It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation (26 page)

Read It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation Online

Authors: M.K. Asante Jr

Consider what Kwame Ture remembers about “concealment of historical truth” when he was a student in the West Indies:

The first one is that the history books tell you that nothing happens until a white man comes along. If you ask any white person who discovered America, they’ll tell you “Christopher Columbus.” And if you ask them who discovered China, they’ll tell you “Marco Polo.” And if you ask them, as I used to be told in the West Indies, I was not discovered until Sir Walter Raleigh needed pitch lake for his ship, and he

came along and found me and said “Whup—I have discovered you,” and my history began

.

We must begin to see why Ture never learned, for instance, the rhyme “In 1493 / Columbus stole all he could see.”

It is this kind of gross “concealment” that historically has led to events like the 1960s Ocean Hill-Brownsville conflict in New York City, where African-American parents and other community members sought local control of the public schools in their neighborhoods. One of their major grievances was that the curriculum then, just like now, was not culturally relevant. This has also sparked a rise in African-centered schools like the Lotus Academy in Philadelphia whose mission is:

To provide an educational opportunity for our children that is founded on the basis of culture that is steeped in African culture, history and tradition. We feel that it is important for our students to be grounded and have a good understanding of who they are. The accomplishments of our ancestors and those who walked before us and all of the subject areas this particular foundation is reinforced, whether we’re teaching math or history, science or social studies, we infuse the African perspective. So Lotus provides an opportunity for students to learn, to think, communicate, and problem solve within a framework of an African perspective

.

Schools like these recognize, as environmentalist Baba Dioum does, that, “In the end, we conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught.” If we want to continue the mighty contributions that we’ve made in art, culture, medicine, and science, it’s essential that we know our history.

“I want to show y’all how to survive in this system,” I told the students.

Some years ago, singer Lauryn Hill, speaking to a small crowd at the MTV studios in Manhattan, said “I had to be a living example… I’ve become one of those mad scientists who does the test on themselves first.” Similarly, “Two Sets of Notes” was something I’d applied at the high school, college, and graduate levels, so I knew it worked.

“As students of color, we have to take initiative with regards to our education, especially in classes like history. It may be presented to you through your history books that history is a fact. No, history is a debate. Napoleon said that ‘history is a lie agreed upon’—

Agreed upon by whom?

you must ask. Question, question, question. Challenge. Hit the library, the Internet, the bookstores, the elders, and find out who Garvey was, who Asantewaa was, who Rodney was. Then, once you find out, ask yourself and your teachers why you weren’t taught about these African giants.” Of course, however, you must pass the test. This kind of double note-taking is reminiscent of freethinking Soviet students who learned one set of facts at home but knew the facts they were required to regurgitate in school.

I explained to them that to take two sets of notes is not easy or fair. It requires reading books, articles, and documents that aren’t assigned in class; watching films that aren’t in movie theaters; and listening to music that’s not on the radio. One must become an active agent in one’s educational process.

“You should not depend upon school exclusively for your education,” I informed them. “Self-education is just as, if not more, important.” School can never be the be-all and end-all. At any level of formal school, self-education is also vital. In many ways, self-education moves against what we’ve been taught “education” is. Consider that self-education implies self-motivation as opposed to grade-motivation

and careerism; it implies a willingness to engage in new activities and experiences as opposed to rote learning and uniformity; it allows one to recognize the teachers and lessons that are omnipresent rather than the hierarchy that assumes the teacher is all-knowing; it suggests acting on what is learned rather than simply memorizing and regurgitating information for quizzes and tests; it also implies the asking and reasking of questions, rather than the suppression of questions.

I reminded the students at King Drew that although self-educating might sound a bit daunting at first, the alternative is far worse.

“And remember what Felix Okoye, founder of the African and Afro-American Studies department at SUNY Brockport, said, ‘It would be better not to know so many things than to know so many things that are not so.’”

Students of color—any color—it is imperative that we take two sets of notes, if we wish to gain a clear and healthy understanding of the world. We must understand that, as James Baldwin told his students, “American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

Before I exited the stage, I left the students with a message from Buddha that I couldn’t agree with more:

Make the effort to obtain information that will allow you to best guide your destiny. Make your voice heard in the world through your life and works and do not be cowered into inaction by status, tradition, race, ethnicity, gender or affiliation. Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in anything simply because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down to many generations. But after observation and analysis, when you find that

anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, then accept it and live up to it

.

As you move through the dense wilderness of formal education, trying, with all of your soul to retain your sanity, remember to always

TAKE TWO SETS OF NOTES!

*

It should be noted that I use the term “Katrina”; however, most of the damage down in New Orleans was caused by the breaching (or blowing up) of the levees after the hurricane, and not by Katrina itself.

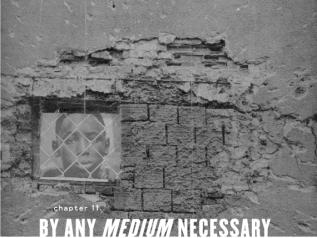

The function of art is to do more than tell it like it is — it’s

to imagine what is possible.—

BELL HOOKS

The scene:

A group of young men, hoodies hovering over their nodding heads, huddle to form a cipher in East Baltimore.

X:

Yo, niggaz in my hood sell crackMove weight, and clap back

I stay strapped…

X:

Yo, yo

, I

know niggaz that kill for nothin’Here, take these cracks and move somethin’

Take this gat, and body somethin’

X: I

walk around with big gunsNiggaz in my crew’ll kill for funds

For fun, fuck bitches and run…

I used “X” not because I don’t know their names, but because by sounding so similar, they misplaced their identities. If I had simply shut my eyes at any given moment during their frenetic flows, their rhymes would have been indistinguishable.

After the cipher, I stuck around to dialogue with the aspiring rappers about their roles as Black artists in America.

“Do y’all consider yourselves artists?” I put out.

“I do,” one of the rappers declared.

“Okay, so as an artist, then, and especially as a Black artist, do you feel that you have a duty to use your art to uplift?” I asked him.

“I mean, I don’t know. The rhymes I spit, that’s reality,

nahmean,”

he shrugged.

“It’s like a mirror, man,” another rapper chimed in. “What you see is what you get.”

“That’s real,” another added, nodding his dome in confirmation.

Just as their rhymes were analog replicas, so were their justifications for spittin’ them. They were echoing not just an ideology that can be found in mainstream rap, but throughout the greater art landscape: film, visual arts, dance, literature.

I shared with them an edict that Paul Robeson once made: “The role of the artist is not simply to show the world as it is, but as it ought to be.” The idea that the filmmakers, rappers, painters, collagists, photographers, choreographers, and other artists of today—amid the arid abundance of desolation and despair—can simply show the ills of the world and then avoid personal responsibility behind the thin veneer of “I’m just a mirror” no longer holds weight.

Yo, anybody can tell you how it is

What we putting down right here is

how it is and how it could be

.—

TALIB KWELI, “AFRICAN DREAM

,”

TRAIN OF THOUGHT

“Yes, the mirror does reflect reality,” I concurred, “but the mirror is no passive instrument. It’s not as uninvolved as ‘what you see is what you get.’ No, the mirror gives us instructions about our appearance and offers us a chance to improve it—that’s what the mirror does.”

“At least a good mirror,” said one of the rappers in the trio as he gave me a pound and repeated, “Improvement.” And as the four of us, on the bitterly cold four-year anniversary of President Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” speech, stood on a battered Baltimore block in a section of the city dubbed “Baghdad,” it became harshly seeable that there was no greater call for improvement than right now.

Here it

is spelled out:

We are at war

.

America, a country that comprises less than 5 percent of the global population, consumes (and wastes) most of the world’s food, resources, and energy. It is a nation fraught with a vulgar material excess that flaunts itself amid sheer poverty and utter desolation. A nation that destroys the most people, animals, plants, habitats, forests, ecosystems, and other

nations

in the pursuit of more…

more everything

. A nation that incarcerates and kills millions of its poor Black and brown citizens. A nation built on and maintained by the burglary of other people’s land and slave labor. A nation of which we are citizens.

How could this be, the land of the free, home of the brave

Indigenous holocaust, and the home of the slaves?—

IMMORTAL TECHNIQUE, “CAUSE OF DEATH

,”

REVOLUTIONARY VOLUME

2

America is a nation of contradictions. Freedom, on one hand, and slavery on the other. Consider that these words—“All men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”—were written, signed, and agreed upon by men who

captured, bought, sold, and tortured my ancestors. Today America launches attacks on nations, killing hundreds of thousands of innocent people in the name of “freedom and liberation.” As Indian novelist and activist Arundhati Roy writes, “free speech,” “free market,” and the “free world” in America have little to do with actual freedom. On the contrary, these terms grant America:

The freedom to murder, annihilate, and dominate other people. The freedom to finance and sponsor despots and dictators across the world. The freedom to train, arm, and shelter terrorists. The freedom to topple democratically elected governments. The freedom to amass and use weapons of mass destruction—chemical, biological, and nuclear. The freedom to go to war against any country whose government it disagrees with. And, most terrible of all, the freedom to commit these crimes against humanity in the name of “justice,” in the name of “righteousness,” in the name of “freedom.”

In an atmosphere rife with grotesque, state-sponsored contradictions, the fundamental question arises: Who will contradict the state?

[enter the artivist]

Who will stage a colorful resistance against the oppression and domination our government imposes on its Black and brown citizens? On the world? Who will promote self, sisterly, and brotherly love? Who will demand justice? Who will be the voice for the voiceless? Who will not only speak, but dance, paint, film, and sing truth to power? Who will contradict war and death? If not us

—artivists—

than who?