Drama (31 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

“Well, I have something for you,” he said.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Mary Yeager.”

W

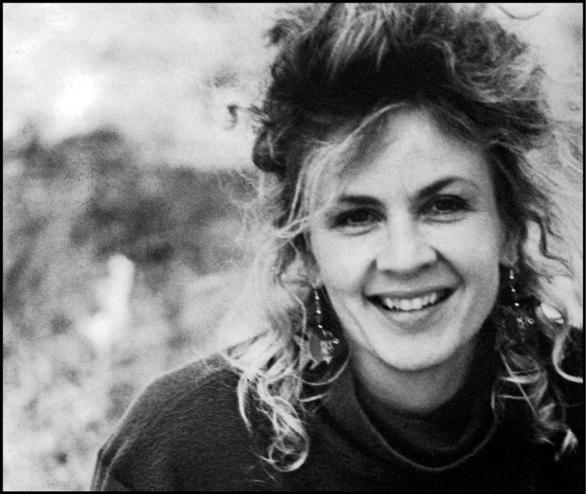

alter proceeded to tell me all about a friend he’d made since arriving in town. It was a story that grew more intriguing with every sentence. Mary Yeager was a professor of economic history at UCLA. Considering the tweedy mustiness of academia, she was a stunning anomaly—blond, blue-eyed, and attractive, with a passing resemblance to the young Julie Christie. She had grown up a farm girl on the plains of northern Montana, but from childhood she had methodically plotted an escape from her preordained life as a farmer’s wife. Her planned escape route was an East Coast college. Her farmer father had only allowed her to apply to two schools, refusing to pay for more than two application fees. She’d selected Smith and Middlebury. Sadly, she was turned down by both. After receiving her rejection letters, she wept for two days. Then she wrote a letter to the admissions officers at Middlebury and told them she was coming anyway. Taken aback by her fierce tenacity, they agreed to make room for her after all.

The following September, as if grabbing the last stagecoach out of town, Mary Yeager left Montana behind her. She spent four grueling years at Middlebury, struggling to fill the holes in her small-town Montana public school education. After Middlebury, she earned a Ph.D. in history at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Then she won an appointment as the first-ever female tenure-track history professor at Brown. Finally she had ended up on the faculty of UCLA, two years before my supper with Walter Teller at El Coyote. By now she was thirty-five years old, just like me. She had married young, but, like me, her marriage had ended three years before. Walter had been going with a longtime girlfriend during the entire time he had known Mary, but as he recounted her story it was clear that he adored her. And something told him that she and I were exactly right for each other.

Walter fixed us up. With lawyerly craft, he hatched a benign two-faced plot. He told Mary that we would swing by on a Saturday and take her out to lunch. Telling me nothing of the plan, he proposed that he and I play tennis that same morning on a public court near her home. That Saturday, after two sweltering hours of tennis, he blithely suggested to me that we drop by Mary Yeager’s apartment and see if she wanted to join us for a bite to eat. I liked the idea. As we pulled up to her Santa Monica address, I noted that her apartment was in a building situated at the corner of Montana Avenue and Harvard Street. Montana and Harvard? The coincidence sent a tiny shiver of destiny right through me. Walter rang the doorbell and Mary opened the door, betraying not a trace of impatience at the fact that we had arrived an hour later than he had told her to expect us.

She was even prettier than Walter had described. Decked out for an elegant Santa Monica lunch date, she wore beige pants, strappy sandals, and a white cotton sweater dotted with little embroidered flowers. I, on the other hand, sported mismatched tennis gear that featured dirty gray sneakers, navy socks, and an old red polo shirt soaked with sweat. Flushed with athletic exertion, my face matched the color of my shirt. My dripping hair stuck out porcupine-style. I was a clueless embarrassment to chivalrous manhood. When Walter introduced me to Mary, I cheerily greeted her and wetly shook her hand, without the slightest notion that there was anything wrong with this picture.

Mary knew next to nothing about my world. Her closest brush with show business was at the age of eleven when her father erected the first drive-in movie theater in the state of Montana, in a wheat field outside the town of Brady. When Walter had mentioned me to Mary, she had never heard of me. I was the first actor she had ever met. I later learned that Walter had hyped me to her as “the best theater actor in New York.” This had led her to picture me as a handsome matinee idol, someone along the lines of the dark, dashing Kevin Kline (a stab in my envious heart!). So for her, my appearance on the doorstep that day was a deeply underwhelming disappointment. Her mistaken first impression of me was twofold: I was Australian, and I was gay.

Fortunately, she was too polite to slam the door in our faces. Off we went for a notably

in

elegant nosh at the long-gone Westside Delicatessen on San Vicente Boulevard. The three of us had a fantastic time. We laughed ourselves breathless for ninety minutes. When Walter and I dropped Mary off afterwards, I kissed her cheek at the curb in front of her home. We arranged to get together the next day to see a Sunday-afternoon showing of the film

Norma Rae

. We spent that entire Sunday talking and laughing on her living room couch. We never got to

Norma Rae

. I went to UCLA on Monday morning and watched her give the first lecture of her survey course on American Economic History. From her lips I heard the name “Joseph Schumpeter” for the first time. Who would have dreamed that the name “Joseph Schumpeter” could ever sound so sexy?

By Tuesday, Mary had left for an academic conference in Washington, D.C. She was gone for three days. The days were punctuated by a dozen phone calls between us. She returned just in time to go with me to a weekend barbecue for the cast of

The Oldest Living Graduate

. It was her introduction into the exotic backstage world of show business. She hobnobbed at poolside with leathery Harry Dean Stanton and callow Timothy Hutton. She chatted with Henry Fonda, the first screen legend she’d ever met in the flesh. After the barbecue, a manic Cloris Leachman insisted on giving us a Cook’s tour of her vast home, perched atop Coldwater Canyon. More bemused than starstruck, Mary navigated the events of that afternoon like a research scholar stumbling onto a captivating new field of study.

The following week, my flying visit to Los Angeles came to an end. I had spent every possible hour with Mary. I left for Dallas to perform

The Oldest Living Graduate

on television. By that time, the die was cast. Walter had been right. Mary and I were made for each other. We’ve been together ever since. It was the best deal Walter Teller ever struck.

God probably never intended for actors and professors to marry. When an actor weds a professor, they are both asking for trouble. By nature, a professor’s life is orderly and predictable. Years in advance, she knows what courses she’ll teach, what conferences she’ll attend, and what faculty committees she will serve on. She carefully doles out months and years of time to conduct research and write books. If she is to amass a substantial body of work and build a distinguished academic career, nothing must distract her from her clearly defined scholarly mission.

By comparison, an actor’s life is scatterbrained chaos. He never knows where his next job is coming from, or when. A stray phone call from his agent can send him to another continent for a three-month gig on three days’ notice. With every new offer, his career is totally rejiggered. Given a choice between jobs, he can bore the bark off a tree with his agonizing equivocations. Worse still, months can go by with no jobs at all. When this happens, an actor’s gloom and self-doubt can make him an insufferable conjugal partner. But the opposite can also apply: a professor with a book deadline or a pending promotional review is no walk in the park, either. The twin disciplines of academia and show business require two completely different emotional skill sets and temperaments. On the face of it, a marriage between an actor and a professor can never work.

Ours does. It has for thirty years. Who knows why? Perhaps our differences have somehow bound us together. Mary is earthbound and practical, I am airheaded and artistic. She is restless and mercurial, I’m phlegmatic and plodding. She is pessimistic and contrary, I’m optimistic and accommodating. She is fearless and combative, I’m fretful and politic. She is openhearted and generous, I’m self-absorbed and tightfisted. She shuns the spotlight, I am drawn to it like a heliotropic flower. Shakespeare is Greek to her, economics is Greek to me. Spectator sports? She is frostily indifferent, I am rabidly passionate. And yet from the first day we met, we have never bored each other for a second. For both of us there is no one else in the world whose company we would prefer. She has brought a tough-mindedness and reassuring order to my life, and I have brought a measure of disruptive fun and happy disorder to hers. By now, it is impossible for either of us to imagine life without the other.

After my lunch with Mary at the Westside Deli, the next four years passed with lightning speed. They were jam-packed with momentous changes for both of us. For a while we played a transcontinental tug-’o-war, struggling to choose between my life in New York and hers in Los Angeles. Mary took a sabbatical from UCLA to test the waters in Manhattan. She weighed job offers on the East Coast. We snooped around for a bigger Upper West Side apartment. One day my agent called. He’d made an appointment for me to read for a film based on John Irving’s bestselling novel

The World According to Garp

. At my audition, I read for the role of the transsexual Roberta Muldoon. Director George Roy Hill cast me as Roberta and I shot the film in and around New York. Halfway through the shoot, Mary was granted tenure at UCLA. This news abruptly ended our geographical tug-’o-war. She won. I was heading west. But before leaving town, Mary and I got married at City Hall, with nine-year-old Ian as my best man. Arriving in Los Angeles, I joined Mary in the apartment at the corner of Montana and Harvard. Ian became a frequent visitor. Mary gave birth to our daughter, Phoebe. Soon after,

Garp

was released. The next year, our son Nathan came along. We bought a house, minutes from UCLA (where we have lived ever since). Rick Nicita was my agent again and Walter Teller was now my attorney. Awards began to pile up for my performance as Roberta Muldoon. When I won the New York Film Critics’ Award, my old friend David Ansen gleefully called me with the news. Hollywood embraced me with open arms. After

Garp

, I played a back-to-back string of wildly different roles in major Hollywood films:

Twilight Zone

,

Footloose

,

Terms of Endearment

, and

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banza

i. Celebrity struck like an avalanche. I escorted Mary to the Academy Awards for two successive Oscar nominations. We barely knew what hit us. Our lives had been hurled into a completely new level of reality. If we hadn’t had each other we might not have survived our dizzying flight into the ozone. But we did. We had each other. And we’ve had each other ever since.

A cautionary tale? Indeed. But it is a cautionary tale with a difference. This cautionary tale has a happy ending, right out of O. Henry. It is an ending shot through with one blazing, life-affirming irony:

None of these things would have ever happened if I hadn’t made the biggest mistake of my career.

Let us examine for a moment what my wife’s professorial colleagues might call “a counterfactual.” I choose

Betrayal

and I celebrate a gratifying success on Broadway. But look what I miss out on? I never meet Mary Yeager. I completely forgo my life with her. Phoebe and Nathan are never born. A thousand happy events in our lives never take place—birthday parties, school plays, graduation ceremonies, camping trips, foreign countries, Christmas mornings, Halloween nights, swimming lessons, bicycle lessons, weddings, baby steps, pets. My professional life is impacted as well. I never achieve that unique dual citizenship as a Broadway and Hollywood actor that has been my calling card ever since. Everything of substance that has defined the second half of my life simply never happens. Such an alternate universe is completely inconceivable to me. Each of these things I hold near and dear. They will live in me forever, long after everyone else has lost all memory of a hit Broadway play in 1979.

And what is the moral of this story? It is a truth at the heart of my whole life:

Acting is pretty great. But it isn’t everything.

Y

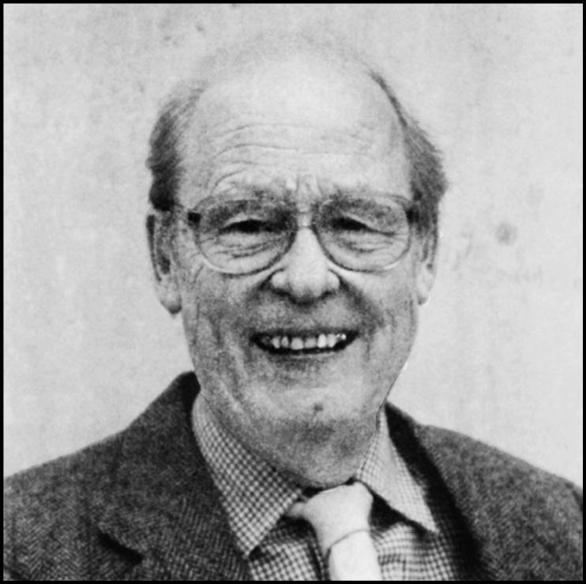

ears after my father died, my thoughts continued to dwell on memories of him. The most vivid of those memories was that evening in 2002 when I first read him a bedtime story. As I relived that evening again and again, an idea gradually began to form in my mind. On that long-ago night, my mother, my father, and I made our deepest connection with each other. But that’s not all that happened. By chance, I also stumbled across a nugget of pure gold. The nugget was called “Uncle Fred Flits By.” That Wodehouse short story was a work of comedy genius, a fine-tuned machine for manufacturing riotous laughter. Best of all, it was a story that almost no one west of the Atlantic Ocean had ever heard of. I began to imagine a theatrical performance consisting of nothing more than “Uncle Fred Flits By” enacted by a single actor on an empty stage. It would be a kind of storytelling magic act. With nothing more than the actor’s sleight of hand, four settings, ten characters, and a parrot would all come to life in front of an audience. I would be the actor. And the story, for all its loopy hilarity, would be suffused with my own poignant history with it.

With no clear notion of what I would do next, I began to commit the story to memory. I printed it out on twenty sheets of paper. Each morning and evening I would take the family dog on long, leisurely walks, carrying the pages and running my lines. Passersby would see me staring into space, working my features spasmodically, and muttering to myself. They steered clear of me without a word. I assigned myself a single paragraph for each dog walk and wouldn’t return home until it was safely stowed in my brain. After a month, the dog was exhausted, but I could recite the entire story to myself from beginning to end.

I enlisted the help of Jack O’Brien, a good friend and a splendid stage director, to help me spin “Uncle Fred” into a piece of theater. Jack was uncannily suited to the task. He and I shared a distinct strand of theatrical DNA. As a young man, he had worked with several alumni of my father’s old Ohio Shakespeare festivals, so he felt an ineffable connection to my father’s legacy. Together we approached André Bishop, artistic director of New York’s Lincoln Center Theater Company. We asked him for a rehearsal room to try the piece out. André readily obliged. The three of us assembled a group of twenty friends and well-wishers. They arrived in the subterranean Ballet Room of the Vivian Beaumont Theater on a late morning in January 2008. They had no idea what I was up to.

I spent five minutes telling the little crowd my brief history with “Uncle Fred Flits By.” I told them about my father, my mother, and my siblings. I told them about

Tellers of Tales

. I had brought along our old copy of the book, and I showed it to them. I told them about the Amherst condo and the night I read to my parents. Then, with no set other than a table and chair and with no prop other than the old book, I sat down and began to read the story out loud to them. After a few paragraphs, I looked up, took off my glasses, placed the open book on the little table, and proceeded to perform the rest of the story by heart.

The little performance was a revelation. Our friends loved it. They thought the story was hilarious. They experienced the same sense of discovery that I had felt six years before when I had read it to my folks. But most of all they were captivated by my five minutes of introductory storytelling. They wanted to hear much more of it. After they disbanded, Jack, André, and I discussed how to expand the piece into a longer evening, something more suitable to a ticket-buying crowd. Judging from the response of our little audience, stories of my own family were clearly going to be my richest source materials.

At the end of our conversation, André took a cheery leap of faith. He invited me to perform the show for several weeks that very spring, on dark nights at the little Mitzi Newhouse Theater. Jack signed on to help me mount it. Within a month I had added enough new material to forge a ninety-minute solo show. In April and May I performed it on Sundays and Mondays, fourteen times in all. It was warmly received in the press. With so few performances in such a small theater, tickets were impossible to come by. It was the biggest little hit in town. I called it

Stories by Heart

.

For the next couple of years, the show continued to evolve. I toured it to cities all over the country. I appeared in theaters, opera houses, and concert halls, in front of audiences large and small.

Galveston. Lexington. Scottsdale. Reno. I even performed it at London’s National Theatre. In every city, old friends from every chapter of my life showed up and reconnected with me. Most stirringly, I presented the show at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, at the Great Lakes Theatre Festival in Cleveland, at Harvard’s Loeb Drama Center, and at the Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, just north of Stockbridge. On those nights, ghosts hovered over the crowd and smiled warmly at me from the wings. Wherever I went, I secretly invoked the spirit of my father. I imagined him watching every performance. I picked out his booming laugh in the audience. I heard his voice in my speech and felt his movements in my limbs. I especially loved paying tribute to him from the stage and bringing him back to life, both for friends who had loved him and for people who had never heard of him. I wish he could have seen it. I think he would have liked it.

O

ld age is a hardship for a man of the theater. Live long enough and you outlast all the people who remember the events that shaped your life. In 2002, toward the end of my month in Amherst, I was chatting idly with my father in the condo living room. As I recall, my mother was busying herself in the kitchen nearby. In a few days I would leave the two of them and return to Los Angeles. Anticipating my departure, all of us were feeling a little morose. For some reason, my father and I took up the subject of theater critics. I had recently suffered through the critical failure of a big Broadway musical in which I’d played the leading role. The

New York Times

notice had been hard on the show and dismissive of me. The review had tormented my father. It was only the latest of many moments when my bad press had driven him crazy. As he had often done before, he’d even written an unsent letter of vehement protest to the

Times

reviewer. In our conversation, the two of us were trying to figure out why he took these things so hard.

“Why does it bug you so much, Dad?” I asked. “I’ve had lots of good reviews in my time and lots of bad ones. Pans really don’t bother me that much anymore. I think they upset you more than they upset me.”

“I don’t know,” he answered, perplexed. “I guess I must have some vicarious investment in what you do. I experience it all through you. After all, I didn’t have a career of great achievement . . .”

“Whoa!” I shouted. “Dad! Stop right there! You take that back! I’m not going to let you get away with that! You’ve had a

magnificent

career! Look what you created. Look how many lives you changed. You gave so many people their first jobs. You inspired them. You introduced thousands of people to theater. To Shakespeare! Strangers come up and tell me that all the time. You’re my hero. I would never have done any of this if it weren’t for you. I owe you everything. And I’m one of hundreds.

Thousands!

I’m not going to let you

say

that!”

Dad blinked and wrinkled his brow as I worked myself into a righteous passion. I ended my diatribe. After a moment’s silence, he turned toward the kitchen and called out in a tremulous voice: “Did you hear that, Sarah?”

It was deeply important for him to hear my rant, for me to deliver it, and for my mother to overhear the exchange and bear witness. It was one last gift the three of us were able to give each other. For me, it was a reaffirmation of the love and respect I felt for my father. For my mother it was a validation of her long life of unstinting support for him. And for him it was one last round of applause, one last rave review, one last ovation. Nine years later, at the beginning of 2011, I completed this book. I have come to see it as their story as much as mine. If you have reached this sentence, you yourself have finally finished it. This particular drama has come to an end. It is time for me to take a bow, wave to the crowd, and leave the stage.