Eight Little Piggies (22 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

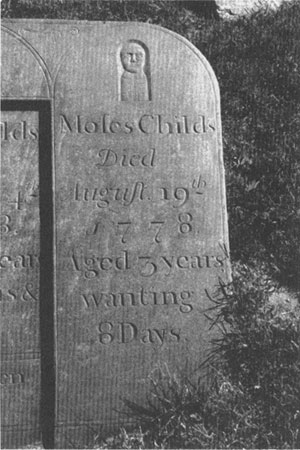

This lovely babe so young and fair

Call’d hence by early doom

Just came to show how sweet a flow’r

In Paradise would bloom.

The common gravestone for six children of Abijah and Sarah Childs. All died in an epidemic within one month.

Photograph by Deborah Gould

.

But bitterness sometimes breaks through. In a tiny cemetery on a windswept hill in Lower Island Cove, Newfoundland—a plot that also contains a monument for the four La Shana brothers lost at sea on May 25, 1883—I read of William Garland, who died in 1849 at age twenty-five:

Wherefore should I make my moan

Now the darling child is dead

He to rest is early gone

He to paradise is fled.

I shall go to him, but he

Never shall return to me.

The message is so simple, so commonplace, so often made—yet infinitely worth repetition in light of the curious human psychology that paints our past rosy by selective memory of the good. Koko burst this bubble in his “little list,” while another Gilbertian character, the sham-sensitive poet Reginald Bunthorne, understood the path of exploitation:

Tombstone of Moses Childs, youngest child to die.

Photograph by Deborah Gould

.

Of course you will pooh-pooh whatever’s fresh and new,

And declare it’s crude and mean,

For art stopped short in the cultivated court

Of the Empress Josephine.

A foolish or self-serving man like Bunthorne may make such an argument for realms of taste that admit no objective standard. But the directional, even the progressive, character of human knowledge and technology cannot be denied. Medicine, properly called the “youngest science” by Lewis Thomas, has not been among the most outstandingly successful of human institutions. Most improvements in longevity can be traced to a better understanding of nutrition and sanitation, not to any “cure” of disease. The germ theory of disease provided our one conspicuous triumph under conventional models of cure based on causal understanding, but more lives have been saved, even here, by prevention due to better sanitation, than by direct battle against bacteria. As for chronic conditions of aging and self-derailment—including most heart disease, strokes, and cancers—our success has been limited. Even so, and with all these strictures, modern medicine allows our children to grow up. The death of a child is now an unexpected tragedy, not a grim prediction. For this one transcendent reason alone, what sane person would choose any earlier time as a favored age for raising a family?

Technological progress is often less ambiguous and more linear. (I need hardly say that I define progress, in this sense, by internal standards of design and efficiency, not by resulting benefit to human life or planetary health. Technological progress will as likely do us in as raise us up.) If you need to get somewhere fast, airplanes beat horses, and if you need to rise, elevators are more pleasant than shank’s mare.

I have only one reason for taking up this old subject within a series of essays devoted to evolutionary biology. We evolutionists do hold a key to appreciating the universal (or at least the planetary) significance of this progressive potential in human technology. At least we know how bizarre and unusual such short-scale linearity must be in the history of our part of the cosmos. Human culture has introduced a new style of change to our planet, a form that Lamarck mistakenly advocated for biological evolution, but that does truly regulate cultural change—inheritance of acquired characters. Whatever we devise or improve in our lives, we pass directly to our offspring as machines and written instructions. Each generation can add, ameliorate, and pass on, thus imparting a progressive character to our technological artifacts.

Nature, being Darwinian, does not work in this progressive way with our bodies. Whatever we do by dint of strength to improve our minds and physiques—from the blacksmith’s big right arm in Lamarck’s Amanaesque metaphor to the accumulated knowledge of a modern computer wonk—confers no genetic advantage upon our offspring, who must learn these skills from scratch using the tools of cultural transmission.

This fundamental difference between Lamarckian and Darwinian styles of change explains why cultural transformation can be rapid and linear, while biological evolution has no intrinsic directionality and follows instead, and ever so much more slowly, the vagaries of adaptation to changing local environments.

Cultural transformation, in its Lamarckian mode, therefore unleashed a powerful new force upon the earth—producing all the ills of our current environmental crisis, and all the joys of our confidently growing children. But we should not scoff at poky, old, biological evolution, for this Darwinian style of change also placed a potent source of novelty into the cosmos.

By contrast, passage of time in the physical universe either lacks directionality (therefore excluding the essence of history, defined as a pattern of distinctive change imparting uniqueness to moments) or possesses only the longest-scale linearity of stellar burn-out or universal expansion from a big-bang dot. Our planet did not know the full richness of history until Darwinian change bowed in with the evolution of life.

I thought of this key distinction between physical and biological time as I searched for long, curving names in the cemetery of Middle Amana: Schuhmacher und Morgenstern—shoemaker and morning star; the human technologist vs. the planet Venus, bright in the sky just before dawn. And I remembered that Charles Darwin had drawn the very same contrast in the final lines of the

Origin of Species

. When asking himself, in one climactic paragraph, to define the essence of the difference between life and the inanimate cosmos, Darwin chose the directional character of evolution vs. the cyclic repeatability of our clockwork solar system:

There is grandeur in this view of life…. Whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Shoemaker vs. morning star.

I GREW UP

in New York and, beyond a ferry ride or two to Hoboken (scarcely qualifying as high adventure or rural solitude), never left the city before age ten. But I read about distant places of beauty and quiet, and longed to visit the American West. I fulfilled my dream during a family automobile trip at age fifteen. I remember my first views of Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Carlsbad Caverns. Yet, for reasons that I have never fathomed, my strongest memories of awe are reserved for the vast flatness of the Great Plains, for hundreds of miles of wheat and corn in Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Minnesota. I loved the symmetry of the fields, the endless flatness broken by Victorian farmhouses and their windbreaks of trees, the adjacent silos, the small towns marked by their signatures of water towers and grain elevators (the analog of church steeples for navigation in any old European village).

I feel no differently today. Two summers ago, I drove west with my family from Minneapolis, not on Interstate 90 (the enemy of regionalism), but on Route 14, with sidetrips to the lovely Victorian mainstreet of Pipestone, built of beautiful, soft red Sioux Falls quartzite, and to the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota. Only one town breaks the pattern of solitude and timelessness in 350 miles between Mankato, Minnesota, and the state capital of Pierre, South Dakota. Right on Route 14, midway between Sleepy Eye, Minnesota, and Blunt, South Dakota, stands De Smet, little town on the prairie, childhood home of Laura Ingalls Wilder.

The success of Wilder’s wonderful books about her pioneer childhood (I have read them all to my kids), not to mention the inevitable TV spinoff series, has converted De Smet into a commercial island (either desert or oasis according to your values) of hagiography. The main gift shop for Wilder paraphernalia sells an amazing array of items, from expensive furniture down to tiny bits of memorabilia at two bits a pop (bookmarks, pencils, cottonwood twigs from Pa’s trees). As testimony to our odd desire to possess, even in replica, some tangible property of a heroine or her bloodline, I was most amused by one of the twenty-five-cent items—the calling card of Laura’s daughter Rose (who became an ultraconservative journalist, an opponent of income taxes, social security, and all New Deal programs).

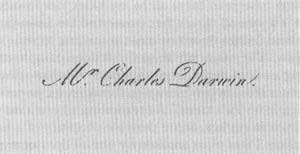

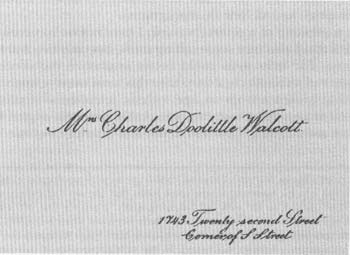

As something of a squirrel myself, I dare not be too critical. I confess that I also own some calling cards, but only two and both genuine. For what item could better symbolize the continual presence of an intellectual hero than this most overt testimony of personal presence from an age without telephones? I proudly own cards associated with two remarkable men who shared both a name and a calling: Charles Darwin and Charles Doolittle Walcott.

*

The calling cards of Mr. Charles Darwin and Mrs. Charles Doolittle Walcott.

The subject of calling cards, with its overt theme of personal greeting, inevitably raises the question of intellectual genealogy. If I actually own his card, how far back must I go to touch Charles Darwin? Since Darwin died more than one hundred years ago in 1882, a metaphorical handshake might seem so distant as to be uninteresting in contemplation. But intellectual genealogies tend to be surprisingly short since people of importance touch so many lives, and at least a few of the anointed will be blessed with great longevity. (True bloodlines, by contrast, tend to pass through many more generations in a given length of time both because children arrive early in life and because connections must pass through small numbers of progeny, often including no one with a long lifespan.)

In fact, I can touch Darwin through only two or three intermediaries. I studied vertebrate paleontology with Ned Colbert. Ned, as a young man, was the personal research assistant of Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History. I now touch Darwin either directly or by one more step, depending on which version of the most famous Osborn legend you endorse.

Osborn was a very smart man, but his immodesty greatly outran his considerable intelligence. He once published an entire book, dedicated to listing his publications and photographing his medals and degree certificates. (He cites, as a specious rationale in his forward, a simple and selfless desire to encourage young scientists by demonstrating the potential rewards of diligence.) Tales of Osborn’s smugness and arrogance continue to permeate the profession, more than fifty years after his death. The most famous story begins with W. K. Gregory, who took over Osborn’s course in vertebrate paleontology after the great man retired. Once a year, Gregory would take his students to visit the haughty professor emeritus. At one such meeting, Osborn rose from his desk and stiffly shook each student’s hand. An interlude of increasingly uncomfortable silence followed, for no one knew how to address a person of such eminence. Osborn himself finally broke the silence, saying: “When I was a young man about your age, I worked for a year in the laboratory of E. Ray Lankester in London—and one day Charles Darwin [T. H. Huxley, in the other version] walked in—and I shook his hand, so I know how you all feel now.” Thus, my short linkage to Darwin needs only two or three steps—either Colbert-Osborn-Darwin or Colbert-Osborn-Huxley-Darwin.

Walcott (1850–1927), my other Caroline hero, may not be so well known, but he ranks as a giant within my profession of paleontology. Charles Doolittle Walcott was the world’s greatest expert on rocks and fossils of the Cambrian period—the crucial time, beginning some 550 million years ago, when modern multicellular life first arose in a geological whoosh (a few million years) called the “Cambrian explosion.” Walcott, a master administrator, was also the most powerful man in American science during his prime. In 1907, he moved from head of the United States Geological Survey to secretary (their name for boss) of the Smithsonian Institution, where he died with his boots on in 1927. He persuaded Andrew Carnegie to found the Carnegie Institute of Washington and encouraged Woodrow Wilson to establish the National Research Council. He was an intimate of every president from Teddy Roosevelt to Calvin Coolidge. In 1920, at age seventy, he made the following entry in the yearly summation at the end of his diary:

I am now Secretary of Smithsonian Institution, President National Academy of Sciences, Vice Chairman National Research Council, Chairman Executive Committee Carnegie Institute of Washington, Chairman National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics…. Too much but it is difficult to get out when once thoroughly immersed in the work of any organization.

As a deeply traditional and conservative doer and thinker, Walcott suffered the unkind fate of many people who hold immense power in their times, but do not pass innovative ideas along to posterity—erasure from explicit memory, despite endurance of unrecognized influence. Few outside the profession of paleontology may remember Walcott’s name today, but no scientist has exceeded his power and prestige.

Since discoveries tend to outlive personalities, Walcott’s name has survived best in attachment to his most enduring single accomplishment—his remarkable find, lucky in Pasteur’s sense of fortune favoring the prepared mind, of the world’s most important fossils, the animals of the Burgess Shale (see my book,

Wonderful Life

). In 1909, high in the Canadian Rockies, Walcott discovered the closest object to a holy grail in paleontology—a fauna blessed with complete representation, thanks to the rare preservation of soft anatomy, from the most crucial of all times, right after the Cambrian explosion.

Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, Walcott then proceeded to misinterpret these magnificent fossils in the deepest possible way. He managed to shoehorn every single Burgess species into a modern group, calling some worms, others arthropods, still others jellyfish. The Burgess animals became a small group of simple, primitive precursors for later, successful lineages. Under such an interpretation, life began in primordial simplicity and moved inexorably, predictably onward to more and better.

Walcott’s reading, originally published in 1911 and 1912, went virtually unchallenged for more than half a century. But during the past twenty years, an elegant and comprehensive recollection and restudy by Harry Whittington and his students has entirely reversed Walcott’s interpretation. Burgess diversity—in range of anatomical designs, not number of species—exceeded the scope of all organisms living today. The history of life is therefore a story of decimation and limited survival (with enormous success to a few of the victors, insects for example), not a tale of steady progress and expansion. Moreover, we have no evidence that survivors prevailed for any conventional cause rooted in anatomical superiority or ecological adaptation. We must entertain the strong suspicion that this early decimation worked more as a grand-scale lottery than a race with victory to the swift and powerful. If so, then any rerun of life’s tape would yield an entirely different set of survivors. Since

Pikaia

, the first recorded member of our own lineage (Chordata), lived as a rare component of the Burgess fauna, most replays would not include the survival of our ancestry—and we would be wiped out of history. Conscious life on earth is this tenuous, this accidental.

I regard this reinterpretation of the Burgess Shale as the most important paleontological conclusion of my lifetime. If you accept my judgment on the importance of the Burgess Shale, then Charles Doolittle Walcott must join the roster of great scientists who achieved both power in their own time and immortality later. Whatever his interpretation, no one can take away his discovery.

But why did Walcott so thoroughly misinterpret his most important fossils? I suggested two basic reasons in a long chapter of my recent book,

Wonderful Life

. First, and however mundane the point, Walcott was so insanely busy with administrative tasks that he never had time for adequate study of the Burgess animals. His papers of 1911 and 1912 were only meant as preliminary accounts, but he never wrote the main act. (He had zealously—and jealously—guarded the Burgess fossils for a grand retirement project, but died in office at age seventy-seven.) Even if Walcott had been intellectually inclined to let the Burgess fossils tell him their amazingly unconventional story, he never found time for a proper conversation. Testimonies to Walcott’s lifestyle abound in the Smithsonian archives, but I found no document more poignant than the following statement submitted to his bank:

I enclose herewith the affidavit that you wish. I used to sign my name Chas. D. Walcott. I now use only the initials, as I find it takes too much time to add in the extra letters when there is a large number of papers or letters to be signed.

Second, and more importantly, I do not think that Walcott was inclined to free and open conversation with the Burgess fossils. I don’t accuse him of biases stronger than those of most scientists; I merely say that we all live within our own constraining world of concepts, and that the historical record grants us insight into the scope and power of Walcott’s preconceptions. Walcott, from the depths of his traditionalism, was fiercely committed to a view of life’s history as predictably progressive and culminating in the ordained appearance of human intelligence. As a Christian evolutionist, he believed that God had established the law of natural selection expressly to produce this intended result in the long run. At the height of controversy with fundamentalism in the days of Bryan and the Scopes trial, Walcott rejected the usual view (held by both scientists and theologians then and now) that science and religion occupy separate intellectual spheres demanding equal respect. He held instead that science must validate a “correct” view of divine guidance through the immensity of geological time in order to avoid accusations of atheism. Walcott therefore authored an appeal, signed and published in 1923, a year before Scopes was indicted in Tennessee. Endorsed by “a number of conservative scientific men and clergymen” (including Herbert Hoover and Henry Fairfield Osborn of my introduction), this statement held, in part:

It is a sublime conception of God which is furnished by science, and one wholly consonant with the highest ideals of religion, when it represents Him as revealing Himself through countless ages in the development of the earth as an abode for man and in the age-long inbreathing of life into its constituent matter, culminating in man with his spiritual nature and all his God-like power.