didn't see

any

black soldiers in the auditorium. When she asked where the black soldiers were, she was told that she would be performing for them the next morningâin their mess hall. It meant Lena and her band would have to stay overnightâsomething she hadn't planned. But she agreed so that the black soldiers at the camp could see her perform.

The next morning Lena arrived at the black mess hall. This time when she looked out at the audience she saw more white men in the front rows. The black soldiers were in the back.

“Now who the hell are

they

?” Lena asked.

“They're the German prisoners of war,” someone explained.

Lena was furious. She stepped down from the stage, moved to where the black soldiers sat, turned her back on the German prisoners, and sang a few songs to the black soldiers. But she wasn't able to complete the performance because she was so upset about the disrespect shown the black soldiers.

Lena Horne quit her USO tours after the incident. She didn't quit performing for the soldiers, however. She continued to visit bases all over the country throughout the war. But she paid her own wayâso she could show the black soldiers the respect they deserved.

Morale Builders

Lena Horne's tour to the South in 1944 had been sponsored by the USO. The organization had begun to play a major role in providing entertainment for the troops in October 1941. The USO tours were called camp shows. These live shows toured the United States military training camps, and eventually shows went overseas. Actors, musicians, singers, dancers, and comedians were eager to show their patriotism by performing.

The camp shows were segregatedâwhite entertainers in white shows for white soldiers, black entertainers in black shows for black soldiers. By 1942 black camp show units were touring military camps across the country. Many black womenâsingers, dancers, musicians, actresses, and comediansâperformed, and they were a hit. Each show comprised a variety of acts combined under one title.

Swing Is the Thing, Harlem on Parade, Sunset Orchestra Revue, Swingin

'

On Down, Sepia Swing Revue,

and

Rhythm and the Blues

featured unknown performers and big-name stars. The Three Cabin Girls, Caterina Jarboro, the Three Spencer Sisters, Julie Gardner, Rosetta Williams, Gwen Tynes, the Smith Sisters, Sandra Lee, Rosalie Young, Laura Pierre, and Martha Please were black entertainers who worked for the “Negro talent” division of the camp shows.

Ella Fitzgerald sang in a camp show at Fort Jay, New York, in early 1942. She sang some of her favoritesâ“You Showed Me the Way,” “Good Night My Love” and “I'm the Lonesomest Gal in Townâfor the servicemen. Blues singer Bette St. Clair and tap dancer Evelyn Keyes traveled with the

Sepia Swing Revue

in 1942. The camp show

Keep Shufflin'

traveled throughout the Midwest in 1943 and starred the Three Shades of Rhythm, a “girl group” from California. Late in 1943, soldiers about to ship

out were entertained by Una Mae Carlisle and Ann Cornell at Camp Shanks, near New York City. Camp Shanks, nicknamed Last Stop, USA, by the soldiers, was a camp used exclusively for deployment of troops overseas. Una sang two songs she had writtenâ“Walkin' by the River” and “I See a Million People.” Ann sang “You'll Come Back.”

In April 1943 the

Afro American

newspaper reported that the USO had 266 entertainers in 45 units in overseas shows, but not one black entertainer was among them. But by fall 1943 the first black camp shows had begun to perform in a series of shows known as the Foxhole Circuit.

The first overseas show starring black entertainers performed for British and American servicemen in Cuba, the Bahamas, Haiti, Jamaica, the Virgin Islands, Antigua, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and British and Dutch Guiana. Comedian Willie Bryant acted as the master of ceremonies, introducing acts that included blues singer Betty Logan and Julie Gardner, an accordionist and singer.

While playing one of their first stops on the tour, the entertainers received a call from a supply ship stocked with a crew eager to see a live performance at sea. The entertainers were bundled onto a plane and within a few hours they were aboard a troop ship with all its identification marks carefully covered. They went aboard, put on their show, and flew back to the base. None of the performers ever knew where they had been, but they all knew how much the sailors appreciated their efforts. While they were aboard the ship, they said they were treated like royalty. Julie Gardner had performed her rendition of “Pistol Packin' Mamma.” Betty Logan, known as the Brown Bombshell, sang the new hit “Chicken Ain't Nothin' But a Bird.”