Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (28 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Hatchepsut had started her regal building programme early, anticipating her elevation to the throne by ordering a pair of obelisks from the Aswan granite quarry while still queen regent. By the time these had been cut she was an acknowledged king, and her newly acquired royal titles could be engraved on their tips. Obelisks – New Kingdom cult objects intended to be a stone representation of the first beams of light to illuminate the world – were tall, thin, square stone shafts tapering to a pyramid-shaped peak. Traditionally erected in pairs before the entrance to the temple, their twin tips were sheathed in gold foil so that they sparkled and shimmered in the rays of the fierce Egyptian sun. Obelisks were dedicated to the god by the king, and their shafts contained columns of hieroglyphs giving details of their erection and dedication. However, they were also regarded as living beings; obelisks were given personal names, and offerings were made to them.

In continuing the newly established obelisk tradition, Hatchepsut was once again emulating the deeds of her esteemed father who, with the help of Ineni, had been the first monarch to erect a pair of obelisks before the entrance to the Karnak temple. Indeed, Hatchepsut tells us how Tuthmosis himself had urged his daughter to follow his precedent: ‘It is your father, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Aakheperkare [Tuthmosis I], who gave you the instruction to raise obelisks.’

6

To Senenmut fell the responsibility of overseeing operations and, in an inscription carved at the Aswan granite quarry, we see him standing to present his work to his mistress who is still only a ‘King's Great Wife’:

… the Hereditary Prince, Count, great favourite of the God's Wife… the Treasurer of the King of Lower Egypt, Chief Steward of the Princess Neferure, may she live, Senenmut, in order to inspect the work on the two great obelisks of Heh. It happened just as it was commanded that everything be done; it happened because of the power of Her Majesty.

7

The successful planning, cutting, transportation and erection of a pair of obelisks was a remarkable feat of engineering for a society totally reliant

on man-power, river transport and human ingenuity. Some successful New Kingdom examples reached over 30 m (98 ft) in height and weighed over 450 tons (457,221 kg) while Hatchepsut's ‘unfinished obelisk’, abandoned in the Aswan quarry after it developed a fatal crack, would have stood over 41 m (134 ft) tall and weighed an estimated 1,000 tons (1,016,046 kg).

8

The work in the granite quarry was physically demanding, labour intensive and mind-numbingly repetitive. After a suitable band of rock had been identified, a series of small fires was lit and doused with water to crack the surface of the granite which could then be worked with relative ease. Once the uppermost face had been prepared the sides were cut not by saw – the granite was far too hard – but by teams of men rhythmically bouncing balls of dolerite (an even harder rock) against the granite surface. The underside was then prepared in the same way until the obelisk was lying supported by isolated spurs of the mother-rock and a large quantity of packing stones. The supporting spurs were then knocked away, the packing carefully removed, and the obelisk was ready to be dragged to the canal where it would be loaded on a barge and towed first to the River Nile and thence to Thebes. The classical historian Pliny, fascinated by the techniques developed to load the unwieldy obelisks on the barges during the Roman Period, noted how:

A canal was dug from the river Nile to the spot where the obelisk lay and two broad vessels, loaded with blocks of similar stone a foot square – the cargo of each amounting to double the size and consequently double the weight of the obelisks – was put beneath it. The extremities of the obelisk remaining supported by the opposite sides of the canal. The blocks of stone were removed and the vessels, being thus gradually lightened, received their burden.

9

Hatchepsut included Senenmut's work amongst the major achievements of her reign, recording the transportation of the obelisks both in a series of illustrations on blocks from the Chapelle Rouge at Karnak and on the lower southern portico of her Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple. Here we are shown the two obelisks lying lashed to sledges as they are towed on a sycamore wood barge towards Thebes by a fleet of twenty-seven smaller boats powered by over 850 straining oarsmen. Fortunately, the flow of the river helps the barge on its way. The

transport of the obelisks is an important civil and religious event, and the great barge is accompanied by three escort ships whose priests appear to be blessing the proceedings. The two obelisks are not shown as we might expect, lying side by side, but are lying base-to-base, their tips pointing up and down stream respectively. To transport the obelisks in this way would have required an enormously long barge (over 61 m, or 200 ft), and the difficulties in handling such a long vessel would have been daunting even for the Egyptians, who were accomplished boatmen. It seems highly likely that this artistic convention intended to stress the fact that there were actually two obelisks rather than one, and that the obelisks were in fact transported side by side. Upon their arrival in Thebes there is a public celebration. A bull is killed, and further offerings are made to the gods. Of course, it is Hatchepsut, not Senenmut, who takes full credit for the achievement, and on the displaced blocks of the Chapelle Rouge we see the new king presenting the obelisks to her father Amen. The bases of these two obelisks may still be seen at the eastern end of the Amen temple at Karnak; their shafts have long been destroyed.

Hatchepsut's second pair of granite obelisks was commissioned to mark her

sed

-jubilee in Year 15. This time the granite came from the island of Sehel at Aswan, and the work was under the control of the steward Amenhotep:

The real confidant of the King, his beloved, the director of the works on the two big obelisks, the chief priest of Khnum, Satis and Anukis, Amenhotep.

10

The new obelisks were erected in the hypostyle hall of Tuthmosis I – its roof and pillars being removed for the occasion – and here one still stands. It is now, at 29.5 m (96 ft 9 in) high, the tallest standing obelisk in Egypt. The inscriptions carved on the shaft and base once again follow the same old themes, stressing Hatchepsut's relationship with both her earthly and her heavenly father and emphasizing her right to rule, but we are also provided with some original details concerning the commissioning of the monument:

My majesty commissioned the work on it in Year 15, day 1 of the 2nd month of winter, ending in Year 16, the last day of the 4th month of summer, making seven months from the commissioning in the quarry. I did this for him [Amen] with affection as a king does for a god. It was my wish to make it for him, gilded with electrum… My mouth is effective in what it speaks; I do not go back on what I have said. I gave the finest electrum for it, which I measured in gallons like sacks of grain. My Majesty called up this quantity beyond which the Two Lands had ever seen. The ignorant know this as well as the wise.

11

While Hatchepsut's first pair of obelisks was entirely covered in gold foil, ‘two great obelisks, their height 108 cubits, wrought in their entirety with gold, filling the two lands [with] their rays’,

12

the second pair had gold leaf applied only to their upper parts.

The erection of the obelisks was perhaps the most spectacular of the improvements which Hatchepsut made to

Ipet-Issut

, or ‘The Most Select of Places’, now better known as the Karnak temple complex. The Karnak temple had retained its same basic 12th Dynasty form throughout both the Second Intermediate Period and the reigns of Kamose and Ahmose. However, during the time of Amenhotep I, when the war of liberation was completed and the sandstone and limestone quarries had been re-opened, serious building works commenced. From this reign onwards, each succeeding New Kingdom king attempted to outdo his predecessors in the scale of his or her embellishments, and the temple slowly grew from a relatively simple collection of mud-brick chapels and shrines linked by processional ways to become the vast religious complex whose magnificent ruins may be seen today.

Although the Great Temple of Amen remained the focus of the site, and the Theban Triad (Amen, Mut and Khonsu) were always its principal gods, a variety of other deities was worshipped at Karnak and there were eventually chapels dedicated to Montu, Ptah, Sekhmet, Osiris, Opet and Maat. There was a substantial temple dedicated to Amen's spouse, Mut, which stood within its own enclosure wall and which was linked to the Great Temple by a paved processional way, and a much smaller temple of their moon-god son Khonsu situated close to that of his father, Amen. The Karnak temple was connected to the nearby temple of Amen-Min at Luxor by a processional way lined by sphinxes, and was linked to the River Nile by a system of canals.

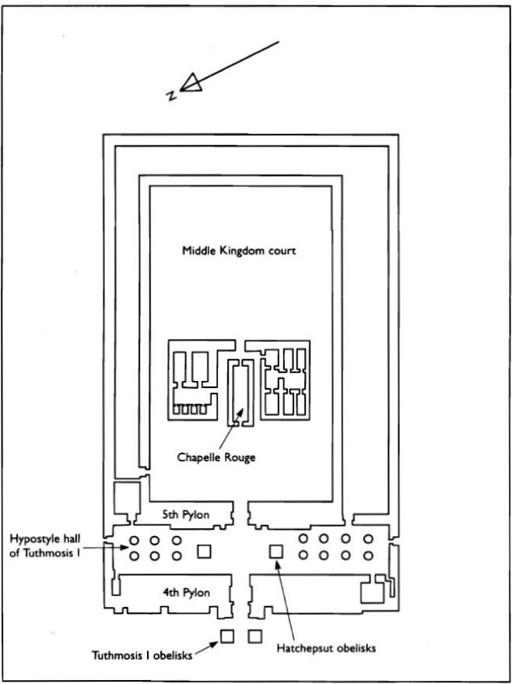

Fig. 6.2 Reconstruction of the Amen temple at Karnak during the reign of Hatchepsut

Within the grounds of the temple complex was a small mud-brick palace which, lacking any sleeping quarters, was used during the celebration of some of the religious rituals associated with kingship, par-ticularly the coronation. We know that during Hatchepsut's reign this palace was situated on the north side of the temple façade, but unfortunately no trace of it now remains. The larger, fully equipped palace where the King and her retinue stayed while visiting Thebes is also lost; almost certainly built on lower ground (the Karnak temple was on the raised mound of the old township), this palace is probably now below the level of the ground water.

Amenhotep I had started the Karnak embellishment ball rolling by adding an alabaster kiosk or barque shrine, a monumental gateway, a limestone replica of the White Chapel of Senwosret I and a cluster of smaller shrines or chapels. Tuthmosis I made far more extensive improvements; in addition to his famous pair of obelisks, he built two white stone pylons or gateways (pylons IV and V) which were connected by the hypostyle entrance hall where Hatchepsut later placed her obelisks, and he extended the processional ways. Even the short-lived Tuthmosis II undertook some improvements to the temple, although a few re-used blocks are now all that remain of his efforts.

Hatchepsut's main contribution to the Temple of Amen was her Chapelle Rouge, the red quartzite barque sanctuary of Amen which has already been discussed in some detail in

Chapter 4

. The Chapelle stood on a raised platform immediately in front of the original mud-brick and limestone Middle Kingdom temple, flanked to the north and south by groups of smaller sandstone cult shrines, the so-called ‘Hatchepsut Suite’ whose decorations show the king making offerings before a variety of gods. At the same time improvements were made to the processional way which linked the temple of Amen to the temple of his consort Mut, and a series of wayside kiosks was built to provide resting places for the barque of Amen as it travelled from temple to temple within the Karnak complex. A new pylon (pylon VIII), a magnificent monumental gateway passing between two tall towers each topped by a gold-tipped flagpole, was the first such gateway to be built on the southern axis of the temple. This pylon was originally decorated with images of Hatchepsut as king, but suffered at the hands of later ‘restorers’, so that Tuthmosis III and Seti I are now shown on the reliefs and Tuthmosis III and Tuthmosis II (who replaces Hatchepsut) appear on the doorway.

The tourists who annually swarm into Thebes seldom depart from the ancient city of Amen without visiting the magnificent natural amphitheatre of Deir el-Bahri, where the hills of the Libyan range present their most imposing aspect. Leaving the plain by a narrow gorge, whose walls of naked rock are honeycombed with tombs, the traveller emerges into a wide open space bounded at its furthest end by a semi-circular wall of cliffs. These cliffs of white limestone, which time and sun have coloured rosy yellow, form an absolutely vertical barrier. They are accessible only from the north by a steep and difficult path leading to the summit of the ridge that divides Deir el-Bahri from the wild and desolate Valley of the Tombs of the Kings. Built against these cliffs, and even as it were rooted into their sides by subterranean chambers, is the temple of which Mariette said that ‘it is an exception and an accident in the architectural life of Egypt’.

13

Hatchepsut's mortuary temple,

Djeser-Djeseru

or ‘Holiest of the Holy’, was set in a natural bay in the Theban cliffs on the West Bank of the Nile close to the ruined mortuary temple of the 11th Dynasty King Mentuhotep II and almost directly opposite the Karnak temple complex. Later Tuthmosis III was to choose a nearby site for his own West Bank temple dedicated to Amen,

Djeser-Akhet

or ‘Holy Horizon’. The name Deir el-Bahri, which literally means ‘Monastery of the North’, and which is now often used to refer both to the general area and more specifically to Hatchepsut's mortuary temple, is a reference to the mud-brick Coptic monastery established at the site during the fifth century

AD

.