Footloose Scot (14 page)

Authors: Jim Glendinning

GROUP ADVENTURES

_______

1968

STUDENT TOUR TO MAO'S CHINA

In 1967 I resigned my job as executive director of Educational Travel Inc. in New York. I had worked for the agency for five years, had travelled a lot and learned much in the job. Now I was looking for something new, perhaps in Europe. First I planned a round-the-world trip while I worked out what. I took a train to Los Angeles, then a cruise ship to Tahiti from where I flew on to New Zealand. Continuing to Australia, I made contact with the Australian Student Union, sister organization of the people I worked for in the States.

The Student Union in Australia in those days farmed out its travel program to a small commercial agency, run by a jovial mustached former RAF Squadron Leader who had trained Battle of Britain pilots. I had previously met him at an International Student Travel Conference in Copenhagen. When I saw that his travel agency was about to run a student trip to China I asked if I could go as a paying customer, using my British passport. "No problem, sport." he said. So, in May 1968 I joined a group of 57 Australian students on a three week tour of mainland China, only a year after the Cultural Revolution had convulsed the country.

The group I joined contained a number of Chinese scholars looking to get an insight into what was happening in China. The majority were tourists like me, just wanting to get a glimpse of mysterious China. At that time there was little direct contact between the West and China. Australia had diplomatic relations with China since it supplied the regime with wheat but it was not until four years later, in 1972, that Nixon visited China and diplomatic relations were established.

In 1966 Chairman Mao launched The Great Cultural Revolution to regain the loyalty of the Chinese masses. He felt that liberal bourgeois tendencies had crept into society diluting the message of pure Communism. Across the country, millions were mobilized and called Red Guards. Their job was to root out suspect elements in Chinese society, teachers, bureaucrats or anyone who might be straying from the socialist path, and to make an example of them. A year and a half later when we arrived the Cultural Revolution had lost some of its initial energy, but was still very much alive, as we would find out.

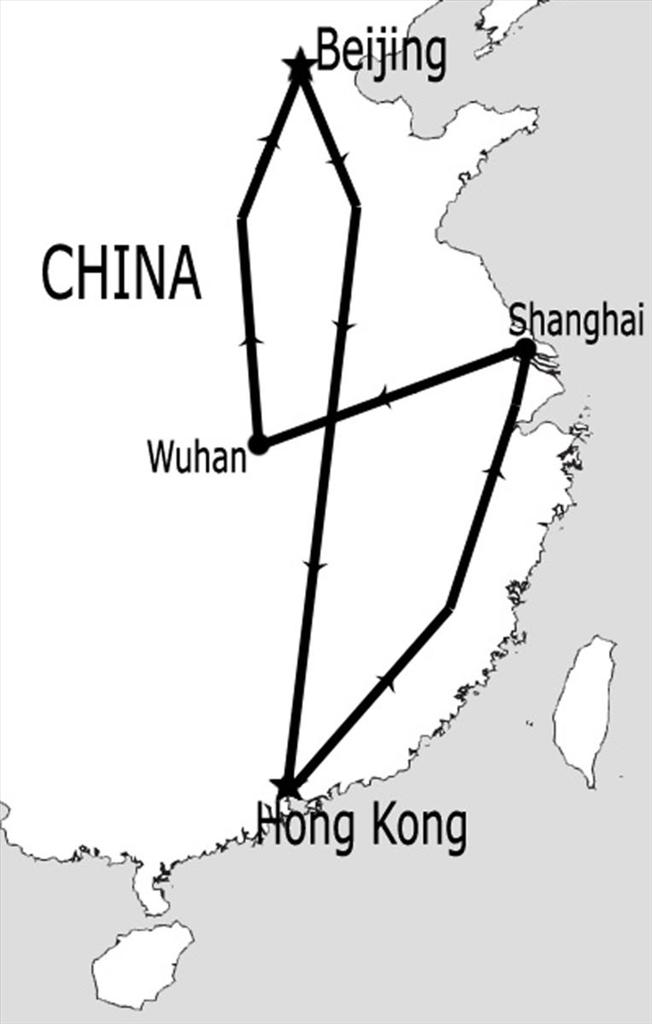

We followed a three week itinerary by plane, train and bus to Shanghai, Wuhan, Chinan and some smaller towns, and finally to Beijing before returning to Hong Kong, our starting point. We saw all the main tourist sights and enjoyed a lot of good food and plenty of beer. In Shanghai our guides made a point of telling how the sign outside the Foreigners Club on the Bund (Shanghai's waterfront drive) said: "Dogs and Chinese not permitted." We visited a model farm, a school, a factory and Mao's birthplace; later, in wild mountain terrain, we watched the Red Army practicing tank maneuvers. We connected briefly with the culture of ancient China in Old Peking and with its history when we stood on the Great Wall.

We were warned that our trip would be heavily chaperoned and tightly programmed, and we would be subject to constant political propaganda. At each place visited there would be a throng of people holding up poster-size Mao pictures, each person with a copy of the

Little Red Book,

a 312-page booklet with a red plastic cover known as

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse Tung.

Each member of our group was given a copy immediately we crossed the border from Hong Kong.

It was winter and, as we moved north, it became progressively colder. The population was all bundled up, and to our eyes looked the same. People were busy everywhere doing manual work. Our impression of living conditions was that everyone was taken care of, but there were not many comforts available, certainly no luxuries. We often stayed at old hotels which had been reopened to accommodate a group of our size. We saw all the tourist sights such as the Forbidden City in Beijing, China's best preserved imperial palace, in addition to places our hosts thought we should see.

Among the non-tourist sights we visited was a school where we saw 6-year olds chanting anti-USA slogans. In the classroom, where a copy of the Red Book was prominently displayed under the chalk board, a soldier of the People's Liberation Army stood in the background to make sure that the teaching was politically correct.

At one point during the tour we stayed at a commune and did some symbolic hoeing of the land. The earth was rock-hard, and the temperature was below freezing. It was without real purpose but still we went along with the idea without too much complaint because we understood the propaganda nature of the tour.

We were accompanied by many guides and minders and there was little chance to stray from the group. When we did have some free time and could stroll around on our own, the reaction of local Chinese people was often sheer astonishment; they gaped at us. Sometimes as we entered an institution for a formal visit, I would see Chinese teenagers in the background pointing and laughing at the foreigners with large noses. We were probably the first Westerners they had seen.

What sticks in the mind these many years later are not the Ming Tombs or the Great Wall but an incident which could have ended the trip. By the end of the first week, some in the group were beginning to chafe at the constant propaganda. We had had numerous receptions with formal speeches of welcome, cups of green tea, and expressions of mutual respect which took forever to translate. By now we had learned the words of "The East is Red," the national anthem of the Cultural Revolution, so we could sing along heartily with our hosts.

It was perhaps inevitable, given the independent frame of mind of the average Australian student, that an incident would occur. The incident happened following a flight to Shanghai, and it involved a student who was sitting next to me on the plane. In flight we had been given a snack and then the hostesses encouraged us to sing "The East is Red". I noticed that my seat mate was whiling away his time by adding a mustache to Mao's face which featured on the tag of his carry-on bag. I thought nothing of it.

We got off the plane at Shanghai and went into a room in the terminal building for a reception. After an hour of the usual formulaic speeches and responses, there was a sudden disturbance. A man in a worker's uniform, clearly agitated, entered from a side door and approached the chairman of the reception committee, waving a piece of paper in his hand. The committee chairman listened and looked at the piece of paper. It was the baggage tag, with Chairman Mao's added mustache, and it had got separated from the bag. The cleaning crew had found it.

In no time at all the tone of the meeting changed. The Chinese started speaking loudly among each other, some pointing in our direction, the speeches forgotten. The Australian tour leader looked grim as he spoke privately with the Reception Committee chairman. The interpreters did not say anything, and seemed as confused as the students in the group. After a while, the tour leader stood on a chair and shouted for everyone to be quiet, and that he had an announcement to make.

"We've got a major problem here, which only a radical solution will take care of," he said. He continued, saying that the Chinese said their country had been insulted and insisted on a public self confession. Otherwise the future of the tour was in doubt. "We are in their country," he continued, "and should live by their rules, however we might disagree." It was a difficult concept for some in the group to accept. The group started to argue, some saying the whole thing was totally overblown, that no insult was intended and the Chinese should get real. Others insisted we should apologize, do whatever was necessary to save the tour. This point of view prevailed. After some minutes of argument the student who had caused the problem stood up. Alarmed that his thoughtless action might jeopardize the tour, he said he would do a public self confession, on the spot. He just wanted to be told what to say.

And this is what finally happened. The student said his actions had been bourgeois, stupid and insulting to the Chinese hosts. He asked for forgiveness and hoped that the tour could continue. His apology went on for some time. But it was sufficient. The group may not have realized at the time, but

author and interpreter, beijing

we were witnesses at first hand, to a feature of the Cultural Revolution, this one without violence.

POLITICAL GRAFFITI ON MING TOMB

POSTER OF CHAIRMAN MAO

AUTHOR AND INTERPRETER, BEIJING

A year earlier, events like this were commonplace and often fatal, as millions of Red Guards ransacked cultural and religious sites; in Tibet Buddhist monks were forced at gunpoint to tear down their monasteries. Dissidents, many of them teachers, were forced to confess and paraded them through the streets with signs around their necks. They were spat on and beaten, and many killed. Today the Chinese authorities calculate that during the Cultural Revolution 30 million died, many from starvation as whole populations were displaced.

What we had seen was something as valuable in its own way as the tourist sights such as as The Great Wall or the Winter Palace. We had seen at first hand an alien political system at work. The group soon regained its spirit, drank more beer than before, but was careful not to provoke any incidents which might require a public self confession.

The group returned to Hong Kong at the end of the tour and attended a press conference where our first-hand views of mysterious China were eagerly awaited. For me, I was glad to have gone. It was a learning experience for the whole group, and many were clearly shocked to have been a witness to such an uncommon occurrence, the public self-confession.

In the back of my copy of the

Little Red Book,

I wrote that the revisionists had failed and that the Party was in control again. Little did I know that within eight years, Mao would have died and that a new China would arise, still confined within the Communist political straightjacket but free to practice economic capitalism, the success of which we are having to come to terms with today.