Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (91 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

3.62Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The literature indicates the decision to initiate and continue breastfeeding is much more complex than simply the practicalities of providing nutrition to the baby; rather it is influenced by a social and cultural construct. Many women appear to have the understanding that ‘

breast is best

‘, but many other factors impinge on the decision to breastfeed (Burns et al. 2010). Some mothers, particularly in Western societies, view formula feeding as the more practical and con- venient option (Lee 2007; Brown et al. 2011). However, the experiences of some mothers who have chosen to formula feed have been reported as being negative, with emotions of anger, guilt and a sense of failure as a mother (Lakshman et al. 2009; Guyer et al. 2012). Mothers may experience conflict through a perceived moral duty to breastfeed viewed as good mothering, and the cultural norms of formula feeding, requiring less intensive mothering and a quicker independence of the baby. It is questionable how useful the ‘

breast is best

‘ slogan really is in supporting mothers in their choice of infant feeding.

Health professionals and care givers need to understand the complexities, and meanings attributed to the mothers’ infant feeding intentions at different times during childbearing. It is argued by Sheehan et al. (2010) that care needs to be individualised to suit women’s needs rather than being embedded in the dominant ‘

breast is best

‘ message, with the needs of the infant superseding that of the mother. It has been suggested that the focus on the productivity of breastfeeding; the mother supplying a product based on a baby’s demand, implies a dis- embodied experience likely to cause doubt in the mother’s ability to produce enough milk (Dykes 2005; Dykes and Flacking 2010). Similarly, the language used by health professionals could inadvertently undermine a woman’s confidence and natural mothering ability, with the focus on frequency, duration and timings of breastfeeds. Teaching and observing techniques guided by hospital policies may give the impression that breastfeeding is difficult, prone to problems and supports the ‘

I’ll give it a go

‘ culture reinforced by the formula companies adver- tising their products (Marsden and Abayomi 2012). Culturally, shared knowledge of breastfeed- ing has been lost within communities. It has become a health behaviour that needs to be promoted, taught, observed, learned and guided by healthcare professionals, rather than it being an accepted cultural norm as a result of shared learning and development of tacit knowledge.

Activity 10.1

Go to these newspaper articles and think about what they say about society’s views of

breastfeeding.

[Available online] http://www.theguardian.com/media/2008/dec/30/facebook-breastfeeding

-ban and http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2356952/Breastfeeding-mother-humiliated

-train-conductor-told-to-toilet-feed-daughter.html?ITO=1490&ns_mchannel=rss&ns

_campaign=1490

Activity 10.2

Find magazines aimed at pregnant women and mothers and think about what the images say

about infant feeding. How do you think they might influence women and families in their decisions?

Supporting mothers to initiate breastfeeding and continue exclusive breastfeeding for longer

Focusing simply on the biological benefits of breastfeeding can cause many dilemmas for women, increasing their susceptibility to psychological ill health affecting the maternal-infant bond (Guyer et al. 2012). It is important for health professionals and supporters involved in the care of the woman and families, to apply a bio-psycho-social approach in assessing individual needs, being sensitive to individual values and beliefs whilst promoting and supporting breast- feeding. Health professionals could improve a mothers’ experience by paying more attention to emotional issues and setting realistic achievable goals, rather than focusing on the technicalities of breastfeeding. A family-centred approach should be achieved by listening, respecting values and encouraging breastfeeding for as long as the mother feels she can, celebrating her indi- vidual success and achievable goals.

The way breastfeeding works

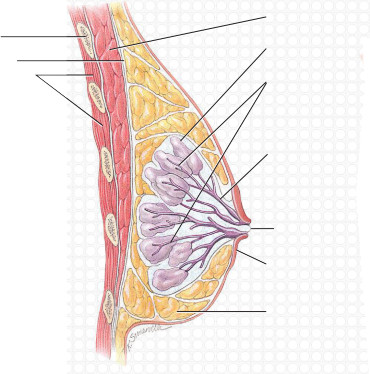

For midwives and other health professionals to feel confident in supporting mothers to breast-

feed, an understanding of the physiology of the breast and lactation is important. Figure 10.1 illustrates the physiology and anatomy of the breast.

Physiology of lactation

Lactogenesis I

Lactogenesis I begins during the second trimester of pregnancy and is characterised by the proliferation of the ductal and alveoli tissue within the breast in preparation for milk production at term. These developments are directed by the circulating hormones of pregnancy, namely oestrogen, progesterone and human placental lactogen (HPL). Lactocytes (milk producing cells), begin to synthesise small amounts of early milk (colostrum) from components: glucose, amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins and minerals, diffusing from the surrounding blood capillary network across the alveolar cell membrane (Kent 2007). The high levels of progesterone, oes- trogen and HPL also serve to inhibit the release of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland during pregnancy, thus preventing the onset of copious milk production at this stage (Lawrence and Lawrence 2011).

Lactogenesis II

Lactogenesis II is hormone driven under endocrine control and is triggered by the rapid fall in circulating oestrogen, progesterone and HPL, following the expulsion of the placenta and membranes (Lawrence and Lawrence 2011). This allows prolactin secretions to be released in response to milk removal by frequent and effective breastfeeding or breast expression in the first few postnatal days. Close skin-to-skin contact, and stimulation of the nipple tissue by the baby’s tongue just prior to attachment to the breast, results in a neuro-hormonal reflex called the milk ejection reflex (MER), commonly known as the ‘let-down reflex’ which some mothers

213

Rib

Fascia

Intercostal Muscles

Pectoralis muscle Lobes containing alveoli Ductules

Lactiferous duct

214

Nipple opening Areola

Adipose tissue

Sagittal section of lactating breast

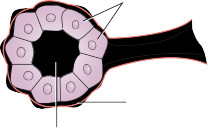

Magnified view of alveoli

Acini secretory cells

Myoepithelial cell

Ductule

Figure 10.1

Anatomy of the breast. Source: Adapted from Tortora and Derrickson 2009, Figure 28.6, p. 1088, with permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

feel as a tingling sensation. Oxytocin is released into the circulation from the posterior pituitary gland in pulsatile waves, causing the myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli to contract, pushing the milk out into the ductal system towards the nipple pore openings (Lawrence and Lawrence 2011). Lactogenesis II is also dependant on a delicate balance of insulin, thyroxin and adrenal cortisol and blood supply (Kent 2007). The combination of frequent milk removal and subsequent prolactin releases ensures that the prolactin receptor cells within the alveoli of the breast are triggered, i.e. ‘switched on’ and copious milk production ensues. The mother

Other books

Dark Union (The Descent Series) by Reine, SM

The Armored Doctor (Curiosity Chronicles Book 2) by Ava Morgan

Cowboy Kisses by Diane Michele Crawford

The Black Door by Collin Wilcox

The Emperor's Edge by Buroker, Lindsay

His Cure For Magic (Book 2) by M.R. Forbes

Death's Academy by Bast, Michael

Secrets & Lies: Two Short Stories by Keplinger, Kody

Cupid's Christmas by Bette Lee Crosby