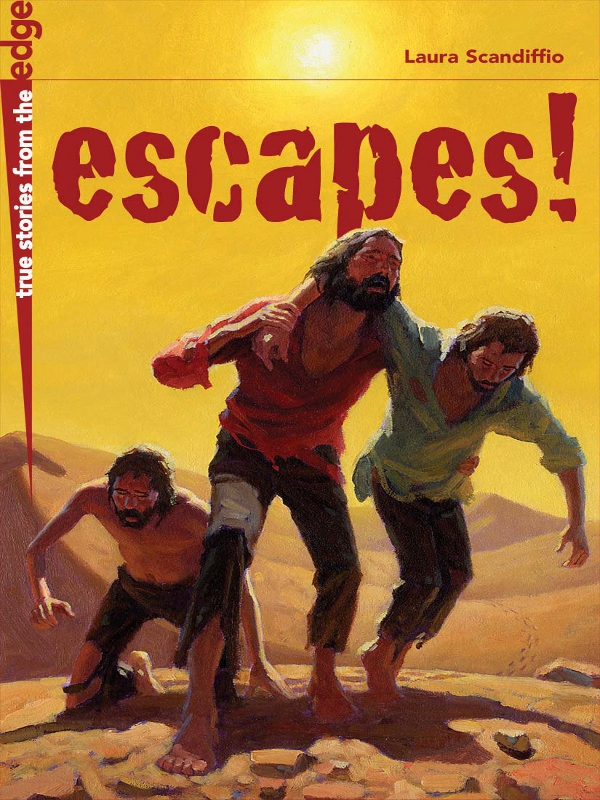

Escapes!

Contents

“From here there is no escape...”

Struggles for Freedom

A

SLAVE, CHAINS ON HER ANKLES AND WRISTS,

is tugged to the auction block. A man sent to prison for his beliefs watches his guard close the cell door and fears that he has seen daylight for the last time. A soldier, hands on his head, is marched at gunpoint through the grim gates of his enemy's prisoner of war camp.

All very different people, from different times and places, and all dreaming of the same thing â

Escape!

It's an impulse every human being feels when trapped. No one is willingly confined, and every captive dreams of freedom. A special few will act on this slim hope.

Men and women have used their wits and courage to escape from all sorts of threats: from slave owners, from dungeons, from enemy armies, from physical danger. They may be fleeing jailers or governments. Some have been shut in by four walls, while other prisons are the kind you can't touch, but which trap people alive â in slavery or oppression.

The greater the obstacles to be overcome, the more impossible escape seems, the more the stories fascinate us. Across the ages, different places have come to mind as the ultimate challenges for escapers. Each era has had its notorious prisons â from England's Tower of London, where people who posed a threat to the government awaited execution, to France's Bastille, where inmates could be locked away their whole lives without a trial. Slavery â whether in ancient Rome or in many of the American states during the 1800s â was a fate millions dreamed of fleeing. The prisoner of war camps of the Second World War (1939â45), with their barbed wire, armed guards, and spotlights, seemed inescapable to all but a determined few. And the “Cold War” that followed, between the Soviet Union and the Western powers, brought with it the infamous East German border wall, which kept all but the most desperate defectors behind its barrier of concrete, mines, and armed patrols with orders to shoot.

And yet despite the odds, a few found ways past these deadly traps, ways that show the amazing range of human creativity. They got out with clever disguises or ingenious hiding places; by patiently waiting or boldly dashing forward; by using whatever materials were at hand, crafting tools of escape from even the most innocent-looking objects.

“I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person now I was free.

There was such a glory over everything, the sun came like gold through

the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in heaven.”

Harriet Tubman, an American slave who escaped from her master in 1849, remembered her first thrilling taste of freedom. Her reaction is surprisingly similar to the feelings recalled by other escapers, whatever the place and time. Many speak of the same exhilarating moment when, though they could scarcely believe it, they were actually free.

Once Harriet Tubman made it north to freedom she wasn't content to stay there, however. Despite the dangers, she returned south again and again to help other slaves escape, more than three hundred in all. She became part of the network of antislavery helpers known as the Underground Railroad, people who hid runaway slaves on their journeys north out of the slave states, often all the way to Canada.

Still, escape from the slave states was no easy matter. Often thousands of miles had to be crossed, with professional slave catchers close on runaways' trails. But until the Emancipation Proclamation freed all slaves in 1863, many were desperate enough to try. One slave even had friends package him inside a wooden box, three feet by two feet, and mail him to the state of Pennsylvania, where slavery was illegal. He spent 27 hours inside, and no one paid much attention to the label: This Side Up, With Care. Amazingly, he survived, and Underground Railroad workers unpacked Henry “Box” Brown, as he became known, in Philadelphia.

Some people have managed to escape all on their own, without aid, but many others could not have been successful without the bravery of secret helpers on the outside. The Underground Railroad was the most famous of such networks in the 1800s. A hundred years later, the Second World War saw the birth of secret organizations dedicated to helping Allied soldiers escape or evade capture by the enemy.

“It is every officer's duty to escape...”

An Allied combat pilot of the Second World War faced huge risks every time he climbed into the cockpit. If shot down, he hoped to bail out and parachute to safety. But even if he survived the landing his troubles were only beginning. His mission had probably taken him far over enemy territory â maybe Germany or occupied France. Chances were he'd been spotted on the way down, and enemy soldiers were already rushing to take him prisoner.

Military intelligence in England realized how critical it was to get these pilots, as well as the soldiers stuck in prisoner of war (POW) camps, back into action. A new branch of the British Secret Intelligence Service â dubbed MI9 â was formed. Its job was to do everything possible to keep downed pilots out of enemy hands and to help prisoners of war to escape. Working round-the-clock, the people at MI9 came up with gadgets and schemes to stay ahead of the enemy. The “science” of escape was born.

One unconventional technical officer at MI9, named Christopher Clayton-Hutton, realized that many escape tricks had already been discovered â by the soldiers of the First World War. Clayton-Hutton recruited schoolboys to read memoirs from World War I for clues to what a soldier needed in order to escape. He was impressed by the boys' work. Many of the ingenious escape methods of the previous war had been forgotten.

Clayton-Hutton scanned the boys' list of escape aids, and came across “dyes, wire, needles, copying paper, saws, and a dozen other items, some of which I should never have dreamed of.”

He set to work on an “escape kit” that every pilot could carry in the front trouser pocket of his uniform and that held essentials to keeping him at liberty: compass, matches, needle and thread, razor, and soap (looking grubby was a sure giveaway when you were on the run!). Food was provided in small, concentrated form: malted milk tablets or toffee.

MI9 also wracked its brains to help prisoners of war escape their German camps. Getting out was hard enough, but once outside a crucial item was needed if they hoped to stay free â a map. Escaping POWs hoped to cross the German border into Switzerland, a country that had remained neutral in the war. From there they could make contact with helpers and get home.

But without a map, they were more likely to be recaptured while wandering near the border, lost. And it couldn't be just any old map. It had to open without rustling (escapers often consulted maps while search parties were combing the area nearby), and it had to be readable even when wet, and no matter how many times it was folded and creased. MI9 hit upon the solution: reproduce maps on silk.

But how would they get them to the prisoners? All POWs received mail from home, so MI9 came up with ways to sneak the maps in through letters and packages from “relatives.” Working with the music company HMV, they inserted thin maps inside records, which would be sent to prisoners by nonexistent aunts.

As the war continued, MI9's tricks got cleverer. POWs were sent blankets that, once washed, revealed a sewing pattern that could be cut and stitched to make a German-looking jacket â a perfect disguise. The razor company Gillette helped to make magnetized razor blades that worked as compasses. Wires that cut bars were smuggled in shoelaces, screwdrivers inside cricket bats.

The stories of the lucky Allied soldiers who escaped from Germany were kept secret for many years, and important details were changed in or left out of books published after the war. Many people feared that a new war with the Soviet Union was on the horizon, and it would be foolish to give away escape tricks and routes that might prove useful during the Cold War. After all, a known escape trick is a useless one.

It was the Cold War that gave rise to one of the most famous symbols of imprisonment, and of the dream of escape: Germany's Berlin Wall. This concrete barrier, topped with barbed wire and dotted with watchtowers and arc lamps, was begun by the Communist government of East Germany in 1961 to halt the flow of thousands of citizens defecting to West Germany. Soon the entire country was split in two by the border wall. In East Berlin some people could look out their apartment windows and see into the homes of West Berliners living on the other side. And yet they were completely cut off from one another. As one border guard put it, even though the other side “was only six or seven meters away I would never go there. It would have been easier to go to the moon. The moon was closer.”

Although many residents of East Germany accepted their government and living conditions, others found they could not. Freedom â the freedom to travel, to say and write what they believed without fear of punishment â beckoned. Until the wall was torn down in 1989, countless escapes were attempted at the wall, and many died trying to get across it to the West. They tried climbing over it, tunneling under it, driving past it hidden in the cars of West Germans. Once again, it seemed that the bigger the obstacle placed between a person and freedom, the more human creativity is inspired to meet the challenge.