Eight Little Piggies (31 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

DID YOU EVER WONDER

what happens to old automobile tires? Since the United States boasts almost as many vehicles as people, our nation may feature nearly twice as many wheels as feet, and therefore (depending upon the Imelda Marcos factor of pairs per person) more tires than shoes. Well, I don’t know what happens to our discarded wheel wear, but I do know the fate of many worn tires in third-world nations. They are cut apart and made into the soles and straps of sandals (I own pairs purchased in the open-air markets of three continents—Quito, Nairobi, and Delhi).

In our world of material wealth, where so many broken items are thrown away because the cost of repair now exceeds the price of replacement, we forget that most of the world fixes everything and discards nothing. (Streets in crowded Indian cities, contrary to our usual assumptions, are often spotlessly clean because any item has value in reuse or resale. Scraps of paper are immediately scavenged; even cow pies remain on the street for only a few seconds before they are collected for fuel and slapped against a wall to dry.) I have never visited a place more fascinating than the recycling market of Nairobi—a true testimony to human ingenuity. Here sandals are made from tires, bracelets from telephone wire, kerosene lamps from bisected tin cans, containers from scraps of metal, and cooking pots from the tops of oil drums.

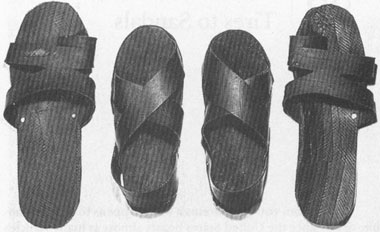

Two pairs of sandals made from recycled automobile tires. I bought the large pair at a street market in Delhi, India, and the smaller pair at the recycling market of Nairobi, Kenya.

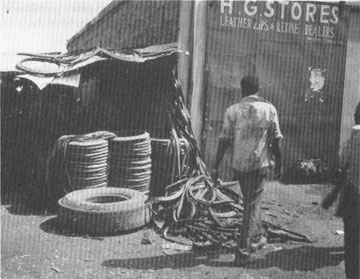

Tire strips cut for sandals at the recycling market of Nairobi.

This little prologue may strike you as interesting enough, but dubiously related to the intended subject of this essay—evolution and the history of life. Yet the theme of recycling for purposes almost comically different from original intent not only occupies a central place in the history of life but also completes an argument that I left half-finished in the previous essay. The last piece examined Darwin’s justification for predictable progress in the history of life and argued that recent discoveries about the frequency, rapidity, and extent of mass extinction suggest a much more quirky and uncertain path. I pointed out that Darwin did not locate the source of progress in the basic mechanics of natural selection itself—for he recognized natural selection as a theory of local adaptation only, not a statement about general advance. He justified progress with another argument about nature embodied in his favorite metaphor of the wedge. Nature is chock-full of species (like a surface covered with wedges) all struggling for a bit of limited space. New species usually win an address by driving out others in overt competition (a process that Darwin often described in his notebooks as “wedging”). This constant battle and conquest provides a rationale for progress, since victors, on average, may secure their success by general superiority in design.

Sandal salesmen at a street market in Delhi.

I argued that mass extinction prevents wedging from establishing long-term patterns in the history of life. Progress by competition may occur in normal times, but episodes of mass extinction undo, disrupt, and redirect this process so frequently that wedging cannot put a dominant stamp upon the overall course of life. I do not believe that mass extinctions work with absolute randomness, treating each species as a coin to be flipped or a die to be rolled. Survivors probably prevail for reasons, but here’s the rub (and the role for the wheel of fortune): The rules for survival change in these extraordinary episodes, and features that help species to prevail through catastrophes need not be the sources of success in normal times. Getting through a mass extinction may require a stroke of fortune in the following special sense: A feature evolved for one function in the wedging of normal times must, by good luck and for different reasons, provide a crucial benefit under the different rules of episodic catastrophe. (The diatoms of Essay 21, the only group of planktonic microorganisms to sail through the Cretaceous debacle, had evolved a life cycle with a dormant stage in order to weather predictable seasonal fluctuations of light and nutrients in normal times. If an impacting comet entrained a dust cloud that darkened the earth for several months, the survival of diatoms might be linked to a capacity for dormancy evolved for quite different reasons. Mammals may have prevailed, in large part, by virtue of small body size. But we can hardly label limited size as a preparation for long-term success or even as an active adaptation at all. Mammals may have remained small for primarily negative reasons—because dinosaurs dominated the ecospace of large creatures, and mammals could not displace them by wedging in normal times.) Thus, mass extinction sets a quirky and interesting course for life by opening opportunities to new groups and by basing success upon fortuitous side consequences of features evolved for other reasons. Who cares how well a tire works when the rules change and we run out of gas; continued existence now depends upon a fortuitous capacity for conversion to some other, utterly unanticipated role—retreading for sandals, for example.

But this argument—as far as I went in Essay 21—grants the wheel of fortune only half a loaf. For any champion of the wedge will swiftly reply: Mass extinction is a negative force. It makes nothing and can only pick and choose among creatures fashioned by natural selection. Sure, mass extinction can disrupt a trend, wipe out a complex group, or send life down an unpredicted channel—but evolution is about making, not about differential removal. The creative force in evolution, the motor of construction, must still reside in the processes of normal times, building creatures that will one day pass for review before the sieve of mass extinction. And the controlling process of normal times is wedging by competition.

I could rebut this argument in several ways. I might argue, for example, that sorting by differential death in mass extinction mimics, on a grander scale, the ordinary mode of operation for natural selection in normal times. Natural selection is a sieve, not a sculptor. Many are called; few are chosen. Natural selection is powered by differential birth and death; the few survivors accumulate and intensify their favorable features bit by bit on the relentless sieve of each generation. What is mass extinction but a grander sieve, sorting out species rather than organisms. If the sorting of organisms in normal times yields change that we label as positive, why not grant the same status to differential death in episodic catastrophes? Mass extinction need not be viewed as a negative force opposed to progress in normal times.

But I would choose an opposite tack to provide the other half-loaf to the wheel of fortune. Rather than promoting the wheel of mass extinction by its formal similarity to processes at smaller scale, I would proceed in the reverse direction. I will argue, in short, that the fundamental principle of quirky and unpredictable success by fortuitous side consequences pervades all scales. This vital principle of the wheel does not “click in” only at global catastrophe, leaving most of time to the wedge of ordered progress. The tires-to-sandals principle works at all scales and times, interacting with the wedge to permit odd and unpredictable initiatives at any moment—to make nature as inventive as the cleverest person who ever pondered the potential of a junkyard in Nairobi.

I will go further and make a statement that may seem paradoxical. The wedge of competition has been, ever since Darwin, the canonical argument for progress in normal times. I claim that the wheel of quirky and unpredictable functional shift (the tires-to-sandals principle) is the major source of what we call progress at all scales. Advance in complexity, improvement in design, may be mediated by the wedge up to a certain and limited point, but long-term success requires feinting and lateral motion, with each zig permitting another increment of advance, and progress crucially dependent upon the availability of new channels. Evolution is an obstacle course not a freeway; the correct analogue for long-term success is a distant punt receiver evading legions of would-be tacklers in an oddly zigzagged path toward a goal, not a horse thundering down the flat.

Let us take the broadest possible look at just three prerequisites for continuity in the sequence that, in our parochialism, we view as the crucial and representative case of evolutionary advance—the origin of human consciousness. At each true turning point, each leap in the capacity for substantial advance, we meet the wheel spinning its way toward a new use for old features (sandals from tires); the wedge can only promote, for a limited time and extent, what the wheel makes possible.

1.

Origin of the genetic flexibility for major advance in complexity

. For evolutionists, perhaps the most intriguing and unexpected discovery of molecular genetics emerged during the 1960s when study after study proved that, in multicellular organisms, only a small percentage of the total genetic material consists of functional genes in single copies. Most of the genetic material may be “junk” with respect to information needed to build and maintain a working body. Moreover, many genes exist in multiple copies for obscure reasons unrelated to the necessary functions of bodies.

Nonetheless, it soon became clear to evolutionists that redundancy of multiple copies might be

the

crucial prerequisite for evolution of complexity. Suppose that the original unicellular ancestor of all complex creatures had only one copy of each gene and that each gene coded for a vital function. (This claim is not mere conjecture, but represents the actual state of the simplest creatures alive today and the best models for ultimate multicellular ancestors.) These creatures work very well; they may be honed to an optimum by natural selection, shorn of all unneeded fat and flab. But now, a conundrum for evolution: These creatures may excite our admiration for efficiency, but how can they change in the crucial sense of adding new capacities in complexity? Each gene codes for something vital; it can only alter by improvement in its own channel. This kind of genetic system offers no flexibility, no play, no capacity for adding something truly new.

This conundrum led evolutionists to grasp the fundamental role of multiple copies in permitting the evolution of complexity. If genes exist in several copies, but only one supplies the body’s functional need, then the other copies are free to experiment, vary, and add capacity through occasional good fortune.

Well and good so far, but we now face a logical puzzle: Unless we thoroughly misunderstand the fundamental nature of causality, multiple copies cannot arise “for” their potential use in permitting complexity millions of years in the future. Multiple copies are the key to complexity, but they must have evolved for other reasons—the tires-to-sandals principle of quirky functional shift.

This case is particularly interesting because the initial reason for duplication (harvesting of rubber for tires) may not, itself, have much to do with natural selection as traditionally conceived in terms of organisms struggling for reproductive success. Duplication may arise by selection at the lower level of genes, a process invisible in the larger world of the wedge. Genes also play the game of natural selection in their own realm, and those that develop the capacity to duplicate and move (transposons, or jumping genes) secure advantages at this lower level, just as organisms win in Darwin’s world by leaving more surviving offspring. In fact, gene duplication may be abetted by producing no effect upon bodies, for invisibility at Darwin’s level of the wedge provides hiding space and assures that no negative pressures of natural selection shall impede the accumulation of “unneeded” extra copies. Yet these “redundant” duplicate genes may house the latent source of later complexity.