Living in Threes (2 page)

Authors: Judith Tarr

Tags: #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Teen & Young Adult, #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Coming of Age, #Aliens, #Time Travel

I’ve always told myself stories. I started writing them down as soon as I knew how. When I got my first computer that was all my own, I’d found the place where I could always go.

I wasn’t always safe there. Stories aren’t about being safe. On the screen, where the words were, I was home—more than I was anywhere except in the barn or in my own house.

A year ago, when the cancer came in, it was scary, but then there was the remission and I told myself that was it, we’d go on and nothing would change. Mom wouldn’t get sick again.

But the world was different. I couldn’t trust it any more.

The only world I could trust was the one I made for myself. The only light was on the screen, pale like moonlight, black like the sky between the stars. Outside it was a steaming hot Florida afternoon, with the sun beating down and the thunderheads piling up. In here, it was as cold as the truth I’d had to face, the day Mom came home from the doctor and sat me down and told me she was going to die.

Today wasn’t anything like that. She was just dumping me for the summer—same as Dad used to do, till he stopped even bothering to show up. Just like Dad, she thought it was great. Romance! Adventure! All the things she’d never had time to do, so I got to do them instead.

I closed my eyes and made myself go away. Skip over. Ignore. Forget. Be somewhere else. Be someone else—someone as different as it was possible to be.

This wasn’t really a new story. Pieces of it had been in me for as long as I could remember, fragments of words, images, half-remembered dreams, but now it was all there: solid, whole, and so real I could taste it.

Really, I could. It was bitter and salty, like a mouthful of ocean, or too many tears. When I opened my eyes, I was somewhere completely different.

I was inside the story. Instead of me telling it, it was telling me.

Chapter 2

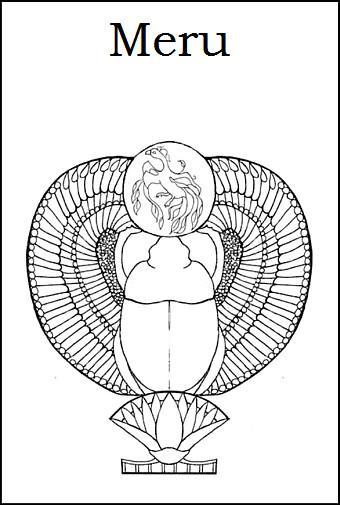

In all Meru’s world, she was sure of two things: that she was born to be a starpilot, and that wherever her mother was, however far she wandered, she would always come home.

The message came over Earth’s web one bitter-bright night, when the air outside the house was so cold it numbed the back of Meru’s throat. She was the room she loved best in this world, high up in the family’s house. Its ceiling was a force field, and by night it was transparent. When she slept there, she lay under the stars.

She had been sharing a webcircle with other star dreamers—Earthlings who dreamed of becoming starpilots. She and Yoshi, who had passed the tests and would be shipping out together to the starpilots’ school, were basking in a cloud of joy and awe and envy.

It felt wonderful, and rather terrifying.

“This is how it will be for the rest of our lives,” Yoshi said to her on an underchannel. “I don’t know if I like it.”

“We’ll be ordinary enough at school,” Meru said, “especially at the start, when everybody knows more than we do.”

“Ai,” said Yoshi. “You are right. I’m not sure I like that, either.”

“It’s worth it,” she said.

His agreement hummed through the weblink.

The link broke abruptly. The message feed was corrupted, the words in it broken and blurred, but the priority tag was still on it, with the finder beacon that told Meru who had sent it.

Meru linked to the beacon and followed it, braced for a long search down the starways—and came to an abrupt and earthbound halt.

That should not have happened. She ran the search more times than she wanted to count, but the answer was always the same. Her mother, who should have been on the other side of the galactic sector, was on Earth, and close by. Something other than distance had garbled the message.

It could be an error, or a ghost in the web. Implants wore out. They could malfunction. There was no need to panic.

Yet.

“Meru? You there?”

The webcircle was still up, and still celebrating. Yoshi’s ping was like a hot wire across bare skin.

“I’m here,” she said.

“But what? What happened?”

“I can’t talk. I can’t stop. I have to go.”

“Meru—”

She shut him off.

Her family gathered below, in the common room where everyone came together in the evenings, or curled in a warm and communal pile in one of the sleeping rooms. Meru missed the warmth suddenly, and the presence of all her cousins and the youngest aunts and uncles.

But two words in the stream had come through without static or garble.

Alone

.

And

Danger.

Meru’s mother was on Earth when she should have been exploring a distant system, and something was wrong.

The web offered no answers. Meru took a deep breath and made herself be calm. She searched for a new message, or even a slightly older one that might have told her more, but there was nothing about a woman of Earth named Jian, daughter and aunt of the family Banh-Liu, mother of Meru.

All Meru found was a babble of newsfeeds off the starweb. They were connected by a single key word:

Epidemic

.

There were always waves of disease on other worlds, plagues that came and went, infected aliens and unprotected humans, then ran their course and disappeared. They never reached Earth; the Consensus that governed it had such strong protections, and such effective quarantine and containment, that there had not been so much as a sniffle on the planet in a thousand years. Earth was the safest place there was, and Consensus had every intention of keeping it that way.

Jian must have been investigating a plague on one of the worlds she explored. Civilizations often rose and fell because of such things, and Jian would want to know everything: who and how and why, and whether the disease was still on the planet, waiting to break out again. It did not in any way explain why she was on Earth and sending such a weak and broken signal.

She could not be sick. If she were, Earth’s protections would never have let her through.

That was not as reassuring as Meru would have liked it to be.

Over against the wall, a shadow stirred. Wings unfurled, half mist, half solid. Eyes glittered above a drift of fog that might have been a beak. The starwing stroked its half-substantial wingtip across Meru’s cheek, a touch like ice and smoke, but strangely warm inside.

It always knew when she was sad or troubled—always had known, since her mother brought back the egg from one of her expeditions, and it hatched in Meru’s hands. No one else she knew had a starwing. It was like a piece of the stars, to remind her of where she was going, and to keep her company when she went there.

She closed her eyes and let its presence soothe her. But not too much. She needed the sting of urgency.

She started down the lift to the common room, to the family and community and consensus. She would tell them what had come to her, and they would tell her what to do.

Alone,

the message had said.

Danger.

Starpilots on voyage did not have community or consensus. They were alone with the ship and the stars. When danger threatened, they faced it—alone.

Meru sent the lift down the back way, away from the family.

She should have known it would not be that easy. No one was in the storage, but her cousin Ulani was in the kitchen, sitting under a lone, dazzling-bright light, finishing off the last of the pickled fish.

“You hate pickled fish,” Meru said.

“I’m teaching myself to like it,” Ulani said. She took a last bite, grimacing only slightly, and swallowed with an air almost of triumph.

“Ah,” said Meru. “Because Aracele likes it.”

Ulani’s eyes dropped. Her feet shuffled. “I’m teaching her to like steamed buns. She says they taste like glue.”

“They do,” Meru said. “It really must be love, if you’re both trying that hard to meet in the middle.”

“She makes me warm inside,” Ulani said. She looked as if she might have said more, but nothing came out.

Meru hugged her suddenly. “Go to bed. Dream about your sea-girl.”

“Aren’t you coming?” Ulani asked.

“In a while,” Meru said.

She had to work hard to keep her voice from shaking. Ulani hesitated, as if she sensed something. Meru held her breath.

Ulani yawned. “Yes, I

am

tired. Don’t you stay up too long, either.”

“I’ll try not to,” Meru said.

Ulani was still yawning as she left the kitchen. Meru waited, listening hard. The whole family could decide to come down, and she would never get away at all.

The house was quiet. One or two of the aunts were on the house network, working through the night. Everyone else was either asleep or nearly there.

Meru gathered a few small things in a bag: a handful of protein bars, a bubble of water, one of the backups for her web implant. Her heart was beating, and she kept forgetting how to breathe.

Foolish,

she said to herself.

In a pair of tendays you’ll be going out alone into space, away from Earth, for a long time and maybe forever. This is only a little thing. A quick search. It’s not even off the continent, let alone off the planet.

When she scolded herself like that, she sounded like Grandmother Ramotswe. She could almost see the long finger shaking, and the dark eyes glaring the silliness out of her.

“I’ll be back as soon as I find Jian,” she said as if her grandmother had actually been there. “That is a promise.” And she meant to keep it.

She left a ping on the data stream, a guide to where she had gone. The family would wake up to it in the morning. By that time or very soon after, Meru hoped, she would have found her mother, and be on her way back home.

She took a deep breath and stepped out of the house, into the breathtaking rush of the wind, and the roar of the sea.

The body suit she wore was a barely visible shimmer, but it was strong enough to protect her against the void of space. Earth’s icy night was nothing to it. Meru allowed the air to penetrate to her face, gasping at the bite of it.

It was fierce, but it cleared her mind. She had been thinking of little past

Mother—urgent—wrongness—go.

Now she had a plan of sorts, and a trail to follow.

Hints and clues on the web led her from the house on its headland above the icy sea, down the empty road in the wind and the drifting snow. The starwing flew above her, shielding her with its wings. When she searched the web to find this road on this island, she saw no sign of herself, not even the flicker of a shadow.

The road down from the house was sand and stone, but it flowed into a smooth river of silver that looked somewhat like water and somewhat like ice. Meru paused before she stepped onto it. Once she set foot on that road, there would be no turning back.

She nearly did. A sleepy ripple on the web, a half-in-a-dream ping from her cousin Ti-shan, echoing and re-echoing through the streams of half a dozen other cousins and aunts and uncles, pulled at her with almost physical force.

Meru? What are you doing? You’re not on the star-roads yet. Come down and share dreams with us.

She wrenched away. Her mother needed her. She had to go.

She braced for the current that would seize her and carry her off the island. It caught her with startling gentleness and wrapped her in a bubble of warm air. Between one sharp-drawn breath and the next, she was skimming toward the dark bulk and distant brightness of the mainland.