Footloose Scot (11 page)

Authors: Jim Glendinning

At another point a group of British Army soldiers, on a mountain training exercise, were having a tea break. They explained that there was an agreement whereby units of the British Army regularly came to Kenya for jungle and mountain exercises. I got into a futile discussion about the British Army's action in the infamous Bloody Sunday shootings in Northern Ireland in 1988.

Leaving the soldiers, I plodded on and came to the least pleasant part of the climb. This was a stretch of boggy moorland, with huge tussocks of grass sticking up from a muddy bottom. You could try jumping between the grassy knolls, or simply plod through the squishy mud going round the knolls. Neither way was pleasant.

By late afternoon I arrived at Shipston's Camp (13,897 feet), the hut where everyone spends the night before summiting Point Lenana, the third peak of Mt. Kenya. This was about 700 feet lower than the higher peaks Mt. Batian (17,057 feet) and Mt. Nelion but they were ice-covered and required climbing equipment. In the hut was a couple from Australia, and we arranged with a guide who lived at the hut to take us to the summit the next morning.

We left at 4 a.m. the next morning, under a near-full moon, intending to reach the summit by daybreak. It was extraordinarily and surprisingly cold; I had assumed since we were close to the equator, the temperature would be warmer. Not so. We plodded up an easy glacier, trying to find a balance between going quicker so our bodies warmed up yet not so fast that our lungs complained. At the col below the summit there was a small hut; the Australian man, suffering from the altitude, decided to stay there while the guide, his girlfriend and I continued.

Forty minutes later we stood on the top of Point Lenana (16,355 feet) as the sun started to come up. We were the only summiters. Forgetting the cold, we watched as the darkness faded, revealing first the colors of the nearby mountain rocks, then the glacier and further below the forest vegetation which I had trudged through the previous day. Soon the whole panorama of mountain, forest and valley came into sight and the glorious spectacle of Africa was on display. We took some photos, drank some tea and went back down to the hut to pick up our fourth member.

Kenya has a well-developed railroad network, one of the positive results of British colonial rule. Each evening at 7 p.m. a smartly painted train pulled by a steam engine left Nairobi for Mombasa, a thirteen hour trip. The two-berth sleeping compartments had clean sheets on the bed, and the restaurant car served a silver service dinner. In the morning there was time to view the changing landscape as the train passed through Tavo National Park before reaching the coast.

On a train ride in Tanzania, I had a less happy experience. This was on the train from Dar es Salaam to Arusha, the jumping off place for Serengeti National Park, the Ngorongoro Crater and for Mt. Kilimanjaro. This train had four-berth compartments, and I had a top berth. We had opened the window since there was no ventilation or air-conditioning. I was just dropping off to sleep when I felt something move tentatively across my face. I woke up to see a thin black arm withdrawing from the window on the outside. Someone on the roof of the train had reached down and put his hand through the open window, hoping to find a wallet or watch perhaps hidden under a pillow. This time, it didn't work.

Nairobi has most things any tourist could want: fine hotels, a variety of good restaurants, safari outfitters and good shops. Most people speak English. Thorn Tree Cafe at The New Stanley Hotel is a popular eating place for well-heeled tourists who can discuss their safari while checking for any messages or plans on the notice board of the Jacaranda Tree which grows there. There's another side to Nairobi which tourists don't often see, young men working scams as well as simple pickpockets.

I needed to change some money on the black market. I have done these transactions a number of times at various places around the world and had, I thought, become quite savvy. There's a basic problem here in that one is breaking the law, and the other factor is that one is dealing with unsavory if not outright crooked types, typically young men with flashy clothing.

I was stopped on a Nairobi street by a young man, who said quietly, "Want to change some money?" I nodded yes, so he drew me to one side. I told him I wanted to change $50, and we agreed on a rate. He said that we couldn't change the money on the street, it was too risky. I should come with him to an office of his friend, right close by. This sounded wise and sensible.

We went in to what seemed like a travel agency, and a man came down some stairs. He asked me for my $50 and said he would go upstairs and get Kenyan shillings from his safe. There seemed no other exit from the shop, so I handed over the money. Three minutes later, both men came running down the stairs, saying the police were coming, and thrust an envelope in my hand as they ran past me, saying, "Here is your money, now go!" I stepped out of the office. The men had disappeared down the street. I opened the envelope and found it stuffed with pieces of newspaper.

I also needed a cheap flight to London, then I could relax and enjoy Nairobi. Here I was more successful. In the train from Mombasa to Nairobi I met a shirtless, sweaty New Zealander with oil on his hands. He explained that he was a driver for an overland tour group, and the engine of his truck, right now at a campsite near Mombasa, needed a spare part. He had called his base in London, and they advised him the part would be sent care of an office address in Nairobi. He had just received a message that the part had arrived, and was on his way to pick it up.

He sounded like a man tuned into budget travelers' requirements. I asked him how I could get back to London cheaply. "No problem, mate," he said, "Go to the Hotel Iqbal on Latema Road, and go into the building next door to the left. Go up to the second floor, then turn right and follow the corridor all the way until it stops. On your left is Room 220, go in there and ask for Sammy. He'll fix you up."

I followed his instructions, found Room 220, knocked and went in. A man with a round, smiling face, sitting at a desk with a small Sudan Airways flag on it, immediately said, "You want a ticket to London?" He was Sammy, the Sudan Airways representative, and I had found the right place for a cut-price ticket. Unfortunately, although the price was half the price of British Airways, the flights did not run every day. Sammy recommended me to Aeroflot who flew daily. So I flew Aeroflot via Aden and Moscow to London at about the same fare Sudan Airways was offering via Khartoum.

RWANDA

I arrived in Rwanda after a difficult trip through western Tanzania. Kenya had been easy to visit; good infrastructure, tourist-friendly, and English-speaking: Tanzania less so. The economy was in bad shape and the political situation worse. I had taken a ferry down Lake Victoria to the Tanzanian town of Mwanza. I was used to taking local buses and now there were none, only occasional trucks. You paid for a ride if you could get a truck to stop.

The problem was that there was very little traffic. The long distance trucks carrying goods from Kenya to Rwanda demanded a high price to carry a passenger, particularly a white tourist. There were Missionary and NGO Land Cruisers, but none stopped. I spent two nights in a village called Lusahanga in western Tanzania, waiting for a truck. About 30 other people were also waiting—just outside of town on the highway. I found a room in a guest house and the young fellow running it became friendly. After he finished work I kicked around an old football with him. He knew I was waiting for a ride and said he would help.

On the third day in the afternoon he told me there was a truck leaving shortly from the village, and the driver, with whom he had agreed a low price, would take me. I paid the driver and climbed into the back, which already had perhaps 15 people sitting on the top of sacks. This way, after five hours, we arrived at the Tanzania/Rwanda border. It was now getting dark. I got my passport stamped and walked out of Tanzania. Since there was little likelihood of getting a ride at night, and I didn't even know if the Rwanda border post was open, I put up my tent in the strip of land between the two countries. Apart from the floodlights and occasional vehicle noise, I felt quite safe, since there were soldiers on duty on both sides of the border. Just in case, I had a can of Mace, a flashlight and an open knife stuck in the ground next to my sleeping bag, ready to repel boarders. Nothing happened during the night and I slept without interruption for eight hours.

The next morning I walked two hundred yards to the Rwanda border post, and got stamped in. There were some trucks waiting for clearance, and I negotiated a good price for a ride to Kigali, the capital, three hours away. Kigali was a prosperous looking place. There were one or two modern hotels with French names, and some well stocked stores. The size of Switzerland and with a standard of living far ahead of neighboring Burundi, it has one of the densest populations in Africa, 10 million people living in 17,000 square miles of extremely fertile land. The tragedy which would kill 800,000 people was still seven years off but I neither read nor heard anything to suggest that such a cataclysmic event was in the offing.

In Kigali I tried to get permission to camp in the grounds of a Presbyterian Church, which the guidebook had suggested was possible. Not this time, or not for this tourist. So, late at night, I slept rough in the parking lot of a football stadium, behind some bushes and out of the glare of the security lamps. The next morning, taking a bus into the city center, I noticed the well dressed young secretaries on the bus keeping well clear of the dirty looking white tourist with a large backpack. I found my way to the bus station, and waited for a minibus to fill up which would take me to the Parc des Volcans in the north of the country.

I arrived early evening in the Parc des Volcans, the very first national park in Africa, founded in 1925. It lies in the mountainous northwest of the country close to the borders with Congo and Uganda. The habitat is rain forest with a lot of bamboo growth and it is the home of the mountain gorilla. Thirty-two permits are issued daily to tourists, mainly to tour groups.

Fortunately, a young Englishman, a solo traveler like me, turned up and I got talking with him. On his way through Zaire to Rwanda he met some Belgians who used to run the Parc des Volcans. From them he got a note asking the current park administration to include him in the first gorilla sighting group. He got me included in this request and we booked on the next day's gorilla sighting trip.

We assembled at 9 a.m. the next morning. We were fifteen tourists with two park rangers to guide us. First the rangers gave us a briefing. We had been told that we could observe the gorilla family for 40 minutes, at a distance of twenty feet, and we must obey our guides completely. If the silver back daddy gorilla expressed hostility by grunting or agitation, we were to remain seated with eyes downcast. We were to follow the instructions of our guides precisely both for our own safety and to keep interference with the gorillas to a minimum. We drove for about 50 minutes in a truck, then set off on foot on a track through rainforest.

The guides had a pretty good idea where the family would be since they had observed them the day before. The family of six gorillas which we hoped to observe moved slowly and left a wide trail of flattened vegetation. Sure enough, after about an hour of slow going through the wet undergrowth, the rangers signaled for us to stop. They told us the family was just ahead of us, taking a rest in a clearing in the undergrowth. The rangers went back to the front of our group and made grunting noises to the gorillas to let them know we were friendly. We moved forward as quietly as conditions permitted, then sat down with some jostling among the tourists to see who could be in the front, closest to the gorillas. I was at the back but was not concerned since my camera was not going to work in the subdued light.

In a forest clearing, with shafts of sunlight filtering through the trees, the gorilla family was taking a break. The head of the family, a large silver back of perhaps 300 pounds, reclined against a tree trunk chewing on a bamboo stalk. From time to time he looked around at his family of youngsters who were swinging through the trees enjoying some play time. The mother was foraging nearby in a dense thicket for tasty morsels. The smallest gorilla was scratching itself and the elder ones were chasing each other, jumping from branch to branch, then onto the ground where they rolled over and over. They could be a family of humans having a picnic, I thought.

What is so moving about these animals? They are so big, yet so gentle. They look human; their movements are familiar to us as humans. By nature they are non-aggressive. They have a sort of majesty in their appearance and movements. The main attraction, the silver back, can weigh up to 400 pounds and measure 5'9" when upright. Their life span measures 30 to 50 years.

Our cameras clicked and clicked. Someone was taking notes, no one talked. There was no movement among the gorillas except from the youngsters. The mother had come back with some shoots to chew on, and was also sitting down. This gorilla family was used to encounters with humans. After about 40 minutes, the silver back heaved himself upright and trudged off into the undergrowth. The rest followed. Our 40 minutes was up and the principal actor had exited the stage.

SOLO TRAVELER

_______

1990

CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA

MEXICO

Mexico is larger than most of us think; at 758,249 square miles it is nearly three times the size of Texas with a population approaching 114 million. The distance from Tijuana to Cancun is 2,795 road miles. The Mexican bus system, the largest in the world, is excellent. From local buses, which are often rattletrap former school buses with bald tires imported from the USA, to luxury coaches with three reclining armchairs abreast, buses cover the length and breadth of Mexico, operating round the clock.

Until 2000 there was still a Mexican national passenger railroad system. So, in 1990 I boarded a long distance express train from Nuevo Laredo to Mexico City, the first leg of a trip which would take me as far as Puerta Natales in southern Chile. Paul Theroux's travel memoir, The Old Patagonian Express (1979), describes a trip where he travels through Central and South America using trains wherever possible. My trip was in the same direction, but I was planning also to hike, take a bus or to fly wherever I could get free tickets.

The train for Mexico City left Nuevo Laredo on time. It was sparsely filled, and I sat with some other Americans in a car with reclining seats. After departure food, which was included in the ticket price, was brought to our seats. The casual, breezy chat which often arises on such journeys among temporary acquaintances was marred by one beefy older man in a bright shirt. He was ex military, he let everyone know, and he had been to Mexico many times. He then started to make jokes about Mexico and Mexicans in a loud voice, oblivious to Mexican passengers or the train staff who might understand English. No one paid much attention to him, but this didn't put him off. Instead of challenging him, or telling him to shut up, which I might have done, I got into conversation with a young map maker from Austin, Texas before it got dark, and the Ugly American stopped talking and we all fell asleep.

In a public park in Mexico City I caught sight of a popular Mexican acrobatic display performed by a group called

"Voladores"

(Flying Acrobats). Four Indians in costumes were hanging head down, attached by a rope to their feet which connected to a platform at the top of a 50 foot pole around which they spun in a slow circle. Another Indian sat at the top of the pole, beating a drum. All had peeled off the platform and were now dropping slowly as the rope unwound and the pole spun around until they reached the ground and could stand upright. Drama, color and music, it was very Mexican. I didn't know what to make of it except that it was a wonderful surprise and it was free.

I continued the next day by train to Oaxaca, this time in a private sleeping compartment. On arrival I sat in the

zocalo,

the central plaza, munching on a snack of chicken mole as I watched tourists emerge from hotels and get into tour buses. Oaxaca, which I was to visit several times over the next few years, is a wonderful destination. A college town, located at 5,058 feet, and capital of the state of the same name, it offers the visitor imposing Baroque churches and shady plazas, a large central market and hotels to suit every budget. It is a dynamic place with a strong cultural tradition and a large artifacts industry and only six miles distant from the important pre-Columbian archeological site, Monte Alban.

From Oaxaca I started on a series of daily bus trips, heading always south. At the end of a six to eight hour day in one or more buses, I would look for a cheap hotel near the bus station. My experiences were fleeting. In Guatemala the countryside was rich with color, the capital drab. El Salvador, the next country, was tense. A civil war had been sputtering for the last nine years, still unsolved.

At the bus station in Managua, Nicaragua there was a commotion just before my bus was about to leave. Some women passengers complained that the driver was drunk. There was a delay. Two bus company officials turned up with a policeman who led the driver away. This was a long-distance bus with through service to San Jose, capital of Costa Rica. A young American woman said the bus was delayed until the following morning. She invited me and a student from England who was also waiting for the San Jose bus to come and stay at her house for the night. We accepted.

Her story deserved attention. She had left her comfortable home in Seattle, motivated by a desire to help the women in Nicaragua. She had been working in Managua at a women's health clinic for eight months, had learned enough Spanish to get by, and dressed in the local manner. Politically she was to the left, a supporter of Daniel Ortega and the ruling Sandinistas, opposed to the CIA-backed Contras. She was the sort of American volunteer in Nicaragua whom the Miami paper labeled Sandalistas, sympathizers of the regime. The paper was making a joke based on sandals, the footwear of many. I admired her conviction and courage giving up middle class comforts for the uncertainty and discomfort of helping people in a foreign country. She was a throw-back to the Sixties when volunteerism was a novel and attractive concept to America's youth.

The next day, at the same hour, a bus was ready with a sober driver. We arrived without incident in San Jose, the capital of Costa Rica. Here life was totally different. A confident, affluent place, Costa Rica was held as a model for Central America. Instead of guerilla war, in Costa Rica there was not even an army. The popular President, Oscar Arias Sanchez, had won a Nobel Peace Prize. Twenty-five percent of the country had been put aside as national parks. The streets were filled with traffic and the sidewalks with happy people. Outside a hamburger joint was a huge papier mache burger, five foot high. The volunteer stared in wonder.

After a couple of days visiting museums, taking a trip to the coast, and enjoying some of the comforts of San Jose, I was ready for the last country in Central America. This was the year of the US invasion to topple Noriega in Panama and I was not relishing the possibility of more tension. As I waited for a local bus to the town of David in northern Panama, a beefy American in civilian clothes standing in front of me pointed to a straggling column of soldiers barely visible in the distance heading for the mountains. "There go the yellow bellies" he snorted derisively, referring to Noriega's troops. Who was he? CIA?

From David, I continued along the Pan American highway. Changing buses again in Santiago, I took a local bus to a small village 30 miles east. I then got off and, following instructions given to me earlier, walked half a mile south on the main road, then turned right under an ornamental gateway onto a private drive. This lead to an attractive hacienda, called

finca

in Panama. I rang the door bell. A grey haired, petite lady opened the door and said: "You're right on time, Jim, come on in". It was Margot Fonteyn.

I had met Margot Fonteyn a few months earlier in Houston at the house of a mutual friend. Now 71, she was still a picture of elegance and grace. She had been in Houston for cancer treatment. When she found out about my trip, she insisted I come and stay at her home in the country near Panama City. She was so charming and easy to talk to that I had no trouble in accepting, although I warned her I might be a little travel worn. And here I was.

She had been very precise in asking when I could arrive. So I had worked out that it would take me eight days using local buses; I was right on schedule. I soon got cleaned up and enjoyed the comfort of the spacious ranch house, which looked towards the Pacific Ocean. Her sister from England was visiting and we sat around under shade trees chatting. The contrast between days on the move in crowded buses, nights in cheap hotels and food bought from vendors at bus stations, and being welcomed to a comfortable home, discussing books with sophisticated people while sipping cool drinks was total.

The next day we took a walk along the beach, and had a picnic. Margot was limping due to cancer radiation treatments so her man-servant, Ventura, gave her a hand over rough ground. Ventura had previously tended her husband, Roberto Arias, a politician and diplomat, who had been crippled by a bullet and bedridden for many years until his death the year before.

The reason Margot wanted to know exactly when I would arrive is that she intended to put on a party. When she was married, she and her husband regularly held parties at the

finca

and invited politicians, diplomats and people from the arts world in Panama City. Now Margot wanted to host a party with me as the surprise guest.

So I cleaned myself up even more, and was introduced to a variety of people from Panama City, the UK ambassador, a bookshop owner, some models and one or two politicians, old friends of her husband. None of whom had met a backpacker before. A model tried on my backpack, which got a lot of laughs. They wanted to know where I was going. When I said by foot through the Darién Gap, they were worried. To them no one ventured south of the capital, Panama City. To venture deep into Darién Province and then continue by foot through the jungle into Colombia was in their opinion madness. I told them I had a map and that I had done this sort of solo trek before and, if there were problems, I would turn back. They still looked doubtful.

After four days of feeding and resting, I was ready to move on. Margot was seriously concerned about my safety so I promised her I would call her from Colombia once I arrived. I had had a wonderful rest and had got to know a remarkable woman as much as four days permitted. I was not to know I wouldn't see her again. She died from cancer later in 1990 in a Panama hospital.

Ventura drove me to the bus station in Panama City where I caught a minibus going south to Meteti. After four hours the minibus arrived and with a few other minibus passengers I caught a truck going to the next town, Yaviza, the last town of any significance before the Colombian border. The truck bogged down in mud. I got out to help push, as did everyone else, and fell flat on my face. It didn't really matter. I was going to an area where bathing and cleanliness were not important. In Yaviza I found a basic hotel with a good lock on the door, but no window. The most important part was the lock; and it was also clean. I wandered around muddy streets and was surprised to see a US Army patrol boarding a boat and leaving downstream. I'd forgotten all about the invasion since talking with the CIA man in David, six days earlier.

I was now deep inside Darién Province, and from now on transportation would be by river. This area of southern Panama measures 3,000 square miles of mountainous rain forest and river valleys. It is home to the Darién National Park which lies to the east. The route I was following is called the Darién Gap since it is the 54-mile missing part in the Pan American Highway which runs from Prudhoe Bay in Alaska to the bottom of South America, about 29,800 miles. The region is home to the indigenous Cuna and Choco Indians, whom I would meet soon.

I found a motor boat heading upstream the next morning after my night in a room with no window. Now my adventure was really beginning. I hadn't seen and didn't expect to see any other backpackers this year. Normally each dry season several dozen hikers would go south into Colombia. There was even a guidebook about the area (Darién Gap by Bradt Travel Guides), which I carried with me. But this was the year of the US invasion and most hikers seemed to have changed their plans.

After four hours the motor boat reached Boca de Cupa, a collection of huts on the riverbank. By now, as the river narrowed, the motor boat could go no further. I then negotiated a price for a seat in a dug out boat owned by an old Indian who took me to the next village, Pucoro, where I asked the tribe elder for permission to stay. We were talking simple Spanish, but I could just as easily have mimed my request. I spent the night in a Meeting Room. I felt comfortable with the Indians, simple and shy people. I bought a small woven piece of cloth, and kept my camera shut.

LOS VOLADORES

, MEXICO CITY

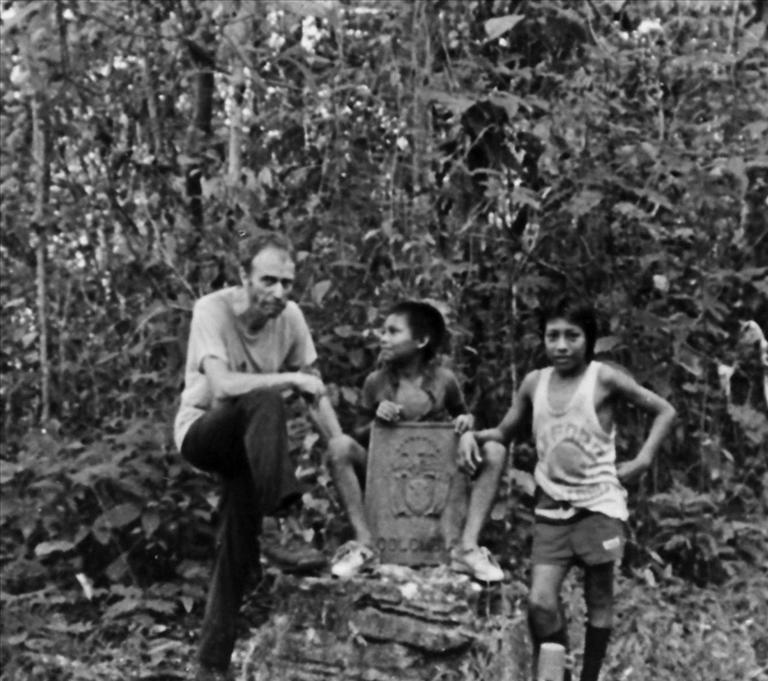

PALO DE LAS LETRAS

, PANAMA