Jessen & Richter (Eds.) (71 page)

Read Jessen & Richter (Eds.) Online

Authors: Voting for Hitler,Stalin; Elections Under 20th Century Dictatorships (2011)

“ G E R M A N Y T O T A L L Y N A T I O N A L S O C I A L I S T ”

269

areas a hard albeit gradually diminishing core of voters voting “no”

(Omland 2006a, 154–56; Jung 1998, 86).29

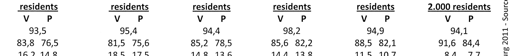

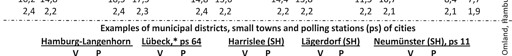

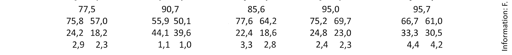

Figure 5: Plebiscite August 19, 1934 (Source: Frank Omland, Hamburg 2011)

Sören Thomsen has provided a model that enables us to measure the scale

of vote-shifting, which also can be applied to the elections in Schleswig-

Holstein for 1933 and 1934. (Thomsen 1987; Hänisch 2008, 31; Omland

2006a, 73–85).30According to these figures, between 80 and 90 per cent of

those who voted against the National Socialists were former supporters of

the two banned workers’ parties, the KPD and the SPD. This is confirmed

when we evaluate the patterns of voting according to occupation: in

predominantly agrarian areas, support for the National Socialists was at its

highest, while in areas where the sectors of “industry and manufacturing”,

or “service and trade”, were predominant, the support was at its lowest.

The greatest rejection of the National Socialists came from the

workers

,

——————

29 For the results in Germany, see the maps at www.akens.org/akens/texte/diverses-

/wahldaten/index.html (accessed on January 2, 2011).

30 Schleswig-Holstein: 104

Gemeinde

as well as rural areas with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants.

I am indebted to Dr. Dirk Hänisch, Bonn, who calculated the shifts in voting.

270

F R A N K O M L A N D

both employed and unemployed, who in the rural areas in 1933 constituted

almost the only notable opposition to the Nazis. They were responsible for

69 and 97 per cent of all the “no” votes respectively, and were usually

followed by the (unemployed)

white-collar workers

.

These results indicate that the former Communist and Social Democ-

ratic voters in particular used the opportunity to express their dissent. The

majority of opposition votes and abstentions in Schleswig-Holstein came

from supporters of the KPD and, to a much lesser extent, from those of

the SPD, as well as from the Danish minority in certain regions. To do so,

they used every opportunity available to them: they boycotted the ballot,

voted “no”, or spoilt the ballot paper.

The Electorate’s Room for Maneuver

Those who chose to vote “no” took a great personal risk. The peril that

the secrecy of the ballot would be broken was real, as an example from the

district of Stormarn demonstrates. Here, in 1936, two members of an elec-

tion committee marked ballot papers, which prompted the local authorities

to ask the NSDAP for a response:

According to

Kreisleiter

Friedrich, the KPD is particularly active in Billstedt and Oststeinbek. This will be the reason why the two men accused committed the act.

They wanted to establish the identity of those likely to be hostile to the state. They did this, though, in a most unfortunate manner. [F.O.: This sentence is crossed out in the report]. Both undoubtedly meant well, however.31

Those voting “no” were taking a political and public stance against the

Nazi regime. The election results at polling-station and local level, as well

as the written sources for Schleswig-Holstein and its surrounding areas,

give an impression of the preconditions for this kind of “dissident use” of

non-choice elections: the electorate could best express their rejection of

the Nazi regime on polling day in those areas where the apparatus of in-

timidation composed of the

Gestapo

and police was relatively weak, where the NSDAP had to struggle against a strong tradition of communist or

social democratic voting, and where there was a relatively strong illegal

——————

31 Stormarn district archives, B 130 (office of community supervision and elections)

Reichstag

elections 1936-1938 file.

“ G E R M A N Y T O T A L L Y N A T I O N A L S O C I A L I S T ”

271

resistance movement (Omland 2006a, 55–7). Established ideologies, social

networks and an environment of opposition all encouraged, then, a poten-

tial “no” vote.

In Schleswig-Holstein, the electorate’s room for maneuver was still

large enough in 1933 and 1934 to allow dissenting voters to express their

disapproval in every ballot. They had to be prepared, though, for possible

consequences: there was still the threat that non-voters would be identi-

fied, that the secrecy of the ballot would be broken, and that deviant be-

havior would be punished. Therefore, to vote “no”, to post an invalid bal-

lot paper, or to abstain from voting at all, required great personal courage.

Although it was only a small minority who expressed their dissent towards

the Nazi regime, the

Volksgemeinschaft

that the National Socialists sought to establish could not be achieved in the face of such deviant behavior. According to Nazi ideology, Germany was “totally National Socialist” and

every

Volksgenosse

had allegedly voted voluntarily for the regime. It was to achieve their aim of having no votes against them that the regime sought in

1936 and 1938 to conceal any deviation from a hundred per cent result.

The election campaign organized by Goebbels, the social control exercised

by the Party, and the vote-rigging instituted in 1936 by the

Reichsinnen-

ministerium

, all contributed to the desired outcome of almost hundred per cent voting for the regime.

Conclusion

The Nazi dictatorship claimed to be a superior alternative to parliamentary

democracy. An article published in 1934 in the Kiel Party newspaper, be-

gan with the question, “Hitler—democrat or dictator?” The author first

distinguished Hitler from the Italian dictator Mussolini, then denounced

“French-Jewish” parliamentary democracy, and finally claimed:

Only Germany has a real democracy [...] The fact that we do not have a dictator-

ship in Germany is down to the

Führer

Adolf Hitler [...] And again the

Führer

proves himself to be a man of the people, as someone who wants to make sure

that the state and the way that it is led are in accordance with the

Volk

as a whole.