Footloose Scot (15 page)

Authors: Jim Glendinning

GROUP ADVENTURES

_______

1974

DRIVING TO INDIA

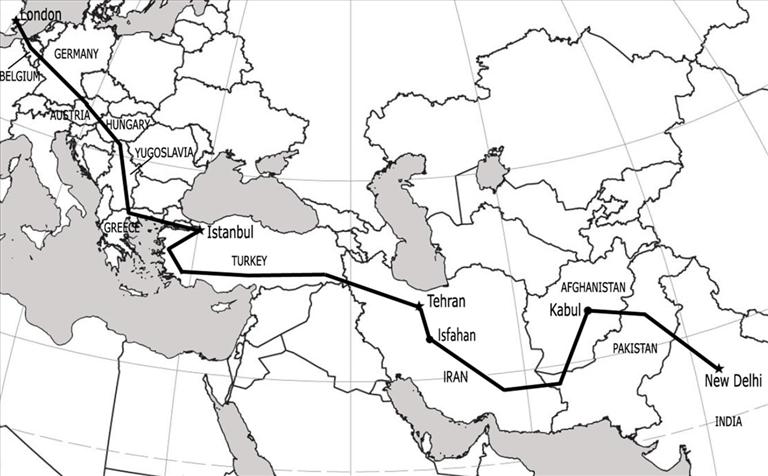

I got married in 1973 and with my wife Christine, who had a similar travel bug, decided on an overland trip to Asia. We bought a Bedford camper van, and planned a six-month trip to India. We would then continue to Southeast Asia and Japan by plane or ship before coming back to New Delhi, where we had parked our camper, and drive home.

A travel agency in London, Trailfinders, offered advice to potential overlanders. Overlanding meant driving your own vehicle from London to Goa or Kathmandu or through Africa. Pre-planning, they said, would save us expense, breakdowns, accidents, headaches and perhaps even jail. Make no mistake, they added, without pre-planning we would be well advised to stay at home and enjoy a safe, middle-class holiday in Bognor Regis (a town on the English Channel). They should know; they were specialists in this field.

They provided a loose leaf Pre Departure Handbook with 61 separate route segments from London to New Delhi together with maps. It also contained a mass of information ranging from country-to-country visa requirements, the best type of vehicle, how to obtain a vehicle carnet (the vehicle permit for temporary entry into a foreign country), as well as insurance, inoculations recommended for each country and food suggestions.

We had a useful interview in London with the Trailfinders staff person, Harvey Bonham, who wrote the pre-departure handbook. We didn't tell him we had already bought a Bedford Camper, not one of their recommended vehicles. It had a softer suspension than VW or Ford vans, but in the event we were not let down. Also, I took a trainee mechanics course for a couple of days at a garage in Oxford. We put a roof rack on the camper and strapped on fuel cans and an extra tire. Excited and a little nervous, we were ready to go. In the mid-1970's morale in England as well as the economy was rock bottom. It was a good time to be leaving. Twelve countries and 10,000 miles to New Delhi lay ahead.

In March 1974 we took the cross Channel ferry to Belgium then linked up with the German autobahn network, heading south. Buying local food and cooking in the van, using campsites or sometimes just parking overnight by the side of the road, we drove through Germany and Austria then over the Loibl Pass into Yugoslavia, the same route I had hitch-hiked in 1958. We detoured to the Dalmatian Coast and camped on quiet beaches.

Old Dubrovnik's claim to be "The Pearl of the Adriatic" was well deserved. A walled city founded in the 7

th

century as a Byzantium fortress, stuck between the blue Adriatic Sea and the coastal mountain range. it was crammed with wonderful old buildings and featured pedestrian streets paved with marble. We then turned inland and headed southeast across wild mountain terrain. I saw Cyrillic lettering on shop signs, and noticed roadside memorials to partisans killed fighting the Germans during World War II. Nine days after leaving England we arrived in Istanbul.

Truly a world city, Istanbul enjoys a stunning location on a strategic waterway with a foot on two continents. It has been capital city of three empires as its many mosques, palaces and monuments bear witness. Western and tourist friendly on one hand, its other side suggests a Middle Eastern lifestyle.

Istanbul was no place to drive around so we parked the Bedford safely and explored the city by foot, on trams and by ferry. Memories such as watching two men walk by hand in hand across Galata Bridge, smelling roasting meats and getting lost in the Grand Bazaar linger with the grander sights of Topkapi Palace, the Sultan Ahmed Mosque (the Blue Mosque) and immense Museum of Hagia Sophia. This mighty structure surmounted by a massive dome and held up by enormous buttresses has since its dedication in 360 AD served as a cathedral to both Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic religions, as a mosque for 500 years and finally, when it was secularised in 1935, as a museum. We avoided carpet salesman and various rogues on the sidewalks, and after two busy days were ready to take the ferry across the Bosporus into Asia.

We detoured to the battlefields and cemeteries of the Gallipoli peninsula, alternatively moving and numbing in its profusion of graves, trenches, obelisks and memorials. This failed campaign in 1915, proposed by Winston Churchill, was intended to secure the Dardanelles waterway and capture Constantinople. Instead, the Turkish victory laid the ground work for Ataturk's new Turkey. After landings by French, British, Australian and New Zealand troops, the attack stalled after many casualties leading to a withdrawal from the peninsula. You won't escape a showing of Peter Weir's

Gallipoli

movie if you stay in any of the budget hostels; and the site remains a magnet for young Australians.

Along Turkey's Mediterranean coast we enjoyed warming weather and empty seaside campsites. Inland we explored the rock dwellings of the ancient Christian settlements of Goreme, and the white calcium-formed plateau with terrace formations in Pamukkale, the thermal baths and the nearby Roman remains at Hierapolis. The further east the wilder the scenery became; it was now spring and wildflowers added some color to increasingly barren landscape.

Driving through a cold rain shower in mountain terrain, we found the road blocked by a herd of emaciated sheep tended by a bedraggled old shepherd holding his coat over his head. He looked at our vehicle and at us and, nodding towards two sickly looking sheep at the back of the herd; he drew his hand across his throat. He was not threatening us; he was suggesting we give his two sheep a ride in our vehicle or they would die. Born on a sheep farm, I couldn't refuse. We loaded the shepherd and his smelly sheep into the back of the van, and drove them to a lower altitude. The odor of wet wool remained with us for days.

We had experienced good roads so far, well surfaced and maintained. The Bedford was running well, and we had started to personalize the vehicle calling it Bedford. "Would Bedford be happy with this detour?" was the sort of question we might ask when looking at a choice of routes. Often in the mountains or along the coast we would pull over for a picnic lunch, heating tea on the stove. At night we would look for a campsite but, if none was available, simply find a secluded spot and deploy the pop-up roof. I always checked for a clear escape route, and had Bedford pointing in the right direction in case of a hurried departure, but we never had any unwelcome nighttime visitors.

On the main highways, the principal source of anxiety were the long-distance trucks, sixteen- or eighteen-wheelers, driving fast and often in the center of the road, covered in dust and bearing a TIR sign (International Road Transport). They were hauling manufactured goods .to Asia and produce to Europe. Many of them originated in Tehran.

Eastern Turkey was wild, primitive and not welcoming. Bands of wild dogs ran through the empty streets of bleak towns, and kids would sometimes throw rocks at the vehicle. Sometimes we took shelter in a local hotel, rather than risking camping. A little hostility was something anticipated, and we had no thought of turning back; there was always the anticipation of the next country.

Driving into Iran things changed completely, and for the better. Smart guards in US-style uniforms manned the border crossing, and there was a working water fountain in the immigration office. We were warmly greeted and quickly processed. A line of trucks waiting to get into Iran stretched half a mile was not so fortunate. We didn't know it, but we arrived during the last days of the Shah's rule.

Tehran was large, modern and bustling, not normally a place we would look forward to.. But fortunately an Iranian friend from my Oxford days called Reza was expecting us. We stayed at his apartment and he acted as a tour guide for two days. It was a relief not having to do all the planning ourselves as well as being constantly alert; now we had a friend to show us around the city, to see the opulent Golestan Palace (The Palace of Flowers) and the treasures of the National Museum as well as to restaurants which we would never have found on our own. One evening we met up with a friend of his, a slight, sensitive-looking man. Towards the end of a night of beer drinking he confided he had just resigned from Savak, the Shah's secret police. He could not stomach the methods of torture inflicted on political suspects and we didn't ask for details. One wondered about his own future, as someone who had renounced the agency.

From Tehran we drove south to Isfahan in seven hours, expectantly. A Persian proverb says: "Isfahan is half the World", and we soon found out why. Mosques, minarets, palaces and caravanserais filled the town, as well as bath-houses and bazaars. The graceful curves and intricate blue tiling of the mosaic domed mosques dominated the skyline. Tree-lined boulevards led to Nagshsh-a Jahan Square, the largest in Iran, surrounded by wide galleries. The city of over one million was one of the few spared by the Mongols, hence the rich treasures visible today. An outstanding example of a wide range of Islamic architectural styles from the 11

th

century, it was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. We drove around, and then walked around for a long morning in something of a daze at the richness of the architectural feast before turning to mundane matters like finding a campground.

From Isfahan a good road led us south for 300 miles to Shiraz. Known as the "City of roses and nightingales", Shiraz can't match Isfahan's architectural wonders. But it is a centre of arts and letters, and home of Iran's two greatest poets from the 13

th

and 14

th

centuries, Saadi and Hafez. This pleasant oasis was a good rest stop before we turned east on what the map described as "a desert or dangerous road" to the city of Kerman. We were so far south that, instead of turning round and heading back to Tehran, we decided to take a southern route eastwards through Iran into Baluchistan Province of Pakistan and from there enter Afghanistan.

The desert road was unpaved, hard-packed sand and gravel. Occasionally there were soft patches where Bedford got stuck. I was alarmed and momentarily panicked as the rear wheels sank deeper into the sand the more I pressed on the accelerator. There were very few other vehicles from whom to ask for help, and I didn't relish a night stranded in the open desert. We had no sand ladders, so I started throwing an overcoat and winter sweaters under the back wheels while Christine gunned the engine. This did the trick and we started to move again, with some shredded garments as souvenirs.

Finally after a fourteen- hour day we arrived in Kerman, a large provincial capital located at 5,700 feet, and found a hotel with secure parking. The next stage to the Pakistan border was going to be equally tricky. The map showed a long stretch of highway marked "open desert road". Now there was no defined road, simply a set of tire tracks 100 yards across. This was the open desert road, which ran through flat and featureless terrain. We drove on as it got dark, wishing to reach a small town called Darzin and soon found that night driving involved a certain procedure. The technique was to drive with high beams then, when sighting an oncoming vehicle, to switch off our own lights for 30 seconds, and then switch on again when the approaching vehicle extinguished its lights. The road bed was sufficiently wide, and the surface smooth, that this method of passing at night was not as scary as it first sounded.

The next day we came to the abandoned city of Bam. Founded 2,000 years ago, Bam once had a population of 11,000 but was abandoned in 1722 after an Afghan invasion. Built from mud and bricks and dominated by a citadel, it lay silent in the baking sun, totally lifeless. It was weird to be the only people there and a little unsettling. It was no place to linger.

Later the road surface turned hard and stony, with washboard ridges. A vehicle with a harder suspension might have coped by travelling at 30 to 35 miles per hour and skating over the washboard. Our speed dropped to about twelve miles per hour as we lurched from one trough to the next, with all the contents of the camper shaking and making an irritating cacophony while great clouds of dust were thrown up by the wheels. The heat was severe, and Bedford had no air-conditioning.

On top of the problem of the road condition, the direction took us into a border area with local tensions. The few villages we passed were surrounded by high walls with slits for guns, so we kept on driving. "Is this really worth it?" asked Christine as we got out of the vehicle and stretched in the full blast of mid-day heat. She had been an uncomplaining trooper for the whole trip until now but now was being constantly bounced around, short of drinking water, covered in dust and very hot. I at least had the steering wheel to hang on to and the road to concentrate on. The trouble was we were so far along this route, that backtracking at this point would mean going all the way back to Tehran, an extra 800 miles of driving.

“BEDFORD”