Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (41 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

13.81Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

A commonly held belief within the culture that couples would only marry when they achieved the ability to set up, financially viable households, independently of their parents.

A comparatively late age of marriage; 25–26 for women and 27–28 for men (in early 1700sEngland).

Strong societal censure of extramarital sexual intercourse, with resultant stigma and penalties which reduced fertility outside marriage.The industrial revolution led to a relaxation of certain social restrictions on sexual relation- ships, due to the changing pattern of work and residency of adults (fewer household servants or tied workers): this was accompanied by a population explosion, and high levels of illegitimacy

(Bottero 2011). However, arguably, the nuclear family was already an established‘norm’ in North

(Bottero 2011). However, arguably, the nuclear family was already an established‘norm’ in North

93

West Europe.This portrayal of the traditional nuclear family is tempered with a broader vision of family life that represents the diversity of social arrangements in 21st century Britain. Longstanding vari- ations exist from the notion of nuclear family, for example, the ‘

extended family

’ defined by Bradley and Mendels (1978, p. 381) is ‘

. . . when a household is composed of one person and some other kin in addition to spouse or child.

’ Although the extended family model may be assumed to be more prevalent among certain ethnic groups, in the UK, they exist throughout society. Socioeconomic factors, such as national recession may create more extended family households and somewhat heighten their importance (Byrne et al. 2011). Extended family members, such as the baby’s grandparents, aunts and uncles may prove supportive and influential to parents. Family structures are also shaped by the marital status of the parents. The Office for National Statistics (ONS 2013a) report from the General Lifestyle Survey (GLS) for Great Britain (GB) showed that 49% of women aged over 16 were married; 21% of these women were single, 11% were cohabiting, and 10% were divorced or separated (Table 5.1). ONS (2013b) reported a declining trend in the proportion of first marriages for both partners between 1966 and 2011. A total of 82% of religious marriages were between partners who had never married before in 2011 compared with 60% of civil marriages. However, 88% of couples who married in civil cer- emonies and 78% of those who had religious ceremonies had cohabited prior to marriage (ONS 2013b). When parents remarry, it is considered that ‘

. . . stepchildren and joint biological children who live together . . . belong to a “blended” family

’ (Ginther and Pollak 2004, p. 4). In 2012, about 48% of live births were registered to parents who were either cohabiting, living separately, or who were single parents (ONS 2013c). Therefore midwives can expect to care for married, cohabiting and single mothers, within the varying family contexts. Occasionally, the baby may also be cared for by a single father.

Table 5.1

Marital status of women aged 16 or over in England and Wales 2011 (ONS 2013a)

Percentage of the population of women aged 16 or over

Married49Civil partnership0Cohabiting11Single21Widowed9Divorced7Separated2A more focused discussion of how the meaning of parenthood has evolved through the use of reproductive technologies and legislation on surrogacy arrangements, civil partnerships and same-sex marriage in the UK, now follows. Different definitions of parenthood and the relational bonds between mothers, fathers and babies are discussed below.

Motherhood and fatherhood

Motherhood and fatherhood

94 Gutteridge (2010, p. 73) has eloquently expressed that:

. . . Motherhood brings with it expectations and dreams; it is a social proclamation of female maturity and an opportunity to pass on our knowledge, skills and stories of womanly experiences. . .

A deep-rooted belief persists in contemporary societies that motherhood reflects ‘

feminine gender identity

’ (Gillespie 2003, p. 122); it delineates women’s social roles and is both sought- after and gratifying for women. By contrast Gutteridge (2010, p. 73) describes fatherhood as merely ‘

a social construct

,’ setting motherhood apart as something physically embodied in women. Whilst women do possess unique biological capacity to house and nurture their devel- oping offspring, during pregnancy and then postnatally through lactation (Murray and Hassall 2009; Coates 2010; Lawrence and Lawrence 2011), reducing fatherhood to a social construct is to deny the significance of the biological and relational investment of men in their children.Draper (2002a,b) found fathers physically involved in pregnancy, through ‘body mediated movements’ (e.g. pregnancy test confirmation and physically feeling the babies’ movements within their mother’s wombs) and medical imaging. A child could be seen as the embodiment of a prior intimate union between a man and a woman – without whom there would be no child. The Fatherhood Institute (2008) note that a father’s initial level of involvement in his baby’s life before, during and after the birth predicts the level and likelihood of his continued involve- ment in the child’s later life. Supportive fathers also foster improved experiences of mothers and babies during birth and in the early postnatal weeks and months. Therefore, midwives should respectfully support both mothers and fathers and provide compassionate care towards them (see Chapter 8:‘Postnatal midwifery care’, where fatherhood is discussed in greater depth). Parental status can be seen as a powerful motivation for people to nurture, protect and provide for children.

Defining parents

Christian ethicist, Professor Oliver O’ Donavan (1984) asserts that the differentiation of the sexes in humankind enables them to engage in natural reproduction:

. . . It is because we stand over against one another, as men and women, as equal but com- plementary members of one human race, that we can, as a race, be fruitful . . .

(O’ Donavan 1984, p. 15)Men and women combine through their biological uniqueness and complementary function to produce offspring. Since the late 20th century there has been an increasing ability to separate reproduction from sexual intercourse between a man and a woman (Ber 2000). This contradicts what Wyatt (2009) describes as the ‘original human design’ (p. 100), in which ‘making love and making babies’ are inseparable, so that the genetic material deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is:

. . . the means by which a unique love between a man and a woman can be converted physi- cally into a baby...

(Wyatt 2009, p. 100)

However, the development of extremely effective and well-tolerated contraceptive methods, from the mid-20th century, concurrent with increasing scientific understanding of reproduction and therapeutic techniques to modify it, have increasingly isolated sexual intercourse from reproduction (Ber 2000; Velde and Pearson 2002). Sexual intercourse can be mainly recreational, with conception being a planned outcome (Benagiano et al. 2010). Furthermore, conception, itself, may now arise devoid of any physical relationship or social connection between ‘

However, the development of extremely effective and well-tolerated contraceptive methods, from the mid-20th century, concurrent with increasing scientific understanding of reproduction and therapeutic techniques to modify it, have increasingly isolated sexual intercourse from reproduction (Ber 2000; Velde and Pearson 2002). Sexual intercourse can be mainly recreational, with conception being a planned outcome (Benagiano et al. 2010). Furthermore, conception, itself, may now arise devoid of any physical relationship or social connection between ‘

mothers

’and ‘

fathers

’. These developments necessitate a re-definition of parenthood (Ber 2000). Griffith 95 (2010) therefore, rightly emphasises the importance of midwives being familiar with current legislation affecting parental status to ensure that they treat the appropriate persons as a child’s parents. These changes have been enacted via the Surrogacy Act 1985, Human Fertilisation and Embryology Acts, 1990, 2008 and legal redefinitions of what constitutes legitimate spousal relationships (Marriage [Same Sex] Couple’s Act 2013). In the following section, these definitionsare discussed.

Genetic, biological and social parents

A genetic parent is one who has provided the gametes – the mature sex cells of males andfemales – which are the source of the fertilised ovum (the zygote) from which the baby devel- ops: the spermatozoon comes from the man and the ovum from the woman (Tiran 2008; Martin 2010). At a minimum each child must have:

(Bottero 2011). However, arguably, the nuclear family was already an established‘norm’ in North

(Bottero 2011). However, arguably, the nuclear family was already an established‘norm’ in North93

West Europe.This portrayal of the traditional nuclear family is tempered with a broader vision of family life that represents the diversity of social arrangements in 21st century Britain. Longstanding vari- ations exist from the notion of nuclear family, for example, the ‘

extended family

’ defined by Bradley and Mendels (1978, p. 381) is ‘

. . . when a household is composed of one person and some other kin in addition to spouse or child.

’ Although the extended family model may be assumed to be more prevalent among certain ethnic groups, in the UK, they exist throughout society. Socioeconomic factors, such as national recession may create more extended family households and somewhat heighten their importance (Byrne et al. 2011). Extended family members, such as the baby’s grandparents, aunts and uncles may prove supportive and influential to parents. Family structures are also shaped by the marital status of the parents. The Office for National Statistics (ONS 2013a) report from the General Lifestyle Survey (GLS) for Great Britain (GB) showed that 49% of women aged over 16 were married; 21% of these women were single, 11% were cohabiting, and 10% were divorced or separated (Table 5.1). ONS (2013b) reported a declining trend in the proportion of first marriages for both partners between 1966 and 2011. A total of 82% of religious marriages were between partners who had never married before in 2011 compared with 60% of civil marriages. However, 88% of couples who married in civil cer- emonies and 78% of those who had religious ceremonies had cohabited prior to marriage (ONS 2013b). When parents remarry, it is considered that ‘

. . . stepchildren and joint biological children who live together . . . belong to a “blended” family

’ (Ginther and Pollak 2004, p. 4). In 2012, about 48% of live births were registered to parents who were either cohabiting, living separately, or who were single parents (ONS 2013c). Therefore midwives can expect to care for married, cohabiting and single mothers, within the varying family contexts. Occasionally, the baby may also be cared for by a single father.

Table 5.1

Marital status of women aged 16 or over in England and Wales 2011 (ONS 2013a)

Percentage of the population of women aged 16 or over

Married49Civil partnership0Cohabiting11Single21Widowed9Divorced7Separated2A more focused discussion of how the meaning of parenthood has evolved through the use of reproductive technologies and legislation on surrogacy arrangements, civil partnerships and same-sex marriage in the UK, now follows. Different definitions of parenthood and the relational bonds between mothers, fathers and babies are discussed below.

Motherhood and fatherhood

Motherhood and fatherhood94 Gutteridge (2010, p. 73) has eloquently expressed that:

. . . Motherhood brings with it expectations and dreams; it is a social proclamation of female maturity and an opportunity to pass on our knowledge, skills and stories of womanly experiences. . .

A deep-rooted belief persists in contemporary societies that motherhood reflects ‘

feminine gender identity

’ (Gillespie 2003, p. 122); it delineates women’s social roles and is both sought- after and gratifying for women. By contrast Gutteridge (2010, p. 73) describes fatherhood as merely ‘

a social construct

,’ setting motherhood apart as something physically embodied in women. Whilst women do possess unique biological capacity to house and nurture their devel- oping offspring, during pregnancy and then postnatally through lactation (Murray and Hassall 2009; Coates 2010; Lawrence and Lawrence 2011), reducing fatherhood to a social construct is to deny the significance of the biological and relational investment of men in their children.Draper (2002a,b) found fathers physically involved in pregnancy, through ‘body mediated movements’ (e.g. pregnancy test confirmation and physically feeling the babies’ movements within their mother’s wombs) and medical imaging. A child could be seen as the embodiment of a prior intimate union between a man and a woman – without whom there would be no child. The Fatherhood Institute (2008) note that a father’s initial level of involvement in his baby’s life before, during and after the birth predicts the level and likelihood of his continued involve- ment in the child’s later life. Supportive fathers also foster improved experiences of mothers and babies during birth and in the early postnatal weeks and months. Therefore, midwives should respectfully support both mothers and fathers and provide compassionate care towards them (see Chapter 8:‘Postnatal midwifery care’, where fatherhood is discussed in greater depth). Parental status can be seen as a powerful motivation for people to nurture, protect and provide for children.

Defining parents

Christian ethicist, Professor Oliver O’ Donavan (1984) asserts that the differentiation of the sexes in humankind enables them to engage in natural reproduction:

. . . It is because we stand over against one another, as men and women, as equal but com- plementary members of one human race, that we can, as a race, be fruitful . . .

(O’ Donavan 1984, p. 15)Men and women combine through their biological uniqueness and complementary function to produce offspring. Since the late 20th century there has been an increasing ability to separate reproduction from sexual intercourse between a man and a woman (Ber 2000). This contradicts what Wyatt (2009) describes as the ‘original human design’ (p. 100), in which ‘making love and making babies’ are inseparable, so that the genetic material deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is:

. . . the means by which a unique love between a man and a woman can be converted physi- cally into a baby...

(Wyatt 2009, p. 100)

However, the development of extremely effective and well-tolerated contraceptive methods, from the mid-20th century, concurrent with increasing scientific understanding of reproduction and therapeutic techniques to modify it, have increasingly isolated sexual intercourse from reproduction (Ber 2000; Velde and Pearson 2002). Sexual intercourse can be mainly recreational, with conception being a planned outcome (Benagiano et al. 2010). Furthermore, conception, itself, may now arise devoid of any physical relationship or social connection between ‘

However, the development of extremely effective and well-tolerated contraceptive methods, from the mid-20th century, concurrent with increasing scientific understanding of reproduction and therapeutic techniques to modify it, have increasingly isolated sexual intercourse from reproduction (Ber 2000; Velde and Pearson 2002). Sexual intercourse can be mainly recreational, with conception being a planned outcome (Benagiano et al. 2010). Furthermore, conception, itself, may now arise devoid of any physical relationship or social connection between ‘mothers

’and ‘

fathers

’. These developments necessitate a re-definition of parenthood (Ber 2000). Griffith 95 (2010) therefore, rightly emphasises the importance of midwives being familiar with current legislation affecting parental status to ensure that they treat the appropriate persons as a child’s parents. These changes have been enacted via the Surrogacy Act 1985, Human Fertilisation and Embryology Acts, 1990, 2008 and legal redefinitions of what constitutes legitimate spousal relationships (Marriage [Same Sex] Couple’s Act 2013). In the following section, these definitionsare discussed.

Genetic, biological and social parents

A genetic parent is one who has provided the gametes – the mature sex cells of males andfemales – which are the source of the fertilised ovum (the zygote) from which the baby devel- ops: the spermatozoon comes from the man and the ovum from the woman (Tiran 2008; Martin 2010). At a minimum each child must have:

a genetic mother

a genetic father.The exceptions to this rule would be reproductive cloning, currently illegal in most countries and use of mitochondrial replacement therapy (Human Reproductive Cloning Act, 2001; Wyatt, 2009; Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority [HFEA], 2013). Traditionally, parents would have been in a social contract of marriage and the child would have been carried in the womb of his genetic mother, being the progeny of both his genetic mother and genetic father, who would also be responsible for his nurture (see Figure 5.3).A

biological parent

is one with whom the child has a direct biological connection; either through their gametes, or through being carried in a woman’s uterus during pregnancy (Ber

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3

A traditional nuclear family: husband, wife and baby.

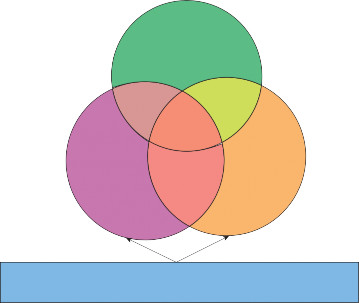

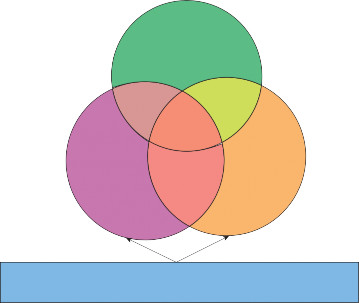

Social mother

Social mother

96

96

Genetic mother

Traditional mother

Gestational mother

Biological mother

May be applied to either the genetic or gestational mothers

Figure 5.4

Venn diagram illustrating the division of social and biological mothering in gestational surrogacy (Ber 2000; Erin & Harris 1991; FIGO Committee for the Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women’s Health 2008).2000). Figures 5.4–5.9 are essentially the same Venn diagram used to illustrate different facets of the mothering role as it exists today. Each diagram emphasises a different aspect of mother- hood. A

biological mother

(see Figure 5.4) may, therefore, be considered to be:

biological parent

is one with whom the child has a direct biological connection; either through their gametes, or through being carried in a woman’s uterus during pregnancy (Ber

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3A traditional nuclear family: husband, wife and baby.

Social mother

Social mother 96

96Genetic mother

Traditional mother

Gestational mother

Biological mother

May be applied to either the genetic or gestational mothers

Figure 5.4

Venn diagram illustrating the division of social and biological mothering in gestational surrogacy (Ber 2000; Erin & Harris 1991; FIGO Committee for the Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women’s Health 2008).2000). Figures 5.4–5.9 are essentially the same Venn diagram used to illustrate different facets of the mothering role as it exists today. Each diagram emphasises a different aspect of mother- hood. A

biological mother

(see Figure 5.4) may, therefore, be considered to be:

Other books

The Lost Slipper (Fairytale Shifter Book 3) by Alexa Riley

Dead Beautiful by Yvonne Woon

Obsessed by G. H. Ephron

Lipstick & Stilettos by Young, Tarra

Breanna by Karen Nichols

Written in Stone by Rosanne Parry

Snowbound With The Bear (Bear Creek Clan 4) by Harmony Raines

MMF BISEXUAL ROMANCE: Phoenix Running by Nicole Stewart

Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch by Miller, Henry

Coming Attractions by Bobbi Marolt