Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (29 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

The Deir el-Bahri bay had for a long time been revered as a holy place associated with the cult of the mother-goddess Hathor in her role as Goddess of the West or Chieftainess of Thebes. For this reason it had been chosen as the location of the mortuary temple of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II, the Theban founder of the Middle Kingdom. Mentuhotep II had been the epitome of a successful Egyptian king. He had united Egypt at the end of the First Intermediate Period, instigated successful campaigns against the traditional enemies to the north and south, established a new capital at Thebes and, throughout his 51-year reign, undertaken prolific building works, including the restoration of ancient monuments and the construction of new buildings. The parallel between his glorious reign and that of Tuthmosis I must have been obvious and it is not surprising that Hatchepsut, ever prone to hero-worship Tuthmosis I, held her ‘father Mentuhotep II’

14

in special regard.

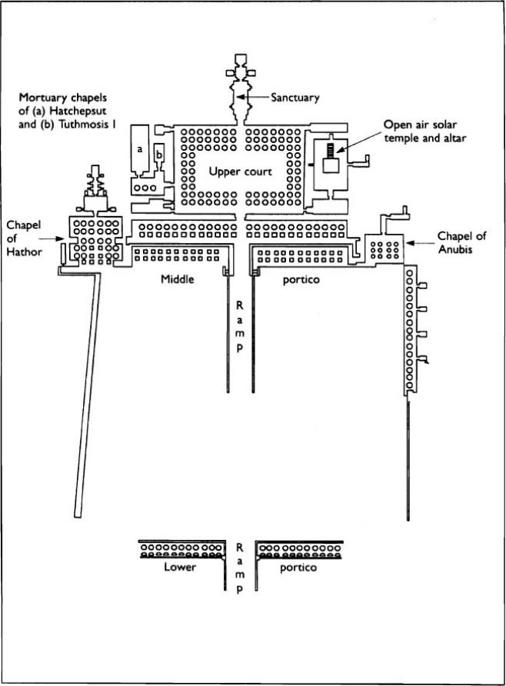

Fig. 6.3 Plan of

Djeser-Djeseru

Mentuhotep had modelled his funerary monument, ‘Glorious are the Seats of Nebhepetre’, on the Old Kingdom pyramid complexes, and his was the first temple in Egypt to utilize terraces so that different parts of the building were constructed at different levels with the most sacred part of the temple cut directly into the Theban mountain. Unfortunately, the temple was ruined in antiquity and its original plan is now uncertain, although it seems that the sequence of terraces rose to a solid mastaba- or pyramid-like core. It was these terraces which first inspired the architects of Tuthmosis II, the initial 18th Dynasty developer of the site, and the original plans for the New Kingdom temple adhered fairly faithfully to the Middle Kingdom model. However, with the untimely death of Tuthmosis II, the building works were halted, the plans were redrawn on a far more ambitious scale, and

Djeser-Djeseru

became very much Hatchepsut's own monument, an architectural masterpiece providing a superb example of a manmade object designed to fit perfectly into its natural setting. The beauties of

Djeser-Djeseru

have inspired many egyptologists to flights of purple prose:

It is built at the base of the rugged Theban cliffs, and commands the plain in magnificent fashion; its white colonnades rising, terrace above terrace, until it is backed by the golden living rock. The ivory white walls of courts, side chambers and colonnades, have polished surfaces which give an alabaster-like effect. They are carved with a fine art, figures and hieroglyphs being filled in with rich yellow colour, the glow of which against the white gives an effect of warmth and beauty quite indescribable.

15

Few who have enjoyed the privilege of visiting Deir el-Bahri would argue with this assessment, and today

Djeser-Djeseru

remains beyond doubt one of the most beautiful buildings in the world. It certainly occupies a unique place in the history of Egyptian architecture, and indeed the columned porticoes which provide a striking contrast of light and shade across the front of the building appear to many modern eyes more Greek than Egyptian in style, provoking anachronistic but flattering comparisons with classical temple architecture in its most pure form. Only Winlock, the long-term excavator of

Djeser-Djeseru

, has gone on record as expressing his doubts about the magnificence of the edifice, and even he reserves his criticism for its construction rather than its design:

Unquestionably, when it was completed the building was far more imposing than its eleventh dynasty model, and its plan had been adapted to fit its magnificent surroundings in a wholly masterful way. But whenever we have had occasion to examine its shoddy, jerry-built foundations, we have had an unpleasant feeling of sham behind all this impressiveness which up to that time had not been especially characteristic of Egyptian architects. Possibly Senenmut was a victim of necessity and speed was required of him – or perhaps there is some more venal explanation.

16

The architect of this masterpiece is generally assumed to be Hatchepsut's favourite Senenmut, who numbers amongst his titles ‘Controller of Works in

Djeser-Djeseru

’. However Senenmut never specifically claims the title of architect, a strange omission for one not normally shy of listing his own accomplishments, and it seems that the Chief Treasurer Djehuty, who ‘… acted as chief, giving directions, I led the craftsman to work in the works of

Djeser-Djeseru

’, may well have played a major part in its development. Other high-ranking courtiers, including the Vizier (unnamed, but almost certainly Hapuseneb who is credited with the building of Hatchepsut's tomb) and the Second Prophet of Amen, Puyemre, also had some involvement in its construction; all of these officials are known to have been the recipients of so-called ‘name stones’, building blocks donated to the construction project by the ordinary citizens of Thebes. These roughly cut stones, recovered from the foundations of the Valley temple, all bear the cartouche of Maatkare plus an additional hieratic inscription detailing the date that they were sent to the building site, the name of the sender and the name of the recipient. Further bricks recovered from the Valley temple are stamped with the cartouches of Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis I, which appear side by side.

The name of Tuthmosis I is also to be found amongst the engraved scarabs which formed a part of the temple foundation deposits. These deposits – offerings intended to preserve the name of the builder and to ensure good luck in the founding of the temple – were buried with ceremony in small mud-brick-lined pits at every important point around the boundaries of the temple and its grounds.

17

They included a mixture of amulets, scarabs, foods, perfumes and miniature models of the tools which would be used in the building of the temple. The

inscriptions all make it clear that Hatchepsut alone was to be regarded as the temple's founder:

18

She made it as a monument to her father Amen on the occasion of stretching the cord over

Djeser Djeseru

, [the ritual laying out of the temple ground-plan] may she live forever, like Re!

Hatchepsut intended her new temple to house both her own mortuary chapel and, on a slightly smaller scale, that of her father, Tuthmosis I. The mortuary chapel in its most simple form, as provided for a private individual, was the place where the living could go to make the offerings of food, drink and incense which would sustain the Ka or soul of the deceased in the Afterlife. The cult-statue, a representation of the dead person which stood within the chapel, became the focus for these daily offerings as it was understood that the soul could actually take up residence within the statue. A royal mortuary chapel, however, was not simply a cafeteria for the deceased. The divine king, once dead, could become associated with a number of important deities, particularly Osiris and Re, both of whom represented a potential Afterlife; the king could choose whether to spend eternity sailing daily across the sky in the solar boat with Re, or relaxing in the Field of Reeds with Osiris. The royal mortuary chapels reflected these associations, providing a dark and gloomy shrine for the worship of Osiris and a light open-air court for the worship of Re. During the New Kingdom they also reflected the growing power of Amen. Amen now started to play a prominent role in the scenes which decorate the walls, and his shrine now formed the focus of the mortuary chapel.

All these elements were to be found at

Djeser-Djeseru

, which was designed as a multi-functional temple with a complex of shrines devoted to the worship of various deities. In addition to the mortuary temples of Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis I, there were twin chapels dedicated to the local goddess Hathor and to Anubis, smaller shrines consecrated to the memory of Hatchepsut's ancestors, and even a solar temple, its roof open to the cloudless Theban sky, dedicated to the worship of the sun god Re-Harakte. The main shrine was, however, devoted to the cult of Amen Holiest of the Holy, a variant of Amen with whom Hatchepsut would become one after death. It was as the focus of the Amen-based ‘Feast of the Valley’, an annual festival of death

and renewal, that

Djeser-Djeseru

played an important part in Theban religious life.

The Feast of the Valley was celebrated at new moon during the second month of

Shemu

or summer. Amen normally dwelt in splendid isolation in the sanctuary of his own great temple at the heart of the Karnak complex. Here he spent the days and nights in his dark and lonely shrine, visited only by the priests responsible for performing the rituals of washing and dressing the cult-statue, and by those who tempted him daily with copious offerings of meat, bread, wine and beer. However, on the appointed day he would abandon the gloom of his torchlit home and, accompanied by the statues of Mut and Khonsu, would cross the river to spend the night with Hathor at

Djeser-Djeseru

.

With an escort of priests, musicians, incense-bearers, dancers and acrobats and doubtless an excited crowd of Thebans, and with his own golden barque carried high on the shoulders of his servants, Amen made his way in the bright sunlight along the processional avenue to the canal. Here he embarked on his barge, sailed in state across the Nile and navigated his way through the network of canals which linked the mortuary temples of the West Bank. He disembarked at the small Valley Temple situated on the desert edge (now entirely destroyed) and, after the performance of a religious rite, proceeded along the gently sloping causeway which, aligned exactly on Karnak, was lined with pairs of painted sphinxes. Along the route there was a small barque shrine where his bearers could pause if necessary before passing into the precincts of the temple proper. That same evening many Theban families would set off in procession for the West Bank where they too were to spend the night, not in a temple, but in the private tomb-chapels of their relations and ancestors. The hours of darkness were spent drinking and feasting by torchlight as the living celebrated their reunion with the dead. After the climax of the Feast, a religious rite performed at sunrise, Amen sailed back to his temple, and the bleary-eyed townsfolk returned home to bed.

The

Djeser-Djeseru

was surrounded by a thick limestone enclosure wall. Once through the gate, Amen passed immediately into a peaceful, pleasantly shaded garden area where T-shaped pools glinted in the sunlight and trees – almost certainly the famous fragrant trees

from Punt – offered a tempting respite from the fierce desert sun. Looking upwards, Amen would have seen the temple in all its glory; a softly gleaming white limestone building occupying three ascending terraces set back against the cliff, its tiered porticoes linked by a long, open-air stairway rising through the centre of the temple towards the sanctuary. Amen's route lay upwards. Passing over the lower portico he reached the flat second terrace where his path was marked out by pairs of colossal, painted red-granite sphinxes, each with Hatchepsut's head, inscribed to ‘The King of Upper and Lower Egypt Maatkare, Beloved of Amen who is in the midst of

Djeser-Djeseru

, and given life forever’.

The second imposing stairway continued upwards so that Amen entered the body of the temple on its upper and most important level. Amen passed from the bright desert light to the cool shade and, making his way between the imposing pairs of kneeling colossal statues which lined the path to the sanctuary, he reached his journey's end; the haven of his own dark shrine cut deep into the living rock of the Theban mountain. Here the secret, sacred rites would be performed by torchlight, and magnificent offerings would first be presented to the god and then shared out between his priests.

It is possible that Hathor too only spent a limited amount of time at

Djeser-Djeseru

. A much-damaged scene on the northern wall of the outermost room of the shrine depicts the arrival of the barque of Amen at the Valley temple. Hathor's barque is also shown, as indeed are three empty royal barges which seem to belong to the two kings Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis III and to their ‘queen’, the Princess Neferure. These three have presumably left their boats to join the festivities. The accompanying text suggests Hathor's visitor status:

Shouting by the crews of the royal boats, the youths of Thebes, the fair lads of the army of the entire land, of praises in greeting this god, Amen, Lord of Karnak, in his procession of the ‘Head of the Year’… at the time of causing this great goddess [Hathor] to proceed to rest in her temple in

Djeser-Djeseru

-Amen so that they [Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis III] might achieve life forever.

19

Hathor, ‘Lady of the Sycamores’, ‘Mistress of Music’ and patron of love, motherhood, and drunkenness, could take several forms. She could appear as the nurturing cow-goddess who suckled amongst others the