Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (86 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

4.21Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Box 9.2 Skin care product guidance

Soap should be avoided as it disrupts the skin’s natural lipid barrier.

When skin cleansers and products are gradually introduced, they should be free from sulphates,colours and perfumes.

Avoid the use of cloths or sponges as these may rub and damage the skin.

Hand washing the baby or using cotton wool or a natural sponge is gentler.

Baby wipes should be avoided in the first month. Once gradually introduced, they should bealcohol and fragrance free.

It is safer to bath the newborn in plain water for at least the first month of life.

Oils containing perfume or dye should not be used and nut and petroleum-based oils shouldbe avoided.

199(Trotter 2010)

199(Trotter 2010)

Nappy care

Gentle cleansing of the nappy area at each nappy change with plain, warm water and cotton wool is key to preventing or at least minimising the risk of nappy rash. Trotter (2010) recom- mends washing the nappy area with warm water and the application of a thin layer of a barrier cream. Trotter (2008) suggests any barrier cream should be fragrance and antiseptic free. As noted in Box 9.3, the use of baby wipes are not recommended for at least the first month of life (Trotter 2008; 2010).

Cord care

The evidence available currently clearly suggests that the best method of cord care is to keep it as clean and dry as possible without the use of sprays, creams and powders as these may well inhibit rather than assist natural separation (Trotter 2010; Hughes 2011; Zupan et al. 2012). Hand washing before handling the cord is essential to minimise the risk of colonisation by pathogens and keeping the cord free of the nappy area to prevent contamination by urine or faeces. A small amount of moisture at the base of the cord is normal, and should not be mistaken for infection (Trotter 2010).Parents are often nervous of the umbilical cord stump and should be reassured about drying it carefully when bathing the baby. They should also be provided with information regarding the normal process of separation, both to prevent unnecessary worrying and to allow them to recognise potential infection.

Jaundice

Physiological jaundice

Physiological jaundice is a common newborn problem that rarely needs active intervention, although it can sometimes require investigation and active management (Gordan and Lomax (2011). The presence of certain risk factors can increase the severity and frequency of physiologi- cal jaundice, for example; low birth weight and prematurity (Gordan and Lomax 2011). It arises due to the immaturity of the liver at a time when there is increased production of bilirubin due to the breakdown of excess red blood cells. In utero the fetus needs extra red blood cells to200

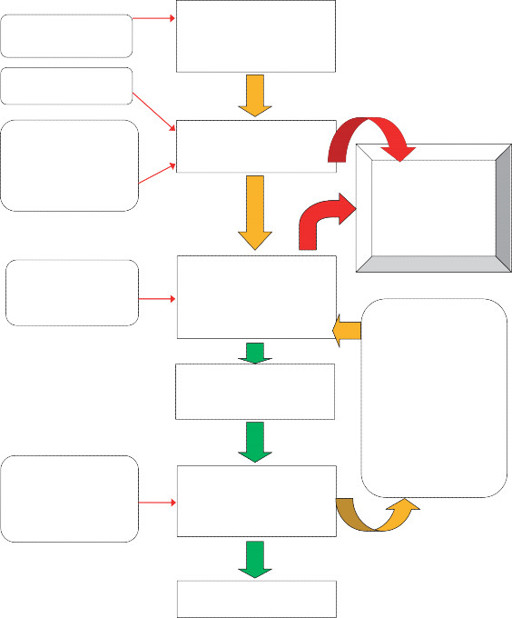

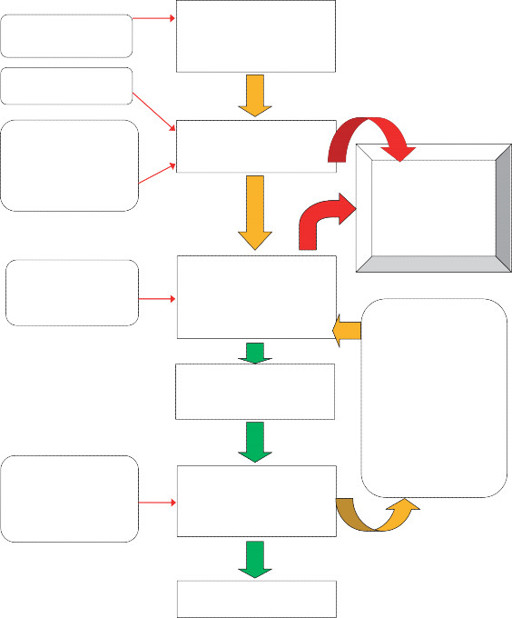

accommodate the relatively low oxygenation provided by the placenta, but once delivered and breathing spontaneously a reduction of approximately 20% is made to bring the cell count to normal limits. The liver is responsible for bilirubin metabolism and its immaturity in the neonatal period means that the process is inefficient leading to circulating bilirubin being deposited in the subcutaneous fat – it is this deposition under the skin that causes the yellow discolouration of jaundice. Bilirubin processed by the liver changes from being fat soluble (unconjugated) to water soluble (conjugated) and is passed into the gastrointestinal system via the gall bladder. Some conjugated bilirubin will be absorbed via the gut wall and will be excreted via the kidneys giving the urine its characteristic straw colour. The rest is excreted in the faeces. In the newborn, however, the intestinal process is impeded by the lack of gut bacteria and relatively slow peri- stalsis and this results in conjugated bilirubin being converted back to unconjugated and rea- bsorbed to be returned to the liver. This process is illustrated in Figure 9.7. Physiological jaundice generally occurs around the third after birth and peaks around the fourth and fifth day resolving by the seventh to tenth day (England 2010b). Visible early jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is strongly associated with haematological disease such as rhesus incompatibility or red cell abnormality.Physiological jaundice is not usually dangerous in itself, as it is self-limiting in that once the reduction in red blood cells has been achieved, the production of bilirubin will return to levels the liver can manage effectively. However, there is always a risk that it masks a more pathologi- cal process associated with liver or haematological disorder or congenital abnormality. It is vital therefore that any jaundice in the newborn is taken seriously and that babies who may be at greater risk from complications are identified. NICE (2010) recommend a pathway approach to the care of babies with visible jaundice and that all such babies have the serum bilirubin meas- ured. The measurement of serum bilirubin in jaundiced babies is important as high levels can result in a condition known as kernicterus or bilirubin encephalopathy, which will have neu- rodevelopment consequences for the affected baby. Levels of bilirubin which do not cause encephalopathy can nevertheless cause auditory impairment.Levels of serum bilirubin can be measured by means of a capillary blood sample (obtained by a heel prick) or by transcutaneous bilirubinometer. Although the latter is non-invasive, it is an expensive piece of equipment and midwives need training in its use; therefore this method may not be available in all units. A reading deemed high on a bilirubinometer would necessitate a blood test to provide a more accurate clinical picture. NICE (2010) guidance provides a graph with regard to levels of bilirubin that require treatment in the term baby to better standardise initiation of treatment and thereby improve outcomes for significantly affected babies. Treat- ment, should it be required, is to use blue-green light to break down bilirubin in the skin. The blue-green light can either be delivered by an overhead phototherapy unit placed over the cot or incubator in which the baby is nursed, naked except for a nappy and eye protection, or a slightly less effective biliblanket which can be wrapped around the baby who does not need eye protection from this method.

accommodate the relatively low oxygenation provided by the placenta, but once delivered and breathing spontaneously a reduction of approximately 20% is made to bring the cell count to normal limits. The liver is responsible for bilirubin metabolism and its immaturity in the neonatal period means that the process is inefficient leading to circulating bilirubin being deposited in the subcutaneous fat – it is this deposition under the skin that causes the yellow discolouration of jaundice. Bilirubin processed by the liver changes from being fat soluble (unconjugated) to water soluble (conjugated) and is passed into the gastrointestinal system via the gall bladder. Some conjugated bilirubin will be absorbed via the gut wall and will be excreted via the kidneys giving the urine its characteristic straw colour. The rest is excreted in the faeces. In the newborn, however, the intestinal process is impeded by the lack of gut bacteria and relatively slow peri- stalsis and this results in conjugated bilirubin being converted back to unconjugated and rea- bsorbed to be returned to the liver. This process is illustrated in Figure 9.7. Physiological jaundice generally occurs around the third after birth and peaks around the fourth and fifth day resolving by the seventh to tenth day (England 2010b). Visible early jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is strongly associated with haematological disease such as rhesus incompatibility or red cell abnormality.Physiological jaundice is not usually dangerous in itself, as it is self-limiting in that once the reduction in red blood cells has been achieved, the production of bilirubin will return to levels the liver can manage effectively. However, there is always a risk that it masks a more pathologi- cal process associated with liver or haematological disorder or congenital abnormality. It is vital therefore that any jaundice in the newborn is taken seriously and that babies who may be at greater risk from complications are identified. NICE (2010) recommend a pathway approach to the care of babies with visible jaundice and that all such babies have the serum bilirubin meas- ured. The measurement of serum bilirubin in jaundiced babies is important as high levels can result in a condition known as kernicterus or bilirubin encephalopathy, which will have neu- rodevelopment consequences for the affected baby. Levels of bilirubin which do not cause encephalopathy can nevertheless cause auditory impairment.Levels of serum bilirubin can be measured by means of a capillary blood sample (obtained by a heel prick) or by transcutaneous bilirubinometer. Although the latter is non-invasive, it is an expensive piece of equipment and midwives need training in its use; therefore this method may not be available in all units. A reading deemed high on a bilirubinometer would necessitate a blood test to provide a more accurate clinical picture. NICE (2010) guidance provides a graph with regard to levels of bilirubin that require treatment in the term baby to better standardise initiation of treatment and thereby improve outcomes for significantly affected babies. Treat- ment, should it be required, is to use blue-green light to break down bilirubin in the skin. The blue-green light can either be delivered by an overhead phototherapy unit placed over the cot or incubator in which the baby is nursed, naked except for a nappy and eye protection, or a slightly less effective biliblanket which can be wrapped around the baby who does not need eye protection from this method.

Breastfeeding jaundice

Some babies who are breastfed may demonstrate higher bilirubin levels than formula-fed infants, and their jaundice may be more prolonged. This is thought to be due to the lower fluid and calorific intake associated with breastfeeding in the first few days of life which increases entero-hepatic shunting. The slower colonisation of the gut with bacteria in breastfed babies also contributes to higher bilirubin levels. It is thought that this may occur to utilise the antioxi- dant properties of unconjugated bilirubin and provided that the baby is feeding well and gaining sufficient calories and the jaundice is monitored carefully, there will be no adverseHigh red blood cell count in utero

Breakdown of red blood cells in reticulo-endothelial system produces

Breakdown of red blood cells in reticulo-endothelial system produces

unconjugated bilirubin

Low serum albumin in early neonatal periodSerum albumin binding capacity reduced by infection, hypoglycaemia, prematurity, asphyxia, acidosis, cold stress and drug treatmentsUnconjugated bilirubin is transported to liver bound to serum albuminExcess unconjugated bilirubin deposited insubcutaneous fat causing yellow skin colouration of

jaundice

201Immaturity of liver reduces ability to convert bilirubin from unconjugated to conjugated

201Immaturity of liver reduces ability to convert bilirubin from unconjugated to conjugated

Fat soluble

unconjugated bilirubin converted to

water soluble conjugated bilirubin

by liverConjugated bilirubin excreted into duodenum in bile via the gall bladderConjugated bilirubin is converted back to unconjugated bilirubin by means of hydrolysis which causes absorption by bowel and re-entry of unconjugated bilirubin into blood streamand thence back to the liver.This is known as

enterohepatic circulation

Sterile bowel and slow peristalsis of newborns reduce conversion of bilirubin to stercobilinogen and urobilinogenConjugated bilirubin converted to

stercobilinogen and urobilinogen

by bacteria in small bowelExcretion in faeces and via kidneys in urine

Figure 9.7

Neonatal bilirubin metabolism.effects. It is certainly no reason for changing the feeding method and mothers should be pro- vided with support and information in relation to their breastfeeding.202

Breastmilk jaundice syndrome

This jaundice is later in onset than either physiological or breastfeeding types, occurring around 4 days postnatal and peaking at 10–15 days. It is thought that this type of jaundice is related to be due to specific factors in the breastmilk and can last for between 3–12 weeks. Babies should be medically assessed to rule out pathological causes of the jaundice and levels should be monitored, but the syndrome is rarely associated with complications. Again there is no evidence to support cessation of breastfeeding.

This jaundice is later in onset than either physiological or breastfeeding types, occurring around 4 days postnatal and peaking at 10–15 days. It is thought that this type of jaundice is related to be due to specific factors in the breastmilk and can last for between 3–12 weeks. Babies should be medically assessed to rule out pathological causes of the jaundice and levels should be monitored, but the syndrome is rarely associated with complications. Again there is no evidence to support cessation of breastfeeding.

Neonatal screening

It is the role of the midwife to ensure that women are provided with accurate informationregarding newborn screening tests so that they can make informed choices for their babies. This information giving should commence antenatally but should also be provided postnatally in a timely fashion to allow screening tests to be carried out at the optimum time.

The blood spot test

This test is offered to all mothers and should ideally be taken on day 5 (taking the day of delivery as day 0) (UK Newborn Screening Centre, 2012) but should be within 5–8 days of birth in term infants who have been feeding normally (there are specific guidelines for preterm or sick infants who have not been enterally feeding). Recommendations from the UK Newborn Screening Centre (UK NSC) suggest that it provides screening for:

199(Trotter 2010)

199(Trotter 2010)Nappy care

Gentle cleansing of the nappy area at each nappy change with plain, warm water and cotton wool is key to preventing or at least minimising the risk of nappy rash. Trotter (2010) recom- mends washing the nappy area with warm water and the application of a thin layer of a barrier cream. Trotter (2008) suggests any barrier cream should be fragrance and antiseptic free. As noted in Box 9.3, the use of baby wipes are not recommended for at least the first month of life (Trotter 2008; 2010).

Cord care

The evidence available currently clearly suggests that the best method of cord care is to keep it as clean and dry as possible without the use of sprays, creams and powders as these may well inhibit rather than assist natural separation (Trotter 2010; Hughes 2011; Zupan et al. 2012). Hand washing before handling the cord is essential to minimise the risk of colonisation by pathogens and keeping the cord free of the nappy area to prevent contamination by urine or faeces. A small amount of moisture at the base of the cord is normal, and should not be mistaken for infection (Trotter 2010).Parents are often nervous of the umbilical cord stump and should be reassured about drying it carefully when bathing the baby. They should also be provided with information regarding the normal process of separation, both to prevent unnecessary worrying and to allow them to recognise potential infection.

Jaundice

Physiological jaundice

Physiological jaundice is a common newborn problem that rarely needs active intervention, although it can sometimes require investigation and active management (Gordan and Lomax (2011). The presence of certain risk factors can increase the severity and frequency of physiologi- cal jaundice, for example; low birth weight and prematurity (Gordan and Lomax 2011). It arises due to the immaturity of the liver at a time when there is increased production of bilirubin due to the breakdown of excess red blood cells. In utero the fetus needs extra red blood cells to200

accommodate the relatively low oxygenation provided by the placenta, but once delivered and breathing spontaneously a reduction of approximately 20% is made to bring the cell count to normal limits. The liver is responsible for bilirubin metabolism and its immaturity in the neonatal period means that the process is inefficient leading to circulating bilirubin being deposited in the subcutaneous fat – it is this deposition under the skin that causes the yellow discolouration of jaundice. Bilirubin processed by the liver changes from being fat soluble (unconjugated) to water soluble (conjugated) and is passed into the gastrointestinal system via the gall bladder. Some conjugated bilirubin will be absorbed via the gut wall and will be excreted via the kidneys giving the urine its characteristic straw colour. The rest is excreted in the faeces. In the newborn, however, the intestinal process is impeded by the lack of gut bacteria and relatively slow peri- stalsis and this results in conjugated bilirubin being converted back to unconjugated and rea- bsorbed to be returned to the liver. This process is illustrated in Figure 9.7. Physiological jaundice generally occurs around the third after birth and peaks around the fourth and fifth day resolving by the seventh to tenth day (England 2010b). Visible early jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is strongly associated with haematological disease such as rhesus incompatibility or red cell abnormality.Physiological jaundice is not usually dangerous in itself, as it is self-limiting in that once the reduction in red blood cells has been achieved, the production of bilirubin will return to levels the liver can manage effectively. However, there is always a risk that it masks a more pathologi- cal process associated with liver or haematological disorder or congenital abnormality. It is vital therefore that any jaundice in the newborn is taken seriously and that babies who may be at greater risk from complications are identified. NICE (2010) recommend a pathway approach to the care of babies with visible jaundice and that all such babies have the serum bilirubin meas- ured. The measurement of serum bilirubin in jaundiced babies is important as high levels can result in a condition known as kernicterus or bilirubin encephalopathy, which will have neu- rodevelopment consequences for the affected baby. Levels of bilirubin which do not cause encephalopathy can nevertheless cause auditory impairment.Levels of serum bilirubin can be measured by means of a capillary blood sample (obtained by a heel prick) or by transcutaneous bilirubinometer. Although the latter is non-invasive, it is an expensive piece of equipment and midwives need training in its use; therefore this method may not be available in all units. A reading deemed high on a bilirubinometer would necessitate a blood test to provide a more accurate clinical picture. NICE (2010) guidance provides a graph with regard to levels of bilirubin that require treatment in the term baby to better standardise initiation of treatment and thereby improve outcomes for significantly affected babies. Treat- ment, should it be required, is to use blue-green light to break down bilirubin in the skin. The blue-green light can either be delivered by an overhead phototherapy unit placed over the cot or incubator in which the baby is nursed, naked except for a nappy and eye protection, or a slightly less effective biliblanket which can be wrapped around the baby who does not need eye protection from this method.

accommodate the relatively low oxygenation provided by the placenta, but once delivered and breathing spontaneously a reduction of approximately 20% is made to bring the cell count to normal limits. The liver is responsible for bilirubin metabolism and its immaturity in the neonatal period means that the process is inefficient leading to circulating bilirubin being deposited in the subcutaneous fat – it is this deposition under the skin that causes the yellow discolouration of jaundice. Bilirubin processed by the liver changes from being fat soluble (unconjugated) to water soluble (conjugated) and is passed into the gastrointestinal system via the gall bladder. Some conjugated bilirubin will be absorbed via the gut wall and will be excreted via the kidneys giving the urine its characteristic straw colour. The rest is excreted in the faeces. In the newborn, however, the intestinal process is impeded by the lack of gut bacteria and relatively slow peri- stalsis and this results in conjugated bilirubin being converted back to unconjugated and rea- bsorbed to be returned to the liver. This process is illustrated in Figure 9.7. Physiological jaundice generally occurs around the third after birth and peaks around the fourth and fifth day resolving by the seventh to tenth day (England 2010b). Visible early jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is strongly associated with haematological disease such as rhesus incompatibility or red cell abnormality.Physiological jaundice is not usually dangerous in itself, as it is self-limiting in that once the reduction in red blood cells has been achieved, the production of bilirubin will return to levels the liver can manage effectively. However, there is always a risk that it masks a more pathologi- cal process associated with liver or haematological disorder or congenital abnormality. It is vital therefore that any jaundice in the newborn is taken seriously and that babies who may be at greater risk from complications are identified. NICE (2010) recommend a pathway approach to the care of babies with visible jaundice and that all such babies have the serum bilirubin meas- ured. The measurement of serum bilirubin in jaundiced babies is important as high levels can result in a condition known as kernicterus or bilirubin encephalopathy, which will have neu- rodevelopment consequences for the affected baby. Levels of bilirubin which do not cause encephalopathy can nevertheless cause auditory impairment.Levels of serum bilirubin can be measured by means of a capillary blood sample (obtained by a heel prick) or by transcutaneous bilirubinometer. Although the latter is non-invasive, it is an expensive piece of equipment and midwives need training in its use; therefore this method may not be available in all units. A reading deemed high on a bilirubinometer would necessitate a blood test to provide a more accurate clinical picture. NICE (2010) guidance provides a graph with regard to levels of bilirubin that require treatment in the term baby to better standardise initiation of treatment and thereby improve outcomes for significantly affected babies. Treat- ment, should it be required, is to use blue-green light to break down bilirubin in the skin. The blue-green light can either be delivered by an overhead phototherapy unit placed over the cot or incubator in which the baby is nursed, naked except for a nappy and eye protection, or a slightly less effective biliblanket which can be wrapped around the baby who does not need eye protection from this method.Breastfeeding jaundice

Some babies who are breastfed may demonstrate higher bilirubin levels than formula-fed infants, and their jaundice may be more prolonged. This is thought to be due to the lower fluid and calorific intake associated with breastfeeding in the first few days of life which increases entero-hepatic shunting. The slower colonisation of the gut with bacteria in breastfed babies also contributes to higher bilirubin levels. It is thought that this may occur to utilise the antioxi- dant properties of unconjugated bilirubin and provided that the baby is feeding well and gaining sufficient calories and the jaundice is monitored carefully, there will be no adverseHigh red blood cell count in utero

Breakdown of red blood cells in reticulo-endothelial system produces

Breakdown of red blood cells in reticulo-endothelial system producesunconjugated bilirubin

Low serum albumin in early neonatal periodSerum albumin binding capacity reduced by infection, hypoglycaemia, prematurity, asphyxia, acidosis, cold stress and drug treatmentsUnconjugated bilirubin is transported to liver bound to serum albuminExcess unconjugated bilirubin deposited insubcutaneous fat causing yellow skin colouration of

jaundice

201Immaturity of liver reduces ability to convert bilirubin from unconjugated to conjugated

201Immaturity of liver reduces ability to convert bilirubin from unconjugated to conjugatedFat soluble

unconjugated bilirubin converted to

water soluble conjugated bilirubin

by liverConjugated bilirubin excreted into duodenum in bile via the gall bladderConjugated bilirubin is converted back to unconjugated bilirubin by means of hydrolysis which causes absorption by bowel and re-entry of unconjugated bilirubin into blood streamand thence back to the liver.This is known as

enterohepatic circulation

Sterile bowel and slow peristalsis of newborns reduce conversion of bilirubin to stercobilinogen and urobilinogenConjugated bilirubin converted to

stercobilinogen and urobilinogen

by bacteria in small bowelExcretion in faeces and via kidneys in urine

Figure 9.7

Neonatal bilirubin metabolism.effects. It is certainly no reason for changing the feeding method and mothers should be pro- vided with support and information in relation to their breastfeeding.202

Breastmilk jaundice syndrome

This jaundice is later in onset than either physiological or breastfeeding types, occurring around 4 days postnatal and peaking at 10–15 days. It is thought that this type of jaundice is related to be due to specific factors in the breastmilk and can last for between 3–12 weeks. Babies should be medically assessed to rule out pathological causes of the jaundice and levels should be monitored, but the syndrome is rarely associated with complications. Again there is no evidence to support cessation of breastfeeding.

This jaundice is later in onset than either physiological or breastfeeding types, occurring around 4 days postnatal and peaking at 10–15 days. It is thought that this type of jaundice is related to be due to specific factors in the breastmilk and can last for between 3–12 weeks. Babies should be medically assessed to rule out pathological causes of the jaundice and levels should be monitored, but the syndrome is rarely associated with complications. Again there is no evidence to support cessation of breastfeeding.Neonatal screening

It is the role of the midwife to ensure that women are provided with accurate informationregarding newborn screening tests so that they can make informed choices for their babies. This information giving should commence antenatally but should also be provided postnatally in a timely fashion to allow screening tests to be carried out at the optimum time.

The blood spot test

This test is offered to all mothers and should ideally be taken on day 5 (taking the day of delivery as day 0) (UK Newborn Screening Centre, 2012) but should be within 5–8 days of birth in term infants who have been feeding normally (there are specific guidelines for preterm or sick infants who have not been enterally feeding). Recommendations from the UK Newborn Screening Centre (UK NSC) suggest that it provides screening for:

Other books

Tommy: A Bad Boy Motorcycle Romance by Wallace, R.S.

My Two Men of the House 3: Kevin and Michael by Cassandra Zara

Party of One by Michael Harris

Townie by Andre Dubus III

Leon Uris by Redemption

Made for Sin by Stacia Kane

Distracted by Madeline Sloane

Manhattan 62 by Nadelson, Reggie

A Dark Grave (Elysium Chronicles, .5) by J.A. Souders

The Firebrand Legacy by T.K. Kiser