Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (45 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

12.85Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Family Nurse Partnership programme to be extended [Available online] https://www.gov.uk/ government/news/family-nurse-partnership-programme-to-be-extended

Family Nurse Partnership [Available online] http://education.gov.uk/commissioning-toolkit/Content/PDF/Family%20Nurse%20Partnership%20FNP.pdf

Eligibility for the Family Nurse Partnership programme: Testing new criteria. [Available online]http://www.iscfsi.bbk.ac.uk/projects/files/Eligibility-for-the-Family-Nurse-Partnership-programme-Testing-new-criteria.pdfListen to the broadcast by Miranda Sawyer (2012) The Teenage Pregnancy Myth. Available: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01dhhpq.

Older mothers

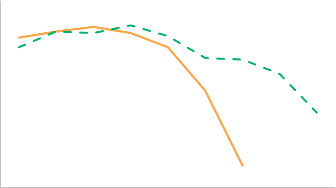

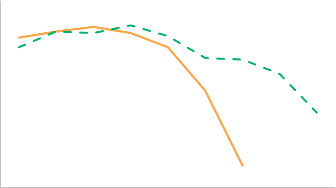

At the other end of the fertility spectrum are older mothers. Women’s fertility probably ends around 10 years before the menopause, or sometime in their mid-forties (Velde and Pearson 2002; American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2012). The optimum age for women to bear children is between 20 and 35 years of age, according to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG 2011); this partly reflects the steep decline in women’s ability to produce offspring, observed after age 35 (Menken et al. 1986; see Figure 5.15). Whilst the use of assisted reproductive technologies has extended the age at which many women are able to conceive, there are still health concerns attendant with conception and pregnancy at advanced maternal age (see Table 5.4, for definitions). Some key concerns regarding health of women of advanced maternal age and their babies are shown in Figure 5.16. Historically, the phenomenon of older mothers was associated with women of lower socioeconomic status and higher parity, but more recently there has been a shift so that older mothers are more commonly women of higher socioeconomic status and lower parity (Velde and Pearson 2002; Chan and Lao 2008; Carolan et al. 2011).1.210.80.60.40.20

15−19 20−24 25−29 30−34 35−39 40−44 45−49 50−54 55−59

15−19 20−24 25−29 30−34 35−39 40−44 45−49 50−54 55−59

107

107

Relative fertility rate wife

Relative fertility rate wife

Relative fertility rate husband

Relative fertility rate husband

Figure 5.15

Graph showing the variation in relative fertility rate for wives and husbands, who are not using contraceptive measures, with age where the wives were born between the years 1840– 1859 (data taken from Menken et al. 1986).

Table 5.4

Advanced maternal age: definitions

Classification terminology

Definition (age in years)

Authors

Advanced maternal age Delayed childbearing≥35≥35Delbaere et al. (2007)SOGC Genetics Committee (2012)High maternal age≥40Delbaere et al. (2007)Advanced maternal age≥35 modified to ≥40 to better reflect a cut-off in terms of identifying high-risk pregnancies in contemporary maternity careChan and Lao (2008)Very advanced maternal age Mature gravidaExtremely elderly gravida≥44 or ≥45 at deliveryreflecting the use of assisted reproductive technologies to achieve older age conceptionsCallaway et al. (2005); SOGC Genetics Committee (2012)Heffner (2004; Table 5.5) reports the relative risks of conception of babies who have chromo- somal abnormalities being born to women, according to maternal age. However, these figures may be negated, in individual women, by the use of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis and or donor gametes.A predominantly biophysical approach to older parenthood tends to focus on the idea that later conception is both more difficult to achieve and attendant with poorer outcomes. This does not always reflect other confounding factors, such as the differing health statuses of a population of women who are considered older. Demonstrable benefits of older motherhood include a significant reduction in childhood unintentional injuries and hospital admissions for children by the age of three and a significant decline in hospital admissions for children up to

Risk of chronic hypertensionRisk of pre- gestational and gestational diabetes

Risk of chronic hypertensionRisk of pre- gestational and gestational diabetes

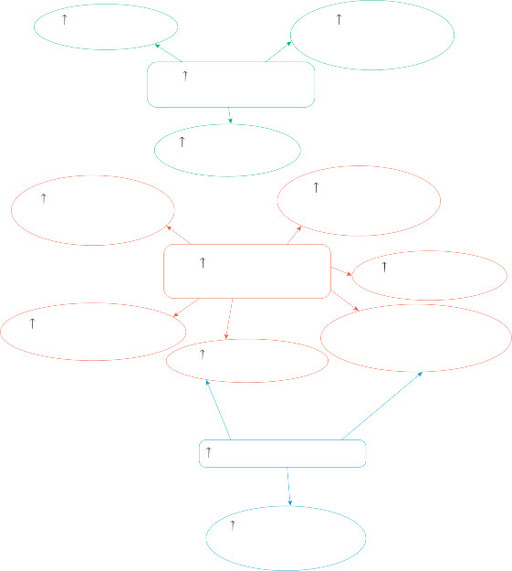

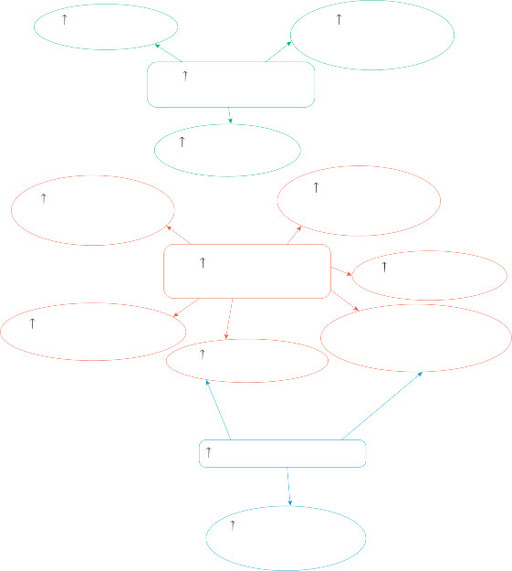

108Risk of maternalco-morbidities and mortalityRisks of maternal mortalityRisk of caesarean section (elective andemergency)Risk of multiple pregnancy (natural & ART)Risk of obstetric complicationsRisk gestational diabetes (3 to 4 fold)10 fold risk of placenta praevia (low absolute risk)Risk of pre-term birth4 to 8 fold risk of ectopic pregnancy compared with younger womenRisk to the embryo or fetusRisk of babies born with congenital abnormalities

108Risk of maternalco-morbidities and mortalityRisks of maternal mortalityRisk of caesarean section (elective andemergency)Risk of multiple pregnancy (natural & ART)Risk of obstetric complicationsRisk gestational diabetes (3 to 4 fold)10 fold risk of placenta praevia (low absolute risk)Risk of pre-term birth4 to 8 fold risk of ectopic pregnancy compared with younger womenRisk to the embryo or fetusRisk of babies born with congenital abnormalities

Figure 5.16

Risks attendant with older age conception (Didly et al. 1996; Callaway et al. 2005; Chan and Lao 2008; Mbuga Gitau et al. 2009; CMACE 2011; SOGC Genetics Committee 2012).

Table 5.5

Relative risk of babies with chromosomal abnormalities according to maternal age (Heffner, 2004)

Maternal age at birth (years)

Maternal age at birth (years)

Risk of Down’s syndrome

Risk of any chromosomal abnormality

201/16671/526251/12001/476301/9521/385351/3781/192401/1061/66451/301/21109the same age (Sutcliffe et al. 2012). Midwives, obstetricians, practice nurses and General Practi- tioners (GPs) need to be aware of the influence of societal trends, personal and cultural factors, on the timing of parenthood. Partly due to the liberty afforded by availability of safe and effec- tive contraceptive methods and also the provision of effective assisted reproductive technology, women are able to delay childbearing for a number of reasons (Velde and Pearson 2002). They may wish to pursue higher education, achieve career goals, become financially stable, obtain secure marriages, or intimate partnerships. Women may also wish to start second or subsequent families with new partners (Shaw and Giles 2009; Society of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) Genetics Committee 2012; Dabrowski 2013). Midwives should, therefore, be prepared to offer compassionate and sensitive support for older mothers. As with teenage mothers, care should not be based on assumptions, but rather evidence-based; it should respect the dignity of the woman and her family using effective communication to develop a positive partnership (NICE 2010; Commissioning Board Chief Nursing Officer and DH Chief Nursing Adviser 2012).

Disability and parenting

New mothers across the childbearing age spectrum may also have pre-existing disabilities. Aperson with a disability:

. . . has a physical or mental impairment... which has. . . a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities . . .

(Equality Act 2010, p. 3)More broadly speaking disability is ‘

an umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions

’ (WHO 2013). The White Paper, ‘Valuing People’ (DH 2001), found that parents with disabilities; including learning disabilities (intellectual and social disabilities affecting people’s ability to learn and cope independently) received patchy and underdevel- oped support. Walsh-Gallagher et al. (2013) found that disabled pregnant women were often impeded from experiencing a positive pregnancy. Disabled mothers may face stigma and prejudice from society, including health professionals: they may be perceived as being totally dependent on others, and therefore incapable of effective parenting. Disabled mothers may face assumptions about their suitability for parenthood, and distaste at the evidence of their being sexually active; they may also face heightened scrutiny due to concerns over their110parenting adequacy (Malacrida 2007; MacDonald 2009; Rosqvist and Lövgren 2013; Walsh- Gallagher et al. 2013). Some of these objections may not be dissimilar to those faced by ado- lescent or older mothers. One of the key policy objectives from ‘Valuing People Now’ (DH 2009,

Older mothers

At the other end of the fertility spectrum are older mothers. Women’s fertility probably ends around 10 years before the menopause, or sometime in their mid-forties (Velde and Pearson 2002; American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2012). The optimum age for women to bear children is between 20 and 35 years of age, according to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG 2011); this partly reflects the steep decline in women’s ability to produce offspring, observed after age 35 (Menken et al. 1986; see Figure 5.15). Whilst the use of assisted reproductive technologies has extended the age at which many women are able to conceive, there are still health concerns attendant with conception and pregnancy at advanced maternal age (see Table 5.4, for definitions). Some key concerns regarding health of women of advanced maternal age and their babies are shown in Figure 5.16. Historically, the phenomenon of older mothers was associated with women of lower socioeconomic status and higher parity, but more recently there has been a shift so that older mothers are more commonly women of higher socioeconomic status and lower parity (Velde and Pearson 2002; Chan and Lao 2008; Carolan et al. 2011).1.210.80.60.40.20

15−19 20−24 25−29 30−34 35−39 40−44 45−49 50−54 55−59

15−19 20−24 25−29 30−34 35−39 40−44 45−49 50−54 55−59 107

107 Relative fertility rate wife

Relative fertility rate wife Relative fertility rate husband

Relative fertility rate husbandFigure 5.15

Graph showing the variation in relative fertility rate for wives and husbands, who are not using contraceptive measures, with age where the wives were born between the years 1840– 1859 (data taken from Menken et al. 1986).

Table 5.4

Advanced maternal age: definitions

Classification terminology

Definition (age in years)

Authors

Advanced maternal age Delayed childbearing≥35≥35Delbaere et al. (2007)SOGC Genetics Committee (2012)High maternal age≥40Delbaere et al. (2007)Advanced maternal age≥35 modified to ≥40 to better reflect a cut-off in terms of identifying high-risk pregnancies in contemporary maternity careChan and Lao (2008)Very advanced maternal age Mature gravidaExtremely elderly gravida≥44 or ≥45 at deliveryreflecting the use of assisted reproductive technologies to achieve older age conceptionsCallaway et al. (2005); SOGC Genetics Committee (2012)Heffner (2004; Table 5.5) reports the relative risks of conception of babies who have chromo- somal abnormalities being born to women, according to maternal age. However, these figures may be negated, in individual women, by the use of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis and or donor gametes.A predominantly biophysical approach to older parenthood tends to focus on the idea that later conception is both more difficult to achieve and attendant with poorer outcomes. This does not always reflect other confounding factors, such as the differing health statuses of a population of women who are considered older. Demonstrable benefits of older motherhood include a significant reduction in childhood unintentional injuries and hospital admissions for children by the age of three and a significant decline in hospital admissions for children up to

Risk of chronic hypertensionRisk of pre- gestational and gestational diabetes

Risk of chronic hypertensionRisk of pre- gestational and gestational diabetes 108Risk of maternalco-morbidities and mortalityRisks of maternal mortalityRisk of caesarean section (elective andemergency)Risk of multiple pregnancy (natural & ART)Risk of obstetric complicationsRisk gestational diabetes (3 to 4 fold)10 fold risk of placenta praevia (low absolute risk)Risk of pre-term birth4 to 8 fold risk of ectopic pregnancy compared with younger womenRisk to the embryo or fetusRisk of babies born with congenital abnormalities

108Risk of maternalco-morbidities and mortalityRisks of maternal mortalityRisk of caesarean section (elective andemergency)Risk of multiple pregnancy (natural & ART)Risk of obstetric complicationsRisk gestational diabetes (3 to 4 fold)10 fold risk of placenta praevia (low absolute risk)Risk of pre-term birth4 to 8 fold risk of ectopic pregnancy compared with younger womenRisk to the embryo or fetusRisk of babies born with congenital abnormalitiesFigure 5.16

Risks attendant with older age conception (Didly et al. 1996; Callaway et al. 2005; Chan and Lao 2008; Mbuga Gitau et al. 2009; CMACE 2011; SOGC Genetics Committee 2012).

Table 5.5

Relative risk of babies with chromosomal abnormalities according to maternal age (Heffner, 2004)

Maternal age at birth (years)

Maternal age at birth (years)Risk of Down’s syndrome

Risk of any chromosomal abnormality

201/16671/526251/12001/476301/9521/385351/3781/192401/1061/66451/301/21109the same age (Sutcliffe et al. 2012). Midwives, obstetricians, practice nurses and General Practi- tioners (GPs) need to be aware of the influence of societal trends, personal and cultural factors, on the timing of parenthood. Partly due to the liberty afforded by availability of safe and effec- tive contraceptive methods and also the provision of effective assisted reproductive technology, women are able to delay childbearing for a number of reasons (Velde and Pearson 2002). They may wish to pursue higher education, achieve career goals, become financially stable, obtain secure marriages, or intimate partnerships. Women may also wish to start second or subsequent families with new partners (Shaw and Giles 2009; Society of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) Genetics Committee 2012; Dabrowski 2013). Midwives should, therefore, be prepared to offer compassionate and sensitive support for older mothers. As with teenage mothers, care should not be based on assumptions, but rather evidence-based; it should respect the dignity of the woman and her family using effective communication to develop a positive partnership (NICE 2010; Commissioning Board Chief Nursing Officer and DH Chief Nursing Adviser 2012).

Disability and parenting

New mothers across the childbearing age spectrum may also have pre-existing disabilities. Aperson with a disability:

. . . has a physical or mental impairment... which has. . . a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities . . .

(Equality Act 2010, p. 3)More broadly speaking disability is ‘

an umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions

’ (WHO 2013). The White Paper, ‘Valuing People’ (DH 2001), found that parents with disabilities; including learning disabilities (intellectual and social disabilities affecting people’s ability to learn and cope independently) received patchy and underdevel- oped support. Walsh-Gallagher et al. (2013) found that disabled pregnant women were often impeded from experiencing a positive pregnancy. Disabled mothers may face stigma and prejudice from society, including health professionals: they may be perceived as being totally dependent on others, and therefore incapable of effective parenting. Disabled mothers may face assumptions about their suitability for parenthood, and distaste at the evidence of their being sexually active; they may also face heightened scrutiny due to concerns over their110parenting adequacy (Malacrida 2007; MacDonald 2009; Rosqvist and Lövgren 2013; Walsh- Gallagher et al. 2013). Some of these objections may not be dissimilar to those faced by ado- lescent or older mothers. One of the key policy objectives from ‘Valuing People Now’ (DH 2009,

Other books

Good as Gone by Amy Gentry

The Granite Key (Arkana Mysteries) by N. S. Wikarski

Five O’Clock Shadow by Susan Slater

BLUE MERCY by ILLONA HAUS

Questing (Cosmis Connections, Book One) by Huffert, Barbara

A Matter of Magic by Patricia Wrede

Seneca Rebel (The Seneca Society Book 1) by Rayya Deeb

Summer Surrender (Phases Series, Book Six) by Green, Bronwyn

We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families by Philip Gourevitch