Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (44 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

12.64Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

35-39

40 and over

40 and over

Year

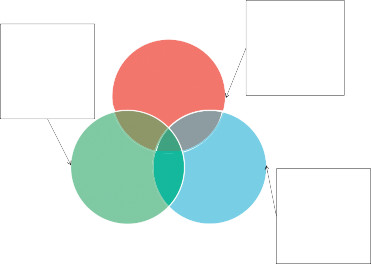

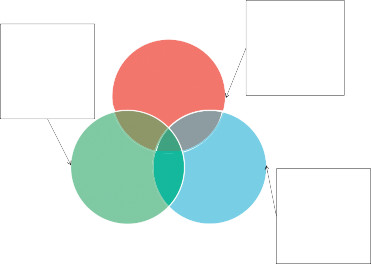

Figure 5.13

Annual conception rates (conceptions per 1000 women in age group (ONS 2013d).Menarche usually occurs between 9 to 12 years of age (Tiran 2008; Thain 2009; Blackburn 2013) and is indicated by the onset of menstruation in the adolescent girl. The cessation of female fertility is marked by the menopause or the climacteric which is the gradual process by which a woman transitions from a reproductive to a non-fertile state. The climacteric describes the changes that occur from the perimenopausal, through the menopausal, to postmenopausal stages (Blackburn 2013). From around 37.5 years of age, women experience accelerated atresia (degeneration) of ovarian follicles; ovaries become less responsive. Menopause can occur anytime from the middle thirties to the mid-fifties (median age is 51). Natural menopause is diagnosed retrospectively, after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea (Martin 2010). However, the upper age limits for pregnancy may be increased, by the use of assisted reproductive tech- nologies and other health and lifestyle interventions.

Adolescent parents

Adolescent parenthood seems to concern health professionals and policy makers which can be deduced from policy drives such as the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (Social Exclusion Unit 1999) which aimed to halve the rate of conception in under-18s and establish a clear downward trend in under-16 conceptions. The terms ‘teenager’ and ‘adolescent’ are often used synonymously, but need definition. Martin (2010) gives a clinical definition of adolescence as the developmen- tal stage that occurs from the time of puberty to adulthood, between 12 to 19 years old in girls, and 14 to 19 years old in boys. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2004, p. 5) defines ado- lescent pregnancy as, ‘pregnancy in a woman aged 10–19 years’. The Office for Nationals Statis- tics (ONS 2013a) discusses teenage conception in terms of, ‘under-18 conceptions.’ Figures are sometimes cited as pregnancies among 15–17 year olds. In 2011 the under-18 conception rate continued to decline; reaching its lowest level since 1969 at 30.9 conceptions per 1000 women aged 15–17. In 2010 the conception rates among the under 20s were the only ones which decreased as a whole compared to the remainder of age groups of childbearing women, and in 2011, conception rates declined in all women under 25 (ONS 2013b). The Abortion Statistics, England and Wales (DH/ONS, 2013) suggest that has been a decline in teenage abortion rates (under 16 and under 18), in recent years. The Teenage Pregnancy Independent Advisory Group (2010) reported that between 1998 and 2008, there was a decline of 13.3 % in teenage concep- tions overall, although some areas that had been more consistent in applying the ‘Teenage Pregnancy Strategy’ had achieved declines of up to 45%.Young parenthood raises the spectre of early sexual activity, linked with moral objections and sometimes concerns regarding safeguarding of children. Young adolescent girls may have been subject to non-consensual sexual intercourse (rape) or coercive sexual intercourse which resulted in pregnancy, via partners of similar ages or significantly older (Barter et al. 2009). Young fathers are also more likely than older fathers and other young men to have been sub- jected to violence or sexual abuse (Barter et al. 2009). Midwives and other health professionals must use their professional judgement to decide whether it is right to maintain confidentiality for adolescent girls who have conceived under the age of 16, or whether there is cause to inter- vene because abuse is suspected, where significant risks to the welfare of children outweigh their right to privacy (Department for Schools, Children and Families and DH 2009). In such instances locally agreed safeguarding protocols must be observed and implemented.Teenage pregnancy indicates unprotected sexual intercourse, which is a risky behaviour, in the context of transient and/or multiple partnerships. Statistics for the occurrence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) support this. The report ‘HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infec- tions in the United Kingdom’ (The UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2006) found that young people were overrepresented in the statistics for the incidence of genital

103

103

Table 5.2

Teenage pregnancies: health outcomes for women and babies

Teenage/adolescent study group

Teenage/adolescent study group

Comparison group

Health concerns among the study group (teenage mothers)

Authors

Mothers aged 11–19Mothers aged (20–29)Greater neonatal and infant mortalityGilbert et al. (2004)Increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes among teenage pregnancies, despite a lower caesarean section rateMothers aged 13–19 yearsMothers aged 20–34 yearsIncreased risk of congenital anomalies of central nervous system, gastrointestinal and muskoskeletal/integumentary systems in babiesChen et al. (2007)Teenage mothers who smokedAdult mothers who smokedBabies born to teenage mothers who smoked were significantly more likely to be born at a low birth weightDewan et al. (2003)104Smoking Substance misuse (including alcohol) Unprotected sex/ early age for first sex relationship/ multiple partnersSocial and cultural factors

Family background Social support structures Opportunities (employment/ education)Area of residenceRisk behavioursHealth statusDiet and nutrition Anatomical development Mental health statusAccess to health services

Family background Social support structures Opportunities (employment/ education)Area of residenceRisk behavioursHealth statusDiet and nutrition Anatomical development Mental health statusAccess to health services

Figure 5.14

Context of teenage pregnancy.Chlamydia infections, gonorrhoea and genital warts. The highest rates of genital warts appeared among the 16–19 years age-group in women and in the 20–24 years age group in men: diag- noses of these and other STIs (such as Herpes simplex) have risen in frequency in recent years (Public Health England 2013). These diseases are potentially deleterious to the short and long- term health of mothers, babies and their exposed sexual partners. Teenage pregnancy has been linked to a number of poor outcomes for the health of women and babies (see Table 5.2). However, growing evidence suggests that the problems are more attributable to complex social factors than merely young maternal age. The relationship between the context of teenage pregnancy (see Figure 5.14) and its outcomes needs to be considered by midwives and the interprofessional team. Risk factors significantly associated with conception by 16 years and for

Table 5.3

Risk for teenage pregnancy (Sloggett and Joshi 1998; McCulloch 2001; WHO 2004; Allen et al. 2007; Smith 2010)

Category of risk factor

Category of risk factor

Specific risks for teenage pregnancy

Social circumstancesAspirationsBeliefsBehavioursmisuse and smoking. Five out of nine drug dependant mothers who committed suicide in thelatest Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (2006–2008) were teenagers (CMACE 2011).Experiences

40 and over

40 and overYear

Figure 5.13

Annual conception rates (conceptions per 1000 women in age group (ONS 2013d).Menarche usually occurs between 9 to 12 years of age (Tiran 2008; Thain 2009; Blackburn 2013) and is indicated by the onset of menstruation in the adolescent girl. The cessation of female fertility is marked by the menopause or the climacteric which is the gradual process by which a woman transitions from a reproductive to a non-fertile state. The climacteric describes the changes that occur from the perimenopausal, through the menopausal, to postmenopausal stages (Blackburn 2013). From around 37.5 years of age, women experience accelerated atresia (degeneration) of ovarian follicles; ovaries become less responsive. Menopause can occur anytime from the middle thirties to the mid-fifties (median age is 51). Natural menopause is diagnosed retrospectively, after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea (Martin 2010). However, the upper age limits for pregnancy may be increased, by the use of assisted reproductive tech- nologies and other health and lifestyle interventions.

Adolescent parents

Adolescent parenthood seems to concern health professionals and policy makers which can be deduced from policy drives such as the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (Social Exclusion Unit 1999) which aimed to halve the rate of conception in under-18s and establish a clear downward trend in under-16 conceptions. The terms ‘teenager’ and ‘adolescent’ are often used synonymously, but need definition. Martin (2010) gives a clinical definition of adolescence as the developmen- tal stage that occurs from the time of puberty to adulthood, between 12 to 19 years old in girls, and 14 to 19 years old in boys. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2004, p. 5) defines ado- lescent pregnancy as, ‘pregnancy in a woman aged 10–19 years’. The Office for Nationals Statis- tics (ONS 2013a) discusses teenage conception in terms of, ‘under-18 conceptions.’ Figures are sometimes cited as pregnancies among 15–17 year olds. In 2011 the under-18 conception rate continued to decline; reaching its lowest level since 1969 at 30.9 conceptions per 1000 women aged 15–17. In 2010 the conception rates among the under 20s were the only ones which decreased as a whole compared to the remainder of age groups of childbearing women, and in 2011, conception rates declined in all women under 25 (ONS 2013b). The Abortion Statistics, England and Wales (DH/ONS, 2013) suggest that has been a decline in teenage abortion rates (under 16 and under 18), in recent years. The Teenage Pregnancy Independent Advisory Group (2010) reported that between 1998 and 2008, there was a decline of 13.3 % in teenage concep- tions overall, although some areas that had been more consistent in applying the ‘Teenage Pregnancy Strategy’ had achieved declines of up to 45%.Young parenthood raises the spectre of early sexual activity, linked with moral objections and sometimes concerns regarding safeguarding of children. Young adolescent girls may have been subject to non-consensual sexual intercourse (rape) or coercive sexual intercourse which resulted in pregnancy, via partners of similar ages or significantly older (Barter et al. 2009). Young fathers are also more likely than older fathers and other young men to have been sub- jected to violence or sexual abuse (Barter et al. 2009). Midwives and other health professionals must use their professional judgement to decide whether it is right to maintain confidentiality for adolescent girls who have conceived under the age of 16, or whether there is cause to inter- vene because abuse is suspected, where significant risks to the welfare of children outweigh their right to privacy (Department for Schools, Children and Families and DH 2009). In such instances locally agreed safeguarding protocols must be observed and implemented.Teenage pregnancy indicates unprotected sexual intercourse, which is a risky behaviour, in the context of transient and/or multiple partnerships. Statistics for the occurrence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) support this. The report ‘HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infec- tions in the United Kingdom’ (The UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2006) found that young people were overrepresented in the statistics for the incidence of genital

103

103Table 5.2

Teenage pregnancies: health outcomes for women and babies

Teenage/adolescent study group

Teenage/adolescent study groupComparison group

Health concerns among the study group (teenage mothers)

Authors

Mothers aged 11–19Mothers aged (20–29)Greater neonatal and infant mortalityGilbert et al. (2004)Increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes among teenage pregnancies, despite a lower caesarean section rateMothers aged 13–19 yearsMothers aged 20–34 yearsIncreased risk of congenital anomalies of central nervous system, gastrointestinal and muskoskeletal/integumentary systems in babiesChen et al. (2007)Teenage mothers who smokedAdult mothers who smokedBabies born to teenage mothers who smoked were significantly more likely to be born at a low birth weightDewan et al. (2003)104Smoking Substance misuse (including alcohol) Unprotected sex/ early age for first sex relationship/ multiple partnersSocial and cultural factors

Family background Social support structures Opportunities (employment/ education)Area of residenceRisk behavioursHealth statusDiet and nutrition Anatomical development Mental health statusAccess to health services

Family background Social support structures Opportunities (employment/ education)Area of residenceRisk behavioursHealth statusDiet and nutrition Anatomical development Mental health statusAccess to health servicesFigure 5.14

Context of teenage pregnancy.Chlamydia infections, gonorrhoea and genital warts. The highest rates of genital warts appeared among the 16–19 years age-group in women and in the 20–24 years age group in men: diag- noses of these and other STIs (such as Herpes simplex) have risen in frequency in recent years (Public Health England 2013). These diseases are potentially deleterious to the short and long- term health of mothers, babies and their exposed sexual partners. Teenage pregnancy has been linked to a number of poor outcomes for the health of women and babies (see Table 5.2). However, growing evidence suggests that the problems are more attributable to complex social factors than merely young maternal age. The relationship between the context of teenage pregnancy (see Figure 5.14) and its outcomes needs to be considered by midwives and the interprofessional team. Risk factors significantly associated with conception by 16 years and for

Table 5.3

Risk for teenage pregnancy (Sloggett and Joshi 1998; McCulloch 2001; WHO 2004; Allen et al. 2007; Smith 2010)

Category of risk factor

Category of risk factorSpecific risks for teenage pregnancy

Social circumstancesAspirationsBeliefsBehavioursmisuse and smoking. Five out of nine drug dependant mothers who committed suicide in thelatest Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (2006–2008) were teenagers (CMACE 2011).Experiences

Living in non-privately owned housing

Living in an economically inactive household

Social deprivation

No expectation of being in further/or higher education (by age 20 years)

Belief that >50% of peers are sexually active

Being drunk at least once a month at age 13

Pregnant teenagers are also more likely to engage in other ‘risk behaviours’ such as substance

Prior experience of physical and sexual abuse105teenage pregnancy, generally, are listed in Table 5.3. This suggests socioeconomic and personal factors may be more significant than age alone in influencing the short and long-term outcomes for adolescent parents and their children. Macvarish (2010) argues that concerns about young pregnancy are possibly symptomatic of hypocritical moralising in a society which largely approves of and promotes premarital sex, but disapproves of its visible consequences. These concerns tend to negate the idea of young mothers being rational, moral agents who choose motherhood (Macvarish 2010).Ethnic group may influence the prevalence and acceptability of teenage pregnancy. For example, in Europe there are significantly higher rates of teenage pregnancy in England than comparable European Union (EU) states (Aspinall and Hashem 2010). The Millennium Cohort Study showed wide variations of percentages of mothers from different ethnic groups in England who were teenagers at the birth of their first baby. The study showed that 34% of Bangladeshi mothers, 25% of Black Caribbean mothers, 18% of Pakistani mothers, 17% of white mothers, 13% of Black African mothers and 6.1% of Indian mothers gave birth for the first time as teenagers (Jayaweera et al. 2007). Multiple factors could influence these variations, including cultural approval or encouragement of early marriage and childbearing (Higginbottom et al. 2006) and the relative importance attached to further and higher education of young women. Adolescent pregnancy must be considered in its socioeconomic and cultural contexts to inter- pret its significance.Midwives must consider that adolescent pregnancy may be planned and desirable for mothers and families; they must also seek to understand, explore and address potential chal- lenges for young mothers and their babies. Family Nurse Partnerships (FNPs) exist to provide an intensive programme of nurse home-visiting services and support from early pregnancy through the first two years of the child’s life, for young pregnant mothers and fathers (with consent from mothers) (Department for Education n.d.; Birkbeck University 2012).Family nurses work alongside existing health and social services such as midwives and social workers, to support young parents. Further means of support include Doulas, such as the Goodwin Volunteer Doula Project in Hull, East Yorkshire which supports women with complex

106social factors throughout the childbearing period (Sandall et al. 2011). Positive collaboration between midwives, family nurses and Doulas can produce a supportive network and plan of care to meet the needs of teenage mothers. Teenage parenthood may present opportunities for positive life transformation and may therefore be seen as a positive life choice by the mother (Sawyer 2012). An example of good practice is a scheme called ‘the Schoolgirl Mum’s Unit’ in Kingston-Upon-Hull, which aims to provide education, opportunity, and support for young mothers and their babies to gain independence and increase future options (The Boulevard Centre n.d.); this project received an outstanding commendation for:

106social factors throughout the childbearing period (Sandall et al. 2011). Positive collaboration between midwives, family nurses and Doulas can produce a supportive network and plan of care to meet the needs of teenage mothers. Teenage parenthood may present opportunities for positive life transformation and may therefore be seen as a positive life choice by the mother (Sawyer 2012). An example of good practice is a scheme called ‘the Schoolgirl Mum’s Unit’ in Kingston-Upon-Hull, which aims to provide education, opportunity, and support for young mothers and their babies to gain independence and increase future options (The Boulevard Centre n.d.); this project received an outstanding commendation for:

‘ . . . promoting the achievement of girls and young women and in developing their future economic well-being . . . ’

(Ofsted 2009)Appropriate support, education and opportunities may reap rewards in helping young parents to be successful in parenting and making future, positive life choices and changes.

Further reading activityRead the following items to learn more about the role and purpose of the Family NursePartnership:

Further reading activityRead the following items to learn more about the role and purpose of the Family NursePartnership:

106social factors throughout the childbearing period (Sandall et al. 2011). Positive collaboration between midwives, family nurses and Doulas can produce a supportive network and plan of care to meet the needs of teenage mothers. Teenage parenthood may present opportunities for positive life transformation and may therefore be seen as a positive life choice by the mother (Sawyer 2012). An example of good practice is a scheme called ‘the Schoolgirl Mum’s Unit’ in Kingston-Upon-Hull, which aims to provide education, opportunity, and support for young mothers and their babies to gain independence and increase future options (The Boulevard Centre n.d.); this project received an outstanding commendation for:

106social factors throughout the childbearing period (Sandall et al. 2011). Positive collaboration between midwives, family nurses and Doulas can produce a supportive network and plan of care to meet the needs of teenage mothers. Teenage parenthood may present opportunities for positive life transformation and may therefore be seen as a positive life choice by the mother (Sawyer 2012). An example of good practice is a scheme called ‘the Schoolgirl Mum’s Unit’ in Kingston-Upon-Hull, which aims to provide education, opportunity, and support for young mothers and their babies to gain independence and increase future options (The Boulevard Centre n.d.); this project received an outstanding commendation for:‘ . . . promoting the achievement of girls and young women and in developing their future economic well-being . . . ’

(Ofsted 2009)Appropriate support, education and opportunities may reap rewards in helping young parents to be successful in parenting and making future, positive life choices and changes.

Further reading activityRead the following items to learn more about the role and purpose of the Family NursePartnership:

Further reading activityRead the following items to learn more about the role and purpose of the Family NursePartnership:Other books

Keeping the Promises by Gajjar, Dhruv

Sword by Amy Bai

Coping by J Bennett

The Pearl at the Gate by Anya Delvay

Lover Uncloaked (Stealth Guardians #1) by Tina Folsom

From The Ashes (After The Burn Series) by Colt, Shyla

The Wood Queen by Karen Mahoney

The Red Trailer Mystery by Julie Campbell

Wife or Death by Ellery Queen