How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine (29 page)

Read How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine Online

Authors: Trisha Greenhalgh

6.

Guidelines may produce undesirable shifts in the balance of power between different professional groups (e.g. between clinicians and academics or purchasers and providers). Hence, guideline development may be perceived as a political act.

7.

Out-of-date guidelines might hold back the implementation of new research evidence.

But the counter argument to the excessive use, and particularly the compulsive imposition, of clinical guidelines is a powerful one, and it was expressed very eloquently some years ago by Professor J Grimley Evans [8].

There is a fear that in the absence of evidence clearly applicable to the case in the hand a clinician might be forced by guidelines to make use of evidence which is only doubtfully relevant, generated perhaps in a different grouping of patients in another country at some other time and using a similar but not identical treatment. This is evidence-biased medicine; it is to use evidence in the manner of the fabled drunkard who searched under the street lamp for his door key because that is where the light was, even though he had dropped the key somewhere else.

Grimley Evans' fear, which every practising clinician shares but few can articulate, is that politicians and health service managers who have jumped on the evidence-based medicine (EBM) bandwagon will use guidelines to decree the treatment of diseases rather than of patients. They will, it is feared, make judgements about people and their illnesses subservient to published evidence that an intervention is effective ‘on average’. This, and other real and perceived disadvantages of guidelines, are given in Box 10.2, which has been compiled from a number of sources [2–6]. But if you read the above-mentioned distinction between guidelines and protocols, you will probably have realised that a good guideline wouldn't

force

you to abandon common sense or judgement—it would simply flag up a recommended course of action for you to consider.

Nevertheless, even a perfect guideline can make work for the busy clinician. My friend Neal Maskrey recently sent me this quote from an article in the

Lancet

.

We surveyed one [24-hour] acute medical take in our hospital. In a relatively quiet take, we saw 18 patients with a total of 44 diagnoses. The guidelines that the on call physician should have read, remembered and applied correctly for those conditions came to 3679 pages. This number included only NICE [UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence], the Royal Colleges and major societies from the last 3 years. If it takes 2 min to read each page, the physician on call will have to spend 122h reading to keep abreast of the guidelines

[9].

The mushrooming guidelines industry owes its success at least in part to a growing ‘accountability culture’ that is now (many argue) being set in statute in many countries. In the UK National Health Service, all doctors, nurses, pharmacists and other health professions now have a contractual duty to provide clinical care based on best available research evidence. Officially produced or sanctioned guidelines—such as those produced by the UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence

www.nice.org.uk

—are a way of both supporting and policing that laudable goal. Whilst the medicolegal implications of ‘official’ guidelines have rarely been tested in the UK, courts in North America have ruled that guideline developers can be held liable for faulty guidelines. More worryingly, a US court recently refused to accept adherence to an evidence-based guideline (which advised doctors to share the inherent uncertainty associated with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in asymptomatic middle-aged men, and make a shared decision on whether the test was worth doing) as defence by a doctor being sued for missing an early prostate cancer in an unlucky 53-year-old [10].

How can we help ensure that evidence-based guidelines are followed?

Two of the leading international authorities on the thorny topic of implementation of clinical guidelines are Richard Grol and Jeremy Grimshaw. In one early study by Grol's team, the main factors associated with successfully following a guideline or protocol were the practitioners' perception that it was uncontroversial (68% compliance vs 35% if it was perceived to be controversial), evidence-based (71% vs 57% if not), contained explicit recommendations (67% vs 36% if the recommendations were vague) and required no change to existing routines (67% vs 44% if a major change was recommended) [7].

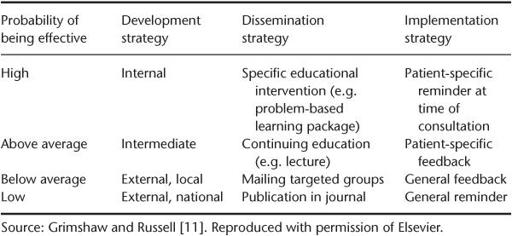

Another early paper, by Grimshaw and Russell [11], summarised in

Table 10.1

, showed that the probability of a guideline being effectively followed depended on three factors:

a.

the development strategy (where and how the guideline was produced);

b.

the dissemination strategy (how it was brought to the attention of clinicians); and

c.

the implementation strategy (how the clinician was prompted and supported to follow the guideline, including organisational issues).

Table 10.1

Classification of clinical guidelines in terms of probability of being effective

In terms of the development strategy, as

Table 10.1

shows, the most effective guidelines are developed locally by the people who are going to use them, introduced as part of a specific educational intervention, and implemented via a patient-specific prompt that appears at the time of the consultation. The importance of ownership (i.e. the feeling by those being asked to play by new rules that they have been involved in drawing up those rules) is surely self-evident. There is also an extensive management theory literature to support the common-sense notion that professionals will oppose changes that they perceive as threatening to their livelihood (i.e. income), self-esteem, sense of competence or autonomy. It stands to reason, therefore, that involving health professionals in setting the standards against which they are going to be judged generally produces greater changes in patient outcomes than occur if they are not involved.

Grimshaw's conclusions from this early paper were initially misinterpreted by some people as implying that there was no place for nationally developed guidelines, because only locally developed ones had any impact. In fact, whilst local adoption and ownership is undoubtedly crucial to the success of a guideline programme, local teams produce more robust guidelines if they draw on the range of national and international resources of evidence-based recommendations and use this as their starting point [12].

Input from local teams is not about reinventing the wheel in terms of summarising the evidence, but to take account of local practicalities when operationalising the guideline [12]. For example, a nationally produced guideline about epilepsy care might recommend an epilepsy specialist nurse in every district. But in one district, the health care teams might have advertised for such a nurse but failed to recruit one. So the ‘local input’ might be about how best to provide what the epilepsy nurse would have provided, in the absence of a person in the post.

In terms of dissemination and implementation of guidelines, Grimshaw's team [13] published a comprehensive systematic review of strategies intended to improve doctors' implementation of guidelines in 2005.

The findings confirmed the general principle that clinicians are not easily influenced, but that efforts to increase guideline use are often effective to some extent. Specifically:

- improvements were shown in the intended direction of the intervention in 86% of comparisons—but the effect was generally small in magnitude;

- simple reminders were the intervention most consistently observed to be effective;

- educational outreach programmes (e.g. visiting doctors in their clinics) only led to modest effects on implementation success—and were very expensive compared to less intensive approaches;

- dissemination of educational materials led to modest but potentially important effects (and of similar magnitude to more intensive interventions);

- multifaceted interventions were not necessarily more effective than single interventions;

- nothing could be concluded from most primary studies about the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Grimshaw et al.'s 2005 review reversed some previous ‘received wisdom’, which was probably the result of publication bias in trials of implementation strategies. Contrary to what I said in the first and second editions of this book, for example, expensive complex interventions aimed at improving the implementation of guidelines by doctors are generally no more effective than simple, cheaper, well-targeted ones. Only 27% of the intervention studies reviewed by Grimshaw's team were considered to be based (either implicitly or explicitly) on an explicit theory of change—in other words, the researchers in such studies generally did not base the design of their intervention on a properly articulated mechanism of action (‘A is intended to lead to B which is intended to lead to C’).

In a separate paper, Grimshaw's team [14] argued strongly that research into implementing guidelines should become more theory-driven. That recommendation inspired a significant stream of research, which has been summarised in a review article by Eccles and team [15] and in a systematic review of theory-driven guideline development strategies by Davies and colleagues [14]. In short, applying behaviour change theories appears to improve uptake of guidelines by clinicians—but is not a guarantee of success, for all the reasons I discuss in Chapter 15 [16].

One of Grimshaw's most important contributions to EBM was to set up a special subgroup of the Cochrane Collaboration to review and summarise emerging research on the use of guidelines and other related issues in improving professional practice. You can find details of the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group on the Cochrane website (

http://www.epoc.cochrane.org/

). The EPOC database now lists thousands of primary studies and over 75 systematic reviews on the general theme of getting research evidence into practice.

Box 10.3 Outline framework for assessing a clinical guideline (see also Appendix 1)

- Objective

: the primary objective of the guideline, including the health problem and the targeted patients, providers and settings - Options

: the clinical practice options considered in formulating the guideline - Outcomes

: significant health and economic outcomes considered in comparing alternative practices - Evidence

: how and when evidence was gathered, selected and synthesised - Values

: disclosure of how values were assigned to potential outcomes of practice options and who participated in the process - Benefits, harms and costs

: the type and magnitude of benefits, harms and costs expected for patients from guideline implementation - Recommendations

: summary of key recommendations - Validation

: report of any external review, comparison with other guidelines or clinical testing of guideline use - Sponsors and stakeholders

: disclosure of the persons who developed, funded or endorsed the guideline

Ten questions to ask about a clinical guideline

Swinglehurst [1] rightly points out that all the song and dance about encouraging clinicians to follow guidelines is only justified if the guideline is worth following in the first place. Sadly, not all of them are. She suggests two aspects of a good guideline—the content (e.g. whether it is based on a comprehensive and rigorous systematic review of the evidence) and the process (how the guideline was put together). I would add a third aspect—the presentation of the guideline (how appealing it is to the busy clinician and how easy it is to follow).

Like all published articles, guidelines would be easier to evaluate on all these counts if they were presented in a standardised format, and an international standard (the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument) for developing, reporting and presenting guidelines was recently published [17]. Box 10.3 offers a pragmatic checklist, based partly on the work of the AGREE group, for structuring your assessment of a clinical guideline; and Box 10.4 reproduces the revised AGREE criteria in full. Because few published guidelines currently follow such a format, you will probably have to scan the full text for answers to the questions given here. In preparing this list

Box 10.4 The six domains of the AGREE II instrument (see reference [16])