Financial Markets Operations Management (38 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

Corporate Actions

A corporate action is an event usually initiated by the issuer of the securities (mainly equities but also, to a lesser extent, bonds) and sometimes by a third party. A corporate action can result either in a financial impact on the shareholders or bondholders or on the capital structure of the issuer itself.

There are many different types of corporate action event; the exact number is difficult to calculate. Nevertheless, corporate actions can be grouped into nine event-type categories with numerous sub-types. You will find a list of these categories in Appendix 11.1 at the end of this chapter.

The key relationship has always been between the issuer and the investor. This was certainly true in the days when investors owning registered securities (typically equities) would have their names recorded on the issuer's shareholder register. In today's world, and especially where investors own international securities, this one-on-one relationship is less frequent, as there are a number of intermediaries acting on behalf of both issuer and investor. We will identify these intermediaries and examine their roles and responsibilities in this chapter.

Each and every type of corporate action event requires one or more actions to be taken. For the purposes of this book, we will concentrate on only a few of the more usual types of event. Depending on the type of event, the actions required can and do differ in detail; however, we can summarise the actions that are required into the following types:

- Information from issuer;

- Communication to investor;

- Decision to be made/no decision required by investor;

- Conclusion with results debited or credited to the investor's account.

These four actions apply in the vast majority of events.

In November 2001, the Giovannini Group published a report entitled

Cross-Border Clearing and Settlement Arrangements in the European Union

in which a number of barriers to

efficient cross-border clearing and settlement were noted.

1

In particular, corporate actions were discussed in Barrier 3: “Differences in national rules relating to corporate actions, beneficial ownership and custody” (see below).

By the end of this chapter you will:

- Understand the complexities of corporate action events;

- Understand the event processing and information flows;

- Know the operational risks involved;

- Appreciate the changes within the industry;

- Understand the impact of corporate actions on other departments.

We can consider corporate action events from two perspectives: those that are voluntary or mandatory and those that are predictable or unpredictable (announced).

Corporate action events can either be voluntary or mandatory. From the shareholder's point of view, a voluntary event is where the shareholder has the option to participate in the event.

By contrast, a mandatory event is where the shareholder has no option but to participate in the event. Please note that a voluntary event for the issuer could very well be a mandatory event for the investor.

A predictable event is one where the security has one or more events that will be known from the time that security is first issued. An announced event is one where, in most circumstances, the issuer decides to take action in some form or another.

All events will be a combination of both of the above perspectives; so, for example, a redemption on a state bond will be mandatory and predictable. A bonus issue, on the other hand, will be mandatory and announced. For corporate actions staff, the most risky combination will usually be announced and voluntary, mainly because someone, either the investor or its intermediary, has to make a decision as to what action to take. A decision that is either missed or submitted late will not be executed by the issuer's agent.

In Appendix 11.2, you will find a list of voluntary and mandatory events for both equities and bonds.

The two key participants in any corporate action event are the issuer and the investor (or the investor's agent, such as a fund manager). As we have seen above, it is unlikely, although not impossible, that the issuer will communicate directly with the investor. Instead, the issuer communicates via a chain of intermediaries. These intermediaries include the following:

- Fund manager;

- Global custodian;

- Local/sub-custodian;

- Local central securities depository;

- International central securities depository;

- Data vendors;

- Receiving/paying agent.

Fund managers act on behalf of their clients as regards corporate action events as well as managing their assets. It is the fund manager, rather than the client, who decides what action to take where the event is voluntary in nature (e.g. where an issuer announces a rights issue).

Whether the global custodian's client is the institutional investor or the fund manager, its role is to act as an information taker (from the sub-custodian) and information giver (to the fund manager) plus decision taker (from the fund manager) and decision giver (to the sub-custodian). The global custodian has the responsibility of ensuring that the results of any corporate action

event (whether voluntary or mandatory) are correctly actioned and recorded. The global custodian is very dependent on its sub-custodian for much of the information/decisions/results flows and, as a control, will verify any corporate actions information that has been published.

Typically, a local bank can act in both capacities depending on the type of client. The roles and responsibilities mirror those of the global custodian (i.e. information/decisions/results flows), with the difference being that the custodian is located in the market where the issuer's securities are listed. This makes the local/sub-custodian much closer to the market than the global custodian would be.

It is usual for the local CSD to hold the entire issue of any eligible security on behalf of the beneficial owner. (Remember that there will be a local sub-custodian/global custodian chain or a local custodian as intermediary between the CSD and beneficial owner.) The issuer's agent will communicate with the CSD.

The ICSDs, Euroclear Bank (EB) and Clearstream Banking Luxembourg (CBL), hold their participants' securities in one of three ways, depending on the type of security:

- Each ICSD will have appointed a specialised depository that holds securities for one or other of the ICSDs. There are, therefore, two SDs in this case.

- Both ICSDs jointly appoint a common depository that holds the entire issue to the order of EB and CBL. The CD therefore has only two clients for each issue held.

- Each ICSD has a participant custody account with some, but not all, local CSDs.

Data vendors will also be recipients of information broadcast by the issuers. In addition to corporate actions information, the data vendors provide pricing information and information on companies and securities.

Examples of data vendors include Bloomberg, Markit, Morningstar, SIX Financial Information, Sungard and Thomson Reuters. You can find more details on the Software and Information Industry Association's Financial Information Services Division at

www.siia.net

.

Typically a bank, a receiving/paying agent is appointed by an issuer to make periodic cash payments (dividends, coupons and bond redemption proceeds) to the issuer's investors and receive payments for relevant corporate action events such as rights issues.

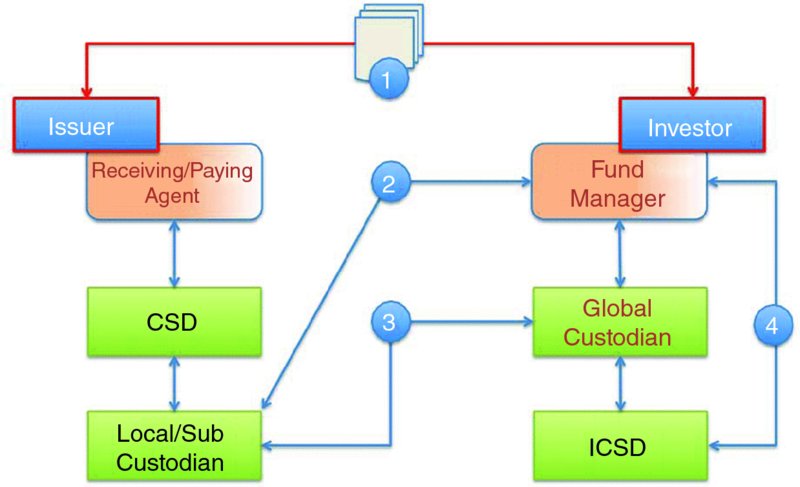

Depending on the exact types of relationships, the chains of communication can best be described in the manner shown in

Figure 11.1

.

This represents the origin of any corporate action where the issuer communicates directly with the investor. The investor submits its decisions, where required, direct to the issuer.

It is more usual in today's environment for intermediaries to act on behalf of the issuer and investor; in which case:

- In a domestic situation, the issuer communicates through its agent to the local central securities depository, from there to a local custodian and finally to the investor's fund manager.

- In a foreign situation, the issuer communicates in much the same way as in 2 above, except that the local custodian now acts as the global custodian's sub-custodian. The global custodian communicates with its client's fund manager.

- If the fund manager is a direct participant in one of the two international central securities depositories, communication takes place between the fund manager and the ICSDs. If not, it is the global custodian that is the participant in one of the ICSDs and communication flows accordingly.

FIGURE 11.1

Communication chains between issuer and investor

We will look at information flows in more detail in Section 11.6.

With any corporate action event, one of the first tasks is to establish who is entitled to benefit from the event. If we consider an asset class such as equity/shares, this will not normally be a problem, as the following example demonstrates.

An investor purchased 50,000 registered shares several weeks ago and the purchase settled on the intended settlement date. Within a very short period of time these shares would have been registered in either the investor's name or in the name of the appropriate nominee. The

issuer will know that this investor's name will be on its shareholder register. Today, the issuer announces a corporate action event, for example, a cash dividend.

Who, then, is entitled to receive this cash dividend? It will be the investor for the following two reasons:

- When the investor made the original purchase, it was implied in the contract that the purchase was made cum-dividend (“cum” is from the Latin “with”). On the assumption that the investor was still the owner of the shares, then he would be fully entitled to the dividend on the 50,000 shares.

- Once the 50,000 shares were registered in the investor's name (i.e. noted on the shareholder register) then the investor was the legal owner of the shares and thus entitled to receive the cash dividend.

A complication arises, however, in the situation where the investor makes a purchase and, for whatever reason, the shares are not on the shareholder register in time. The issuer will pay the dividend to whoever's name is on the shareholder register; in this case, the purchaser will not receive the dividend even though the purchase was made cum-dividend. Who, then, will receive this dividend? As the dividend is paid to whoever's name is on the register, the dividend will actually be paid to the seller of the shares rather than the purchaser (the investor).

For this reason there needs to be a mechanism by which the correct entity is not only entitled to receive the benefit but receives the benefit in actuality. This is how it works. The shareholder register is a dynamic document, in that buyers and sellers are continuously having their names added to and removed from the register. As the issuer can only pay a dividend to those named on the register, you can perhaps appreciate that on a very busy register it becomes very difficult to identify the true beneficiaries. For this reason, the issuer will close the register on one particular date. This date is known as the

record date

(also known as the

books close date

). Once the register has been closed, the dividend is paid to the name(s) on the register at that time. As before, this will correctly identify the beneficiaries.

But we still have a problem. An investor may have purchased shares only a few days before the record date. In this situation it is unlikely that the transaction would even have settled, let alone have the purchaser's name added to the register. To overcome this problem, the local stock exchange will declare an

ex-dividend date

that occurs shortly before the record date (“ex” from the Latin “without”). How many days before depends on the local settlement convention. It is usually one day less than the number of days between the trade date and the intended settlement date. If the settlement convention is

T

+3, then the number of days between the ex-dividend date and the record date is two.

We can look at this another way â the investor needs to purchase shares just before the record date to be sure of qualifying for the dividend payment. In the above example of a

T

+3 settlement cycle, three days are needed before the shareholder's name goes on the register (i.e. the day before the ex-dividend date).

What, then, happens on the ex-dividend date? Firstly, on the ex-dividend date, the share price will drop by the amount of the dividend compared with the previous day (

ceteris paribus

). Secondly, the shares will trade ex-dividend and published price lists and broker contract notes will be flagged with an “xd” tag after the price. This emphasises that the shares are being bought without any entitlement to the next dividend payment.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK:L) paid a dividend of GBX 18.00 per ordinary share on 3 October 2013. The shares went ex-dividend on 7 August and the record date was two days later, on 9Â August. For the week commencing 5 August, the share price fluctuated as shown in

Table 11.1

.

TABLE 11.1

GlaxoSmithKline share price fluctuation

| Date | Price (GBX) | Price± (GBX) |

| Monday, 5 August 2013 | 1,705.00 | |

| Tuesday, 6 August 2013 | 1,694.00 | (11.00) |

| Wednesday, 7 August 2013 | 1,670.00 | (24.00) |

| Thursday, 8 August 2013 | 1,659.50 | (10.50) |

| Friday, 9 August 2013 | 1,663.00 | 3.50 |

Sources:

Yahoo! Finance (online) GSK:L share prices, available from

http://finance.yahoo.com

. [Accessed Wednesday, 9 October 2013]

Note that the share price dropped GBX 24.00 on the ex-dividend date; some of this drop can be explained by the removal of the dividend (GBX 18.00 per share) from the share price.

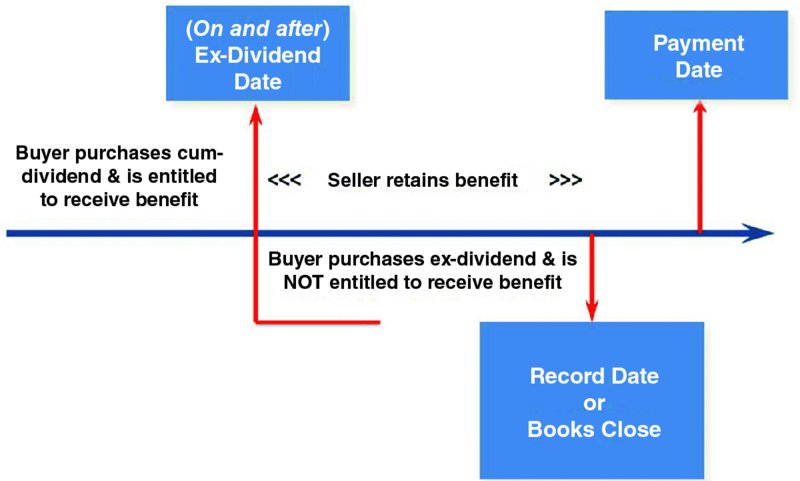

Figure 11.2

shows the timeline from the original announcement of the dividend through to the payment date.

FIGURE 11.2

Cum- and ex-dividend timeline

The third key date is the

payment date

. This can occur weeks, if not months, after the record date and is not governed by either the record date or the ex-dividend date. For example, Vodafone (VOD:L) paid its final dividend for 2013 on 7 August 2013, almost two months after the record date (14 June) and the ex-dividend date (12 June).

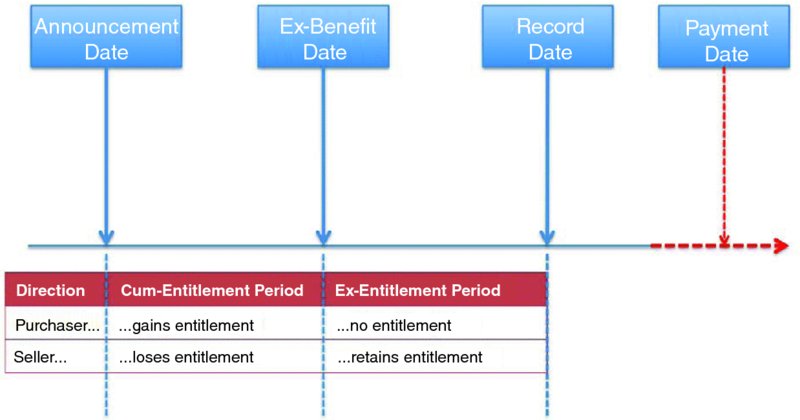

We now have three key dates to be concerned with, and each of these should be diarised and checks made to ensure that any investors holding the shares receive the correct amount of dividend and on the correct date. Furthermore, we can now identify two trading periods:

- Cum-entitlement period:

Where the investor executes a purchase trade and is entitled to receive the benefit (the dividend in this case) and the seller loses this entitlement. - Ex-entitlement period:

Where the investor executes a purchase trade and is not entitled to receive the benefit and the seller retains the benefit. This is shown in

Figure 11.3

.

FIGURE 11.3

Normal cum-benefit and normal ex-benefit trading

A situation can arise whereby an investor purchased shares cum-dividend but settlement was delayed (e.g. the seller did not have sufficient securities to enable the settlement to take place). In this situation, who do you think will receive the dividend? Remember, to receive a dividend, the investor's name must be on the shareholder register. In this case, it is the seller whose name is on the shareholder register and who will receive the dividend. However, as the purchase was traded cum-dividend, it should be the purchaser who is entitled to receive the dividend. There are two solutions to this problem:

- The purchaser (or the purchaser's agent) must claim the dividend from the seller, remembering that there might be more than one seller involved.

- The clearing house would be aware that, although the transaction was dealt cum-dividend, the purchaser's name was not on the shareholder register in time for the record date. The clearing house will automatically “compensate” the purchaser by debiting the seller's cash account and crediting the purchaser's cash account.

This compensation process is very much more efficient and timely compared with market claims; nevertheless, corporate action staff will need to monitor the situation carefully.

The situation with bonds is rather less complicated than with shares for the following reasons.

Firstly, coupon payment dates for fixed-income bonds are known in advance (i.e. from the date the bonds are issued) and can therefore be diarised. This also applies for bonds with variable coupon amounts, even though the actual coupon amount is not known until the coupon rate is fixed with reference to a specified benchmark interbank offered rate such as LIBOR, EURIBOR, etc.

Secondly, as the issuers of bearer bonds do not know who their bondholders are, the issuers have to rely on the bondholders to claim their coupons from the issuer's paying agent. Traditionally, this involved removing (known as

clipping

) the coupon from the host bond and presenting it to the issuer's paying agent. This coupon clipping had to be done some time in advance of the coupon payment date so that there was sufficient time for the coupon to be presented to the paying agent. Exactly how long was governed by the type of bond.

Thirdly, issuers of registered bonds would maintain a bondholder register similar to equities and could therefore make the coupon payment to whoever's name was on the register.