Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (30 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

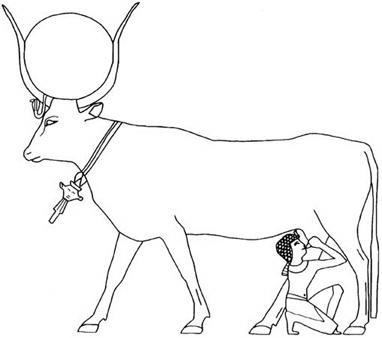

Fig. 6.4 Hatchepsut being suckled by the goddess Hathor in the form of a cow

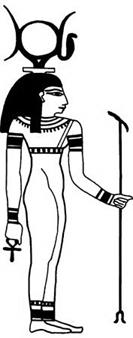

infant Hatchepsut, as the serpent goddess, the ‘living uraeus of Re’ who symbolized Egyptian kingship, as a beautiful young woman or as a bloodthirsty lion-headed avenger. She could even, in her more sinister role as the ‘Seven Hathors’, become a goddess of death. Hatchepsut seems to have felt a particular devotion for Hathor, a devotion which may well have stemmed from her period as queen-consort. Throughout the dynastic period successive queens of Egypt were each closely identified with Hathor, and indeed during the Old Kingdom several queens had left the seclusion of the harem to serve as priestesses in her temple. This tradition had faded somewhat during the Middle Kingdom, but the strong queens of the late 17th and early 18 th Dynasties had revived it, becoming firmly associated with the goddess in her dual role as divine consort and mother of a king. Our best-known example of a queen associated with Hathor comes from the smaller temple at Abu Simbel, Southern Egypt, whose colossal statues of Queen Nefertari,

wife of Ramesses II, show her represented as the goddess. Contemporary depictions of Hathor show her wearing the customary queen's regalia so that the link between the queen and the goddess is made obvious to all.

Hatchepsut dedicated a number of shrines to Hathor in her various manifestations; these often took the form of a rock-cut sanctuary fronted by a colonnade or vestibule. The Speos Artemidos with its unfinished Hathor-headed pillars may be included amongst these, as Pakhet was a local version of Hathor's fierce lion-headed form. It is therefore not too surprising that Hatchepsut's mortuary temple, established on the site of a traditional shrine and home to a chapel dedicated to Hathor, includes many representations of this goddess. Here she is not only shown as a cow feeding the baby Hatchepsut, she plays an important role during Hatchepsut's birth and she even, in her role as ‘Mistress of Punt’, manages to gain a mention in the tale of Hatchepsut's epic mission. This link between Hatchepsut and a powerful, female-orientated mother-goddess is highly significant, suggesting as it does that Hatchepsut principally known for her association with the male god Amen may not have been averse to having her name linked with a predominantly feminine cult.

20

Fig. 6.5 Hathor in her anthropoid form

Almost all New Kingdom cult temples were decorated with scenes intended to demonstrate the good relationship which existed between the king and his gods. The outer, more public parts of the temples (the pylon and courtyard) usually depicted the pharaoh in his most obvious

role, that of the warrior-king defending his land against the traditional enemies of Egypt, while the inner, more private areas showed more intimate scenes: here the king could be seen acting as high priest, or making an offering before the cult statue.

Djeser-Djeseru

cannot be classed as a typical New Kingdom temple. Not only did the building have an unprecedented three-tiered design, its owner also had her own unique propaganda message which she was determined to put across via the walls of her temple. Nevertheless, and bearing these two important differences in mind, the scenes found on the two lower porticoes do seem to contain the same mixture of public and more private scenes that we might expect to find at a more conventional temple site.

21

The two broad stairways connecting the terraces effectively cut the temple in two, so that the two lower porticoes which front the temple are divided into four distinct sections. Here we find scenes depicting significant events from Hatchepsut's life and reign, all chosen to emphasize her filial devotion to Amen. Along the bottom south (or left hand as we face the temple) portico we see scenes of the refurbishment of the Great Temple of Amen at Karnak, including the erection of the famous obelisks, while on the opposite side of the same portico, which is now unfortunately much destroyed, we are shown Hatchepsut in her role as the traditional 18th Dynasty huntin’, shootin' and fishin' pharaoh; she takes the form of an awesome sphinx to trample the enemies of Egypt, and appears as a king fowling and fishing in the marshes. The middle portico tells the tale of Hatchepsut's divine birth and coronation (northern side) and the story of the expedition to Punt (southern side). At each end of this portico is a chapel, the northern chapel being dedicated to Anubis, the jackal-headed god of embalming, and the southern chapel, possibly the site of her original Deir el-Bahri shrine, being dedicated to Hathor.

The uppermost level, the most important part of the temple, took the form of a hypostyle hall fronted by an Osiride portico with each of its twenty-four square-cut pillars faced by an imposing, twice life-sized, painted limestone Osiriform statue of Hatchepsut staring impassively outwards over the Nile Valley towards Karnak. These statues were matched by the ten Osiride statues which stood in the niches at the rear of the upper court, by the four Osiride statues in the corners of the sanctuary and by the enormous Osiride statues – each nearly 8 m (26 ft) tall – which stood at each end of the lower and middle porticoes. All

these statues showed the king with a white mummiform body and crossed arms holding the emblems of Osiris, the ankh or life sign and the

was

-sceptre, symbol of dominion, combined with the traditional emblems of kingship, the crook and flail. Her bearded face was painted either red or pink, her eyes were white and black and her eyebrows a rather unnatural blue, while on her head Osiris/Hatchepsut wore either the White crown of Upper Egypt or the double crown.

On the southern side of the upper portico was the mortuary chapel of Hatchepsut, a rectangular vaulted chamber with an enormous false-door stela of red granite occupying almost the entire west wall. The cult-statue of Hatchepsut would have stood directly in front of this stela. Next door was the much smaller chapel allocated to the cult of Tuthmosis I; the west wall of his chamber has been demolished and his false-door stela is now housed in the Louvre Museum, Paris. It is possible that there was originally an even smaller chapel dedicated to the cult of Tuthmosis II, although all trace of this has now been lost. On the opposite side of the upper portico was an open-air solar temple with a raised altar of fine white limestone dedicated to the sun god Re-Harakhte. There was also a small chapel dedicated to Anubis and to Hatchepsut's family; here her parents Tuthmosis I and Ahmose and her non-royal grandmother Senisenb all appear on the walls. The sanctuary itself, two dark, narrow interconnected rooms designed to hold the barque of Amen and the statue which represented the god himself, was carved with images of the celebration of the beautiful Feast of the Valley; Hatchepsut, Neferure, Tuthmosis I, Ahmose and Hatchepsut's dead sister Neferubity all appear on the walls to offer before the barque.

Hatchepsut's mortuary cult was abandoned soon after her death, and

Djeser-Akhet

took over as the site for the celebration of the Feast of the Valley. It is therefore highly likely that Senenu, High Priest of both Amen and Hathor at

Djeser-Djeseru

during Hatchepsut's lifetime, was both the first and last to hold this exalted post. However, the cult of Amen and, to a lesser extent, the cult of Hathor continued to be celebrated at

Djeser-Djeseru

until the end of the 20th Dynasty. By this time the Tuthmosis III temple

Djeser-Akhet

and the Mentuhotep II mortuary temple had been abandoned and both lay in ruins. The Hatchepsut temple, its upper level now badly damaged, continued to flourish as a focus for burials until, during the Ptolemaic period, it became the cult centre for the worship of two deified Egyptians, Imhotep the builder of

the step-pyramid, and the 18th Dynasty sage and architect Amenhotep, son of Hapu. The Amen sanctuary was cleared of its rubble, extended and refurbished for their worship. The site then fell again into disuse until the fifth century

BC

when it was taken over by a Coptic monastery who also used the Amen sanctuary as a focus for their worship. The site was finally abandoned some time during the eighth century

AD

, apparently because rockslides had rendered the upper levels dangerous.

7

Senenmut: Greatest of the Great

I was the greatest of the great in the whole land. I was the guardian of the secrets of the King in all his places; a privy councillor on the Sovereign's right hand, secure in favour and given audience alone… I was one upon whose utterances his Lord relied, with whose advice the Mistress of the Two Lands was satisfied, and the heart of the Divine Consort was completely filled.

1

Amongst Hatchepsut's loyal supporters there is one who stands out with remarkable clarity. Senenmut, Steward of the Estates of Amen, Overseer of all Royal Works and Tutor to the Royal Heiress Neferure, played a major bureaucratic role throughout the first three-quarters of Hatchepsut's reign. As one of the most active and able figures of his time, Senenmut occupied a position of unprecedented power within the royal administration; his was the organizational brain behind Hatchepsut's impressive public building programme, and to him has gone the credit of designing

Djeser-Djeseru

, one of the most original and enduring monuments of the ancient world. And yet, in spite of a comprehensive list of civic duties successfully accomplished, it has almost invariably been Senenmut's private life which has attracted the attention of scholars and public alike. In effect, Senenmut's considerable achievements have not merely been blurred as we might expect by the passage of time, they have been distorted and almost effaced by a host of preconceptions and speculations concerning Senenmut's character, his motivation and even his sex life.

2

The traditional tale of Senenmut, a classic rags-to-riches romance with a moral ending warning the reader against the twin follies of over-ambition and greed, is generally told as follows:

Senenmut, the highly talented and fiercely ambitious son of humble parents, started his career in the army where his natural abilities soon became apparent. Driven by a burning desire to shake off his lowly

origins, he rose rapidly through the ranks before quitting the army to join the palace bureaucracy. Here, once again, his remarkable skills soon became apparent and Senenmut enjoyed accelerated promotion to become a high-grade civil servant. As it became obvious that there was no immediate heir to the throne, the royal court started to buzz with intrigues and plotting. Senenmut now took the calculated decision to link his future totally with that of Hatchepsut. He became the female king's most loyal supporter within the palace as he worked ruthlessly and efficiently to ensure that, against all the odds, her reign would succeed. When his gamble paid off, and Hatchepsut finally secured her crown, Senenmut was amply rewarded for his loyalty. He was showered with a variety of secular and religious titles including the prestigious Stewardship of the Estates of Amen, a position which allowed him free access to the vast wealth of the Karnak temple. His most publicized role was, however, that of tutor to the young princess Neferure.