Drama (28 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

But in this bright picture there were dark shades. For one thing, my parents had entered a period of impermanence and anxiety. My ascendance in the theater profession precisely coincided with my father’s precipitous decline. After his ignominious dismissal from McCarter Theatre he and my mother had spent a forlorn year on that farm outside of Princeton, departing only after my little sister was safely ensconced in college. In the next years, they moved a half dozen times, an itinerary that resembled the wanderings of Odysseus. Duplicating the precarious lifestyle of his younger days, my father pursued one pipe dream after another. He never lost his sunny positivism or his buoyant humor, but with every move his exploits became a little more quixotic. And through it all, with a poignant air of forced cheeriness, my mother remained his most ardent booster.

They first moved to Vermont, where Dad attempted to start a performing arts center in Brattleboro. When that failed, he tried selling Norwegian prefab kit homes to out-of-state buyers. When nothing came of that, Mom persuaded her brother, my wealthy Uncle Bronson, to buy an old Vermont farmhouse and hire Dad to restore it for resale. Next was Tampa, where Dad took a job as an artist-in-residence at the University of South Florida, with my mother on hand as an active faculty spouse. After that, the pair bounced back and forth between my brother’s and my sister’s hometowns of Amherst and Ithaca. During this stretch, Dad undertook his most fanciful project yet. Purely on spec, he created a long epic poem set during the Trojan War, written in the style of Homer’s

Iliad.

At all of his whistle-stops he landed temp teaching jobs, at schools like Cornell, U Mass, and Ithaca College, or directed student shows for their undergraduate theater groups. In each of these settings he was a popular and inspiring mentor, beloved by faculties and students alike. But he never stuck around for long.

My folks had reached their seventies by now. Their best days were drifting farther and farther into the past. They began to lose more and more of their old gang, those hard-drinking, hard-smoking bohemians from their younger years. My mother had fewer and fewer friends, and fewer and fewer people were around who remembered my father’s best work. With the burden of old age and nagging insecurity, Dad was growing increasingly fretful and prone to fatigue. But he and my mother kept moving on, moving on. Wanderlust never quite released them from its grip.

Meantime I was acting away on Broadway. I was loving my work, expanding my horizons, and making a bigger and bigger name for myself. But despite the pleasure and pride I took in my fat Broadway résumé, my concern and guilt at my parents’ increasing sense of dislocation weighed me down. Nor was this the only burden I carried during those frenetic years. Onstage I was a confident, respected actor, constantly employed and consistently in demand. But in my offstage existence, things couldn’t have been more different. By the time I reached the end of the 1970s, my personal life had come apart at the seams. All the verities of my first thirty years had utterly failed me. Every time I walked out a stage door I left the warm embrace of the theater and came up against the real world. In that world I was hanging on by a thread.

Adolescence

W

e all have to go through adolescence. If you’re lucky you go through it when you’re actually an adolescent. With me, it kicked in at thirty, about fifteen years late. For a compulsively good boy—a dutiful son, a committed husband, a doting father—my late adolescence was like a hair-raising ride on a runaway train. I clung for dear life to my seat on that train. There seemed to be no way to control its speed or direction. At a certain point I knew I was going to crash. I swung crazily between exhilaration, confusion, emotional exhaustion, and guilt. I was in an altered state of consciousness. I had no perspective. It would be years before I realized that the whole mess had been inevitable. The crash was long overdue, but it had to happen.

In distant hindsight, my life up to the age of thirty resembles a stately edifice, constructed over many years, only to be reduced to rubble in an instant. Emerging from a wildly unpredictable childhood, I had followed an orderly path. By its very nature, a theater career is

dis

orderly, but I had pursued mine with as much rationality and discipline as I could muster: a Harvard education, British academy training, rigorous work in rep theater, and success on Broadway. I had married at an absurdly young age, but my wife was resourceful and supportive, and our son didn’t arrive until we’d been married for a sensible six years. To all appearances we were a model family. So what was missing from this picture of happy domesticity?

Simply this: my adolescence.

In the theater, love and sex are occupational hazards. We actors are no more lovesick and libidinous than anybody else, but our working life is a chemistry lab of emotions and urges. It renders us uniquely susceptible. Let’s say two people are hired to portray two characters who fall in love. The two have never met. They are attached to other partners. At their first rehearsal, they don’t even appeal to each other all that much. But they set about to learn their lines and rehearse their scenes, always striving toward the closest possible imitation of the truth. In an atmosphere of erotic intimacy, the play begins to come to life in the rehearsal studio. A director with the intensity of Svengali does his damnedest to stir a mutual attraction between the two. They gradually discover seductive qualities in each other. They turn each other on. They start to hang out together after rehearsals in restaurants and bars. They think they are hiding their titillating secret from the rest of the cast, but in fact everyone else is on to them. On a night of giddy excitement, they open their play. The two act out their love relationship in front of hundreds of people. They touch the audience deeply. They are elated by their success. Somewhere around this time, they finally sleep together. Onstage, night after night, they go through the motions of their pretend passion. Offstage, their passion is genuine. They are madly in love. Their lives become a kind of ecstatic chaos. Eventually the magic begins to dissipate. Life’s complications begin to wear them down. The play itself begins to bore them. They break up. Long after the show closes, they both look back and wonder what in the world they had been thinking.

Is it any wonder there are so many affairs among actors? The miracle is that there are not many more.

I know whereof I speak. I acted in some twenty plays in and out of New York in the 1970s. In eight of them I had an affair with an actress in the cast. I staged a one-man sexual revolution, a dozen years after the actual sexual revolution had liberated my own generation. My backstage infidelities were dignified only slightly by the fact that they were, in a manner of speaking, serially monogamous: each time I would fall into an agony of love, replete with tears, longing, and late-night phone calls. Each time, my marriage would lose a little more tensile strength. Repeatedly I would feel on the brink of ending it and starting anew. Yet in each of these affairs, I had involved myself with a woman who was so enmeshed in her own relationship with someone else that there was no realistic possibility of my committing to her. Although I did not admit it to myself, this was probably a relief. It may even have been an unconscious choice. It allowed me to crawl back to my marriage, wallowing in a mire of confessional self-flagellation. It was Hickey’s dynamic, from

The Iceman Cometh

, but without the booze and the whores. Lacking the courage of my own concupiscence, I brought as much misery to my wife and my lover-of-the-moment as I had brought upon myself.

With the reckless passion, comical clumsiness, and destructive power of a rampaging elephant, I had finally reached my adolescence. But adolescence, too, comes to an end eventually. That runaway train goes too fast. It races out of control. Along comes one curve it can’t quite navigate. It crashes spectacularly. You survive the cataclysm, you crawl out of the wreckage, you wipe the blood from your face and check your limbs for broken bones. Then you stagger away from the crash site and get on with the rest of your life. For me, this was the story of the last few years of the 1970s.

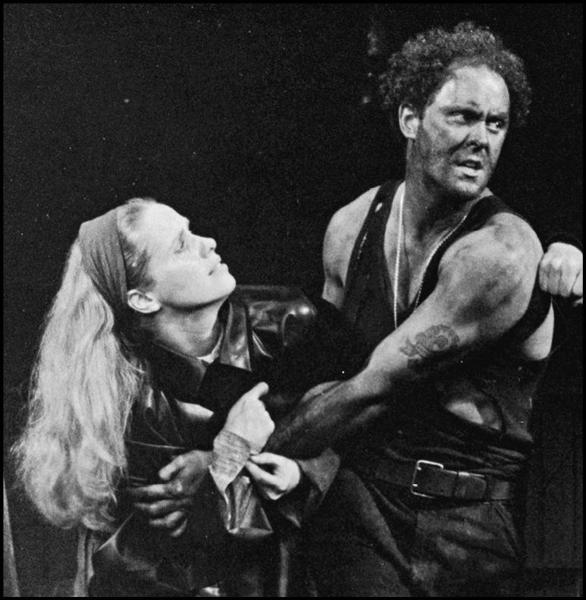

Photograph by Martha Swope. Courtesy Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

I

n 1977, Liv Ullmann was the most beautiful and celebrated film actress in the world. From her modest beginnings in the Norwegian town of Trondheim, she had risen to the status of an incandescent international star. She had played leading roles in several films of Ingmar Bergman, the great Swedish

auteur

. The naked intimacy of her performances in those films perfectly matched Bergman’s bleak vision of human emotion, spirituality, and sexuality. She was spoken of as Bergman’s muse. Their offscreen romantic attachment had ended a few years before, but it was still inextricably linked to the power of their collaborative work. She had most recently appeared in Bergman’s harrowing

Scenes from a Marriage

. In that film, it was impossible to imagine any other actress in the role Bergman had created for her. In her memoir

Changing

, published that same year, Liv fearlessly described the tortured passion between the two of them during their long affair. These passages read like scenes from a Bergman film. I was destined to reenact a few of those scenes myself.

One day in late spring 1977, I got a phone call from Alexander Cohen. Alex was one of the last great one-man Broadway producers, a throwback to a bygone era. A call from him was always good news. In his baritone growl, Alex said he wanted me to play Mat Burke opposite Liv Ullmann in

Anna Christie

on Broadway for the upcoming season. I knew next to nothing about either the role or the play, but I was elated at the offer. I dashed out to a bookstore, bought the play, and read it that very afternoon. My heart raced and my fingers trembled as I turned the pages. I was going to perform these scenes with Liv Ullmann!

My excitement was boundless, but underneath it another emotion began to stir. At the time, I had just extricated myself from my most recent ill-fated love affair. Jean and I had regained a measure of equilibrium and had once again resolved to make our marriage work. It was a cycle we had repeated two or three times in the preceding couple of years. As I read

Anna Christie

, my giddy anticipation was tempered by a sense of foreboding. This could be trouble. The cycle could start all over again. How could I prevent it? In the case of Liv Ullmann, I was already in love.

I met Liv at our first rehearsal. Sure enough, she cast a spell. In person she had a kind of heartbreaking beauty. No man in the room could take his eyes off her, nor any woman. She was a mix of playful and serious, vulnerable and tough, shy and daring. She disarmed us all with her earthiness and her willingness to be one of the gang. She was clearly accustomed to being treated like a queen, and yet she charmingly deflected everyone’s adulation. Her broad smile and ready laugh lit up the room. In the ensuing days, the work did not come easy for her. She had a regal bearing and a sensuous bloom of health that made her oddly ill-suited to the role of the downtrodden Anna, and with her heavy Nordic accent she struggled to master O’Neill’s yeasty slang. But she loved the high drama of José Quintero’s direction and she poured herself into the work. Watching her day by day, the whole cast became smitten with her. None more than I.

Prior to Broadway, we took the show out of town. Our first stop was Toronto. The production’s major players were put up at the Sutton Place Hotel. The company plunged into a week of tedious tech rehearsals at the Royal Alexandra Theatre. Outside of the gravitational pull of New York, Liv and I became closer and closer. We began spending all our time together, inside the playhouse and out. After our first Toronto performance, she invited the cast to celebrate with champagne in her dressing room. After twenty minutes, everyone began to peel off and say goodnight. Finally only Liv and I were left. The two of us sat alone in the room for another hour, laughing and talking in a thickening haze of drunkenness. Two or three times the stage-door man tapped on the door and asked us when we were going to leave and let him lock up. With too much champagne in us, we finally left the theater and climbed into the back of Liv’s car. Her impassive driver took us back to the Sutton Place Hotel. That night, the night we first performed

Anna Christie

, was the beginning of a year-long affair. Ever since that night, the Sutton Place Hotel has loomed in my mind as a grim landmark. It memorializes a moment shot through with a dizzying mix of joy, pain, and guilt, the first night of a year that changed everything.

By prior arrangement, Jean came up to Toronto a week later to join me for a short visit. She brought along five-year-old Ian. I had not told her about what had transpired between Liv and me. In a state of numb paralysis, I had done nothing to forestall her trip. The visit was horrific. On the very first night Jean was there, I blurted out to her the news of my latest infidelity. Her first response was incredulous laughter (“You’re kidding!”). This was quickly followed by bewilderment, then rage, and ultimately a kind of deranged despair. I was so choked with my own tears and guilt that I was blind to my unintended cruelty toward her. In retrospect it appalls me. There was plenty wrong with our marriage, but I’d had neither the honesty nor the courage to flatly state that I wanted it to end. Instead I blamed our troubles on some inexorable outside force that had me in its grip. How can we go on, I wailed, when I keep doing this to you? How can you endure it? I’m such a bastard! Why don’t you throw me out? The scene could have been scripted by Eugene O’Neill.

In essence that evening was the beginning of the end of our ten-year marriage. Jean flew home early with Ian, leaving me to grapple with a turbulent new reality of my own devising. The pre-Broadway tour continued for two more months. After Toronto we played Washington and Baltimore. The out-of-town run constituted a de facto separation from Jean and a de facto live-in relationship with Liv. Between Liv and me, passions ran so high that it was almost impossible to sort them out. We loved each other’s company, but from the very outset our relationship was beset with insecurity and strife. Following the age-old pattern of stage romances, the play had released a torrent of need in both of us. She longed for a simple love relationship, a safe haven from the unwanted glare of celebrity and star worship. In me she was looking for a strong and defiant protector. I was completely incapable of assuming that role. I was a tangled mass of conflict, woefully lacking in self-knowledge. On the one hand I was a horny teenager in a thirty-year-old body, grasping insatiably for all the sex I had never allowed myself. On the other, I was an escapee from an unhappy marriage and a defecting father, tortured with guilt and doubt. With such baggage, the affair was unlikely to be good for either of us, but this prevented neither of us from hurling ourselves into it. In the coming months, things only grew more troubled and intense. But by some miracle, despite all the tempestuous offstage drama of our relationship, the two of us managed to put on our costumes every night, walk out onstage, and

act.

As the weeks passed, more complications weighed on us. The backstage world of

Anna Christie

grew claustrophobic. It became the least fun show I’d ever been in. A subtle hierarchy took hold in the company, with Liv at the top. My friendships with three-fourths of the cast evaporated. Although Liv never invoked the privileges of stardom, an entourage gradually formed itself around her, answering to her every whim. It was comprised of our director, our company manager, Liv’s dresser, an older character actress in the cast, and their various traveling companions. Of this inner circle of fawning courtiers, I was the only heterosexual. I wrestled disconsolately with the role of royal consort. After every show the group would merrily carouse in a restaurant, striving mightily to flatter and entertain their queen bee. At the end of such evenings I would squire Liv back to her hotel room and leave the others behind. Everyone tacitly understood my courtly function. My male ego, fragile at the best of times, swung crazily between swaggering pride and cringing humiliation.