Living in Threes (6 page)

Authors: Judith Tarr

Tags: #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Teen & Young Adult, #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Coming of Age, #Aliens, #Time Travel

“Not much,” Dr. Kay answered. “Keep on riding and exercising her, and don’t change her feed for now. We’ll check her again in a month, make sure everything’s where it belongs. Then it’s hurry up and wait.”

“345 days, give or take,” I said. “Only 330 to go.”

“Give or take,” said Dr. Kay. She gave Bonnie one last pat and me one last smile, and packed up and drove off to her next appointment.

Lunch was also our weekly Skype with Aunt Jessie—live from beautiful Luxor, as she liked to put it. The only reason I even did it was because Mom trapped me.

Mom showed up at the barn just before I was about to take off with Cat and Kristen. I couldn’t very well not show her the rest of the ultrasound pictures, or refuse to let her love on Bonnie and tell her what a wonderful, amazing, miraculous horse she was.

Then Mom said handed me the car keys and said, “You’re driving home.”

Bribery works. Cat grinned at me. “See you tonight,” she said.

“Turtle time,” I agreed.

Mom didn’t gloat. That wasn’t how she operated. She kissed Bonnie’s nose and fed her the last carrot in the bag.

I had the car started and the A/C blasting by the time she tore herself away from Bonnie. “When I grow up,” I said, “I’m moving to Iceland.”

“Not Antarctica?”

“No horses.”

“Point,” she said, strapping herself in.

I drove carefully, minding my driver’s education manual. I swear the road got rougher every time I went down it.

Mom was quiet. Dozing, I noticed. She did a lot of that these days.

I thought about slowing down even more, but my back teeth were already rattling out of my head. Mom only flinched at the worst of the bumps. By the time we reached the blissful smoothness of the paved road, she was sound asleep.

I’d exhausted my worry quota months ago. I told myself she was doing this to wear me down till I gave in about Egypt. I really couldn’t go now, could I? Dr. Kay was coming back in a month. Somebody had to be there for that.

We had lunch with Aunt Jessie—virtually. It was dinnertime over there. We put my laptop at her usual place at the table and ate our ham and cheese while she ate her chicken and veg.

I didn’t have much to say. Mom was all full of Bonnie and the ultrasound and the baby.

Finally she stopped pushing it and picked at her sandwich, which she’d eaten a whole quarter of. Aunt Jessie in Luxor was mopping the bottom of her bowl with a chunk of bread.

I peeled my dessert orange piece by piece.

“All right,” Aunt Jessie said to me. “So that didn’t go well, did it? Still hate surprises?”

“Hate,” I said to the pile of orange peel. “Not coming. I’m sorry.”

“No, you’re not sorry,” she said, “and yes, you’re coming. Check your email. There’s a shopping list. You’re good on shots—while you’re getting your hate on, hate Dr. Meldrum, he gave you one or two last month that weren’t on the school list for fall.”

That didn’t surprise me at all. “Is that even legal?”

“Minor child,” Aunt Jessie said with complete lack of remorse. “Parental discretion. It’s for your own good. Once you get here, you’ll love it. Or I’ll be working you so hard you won’t have time to hate it.”

“What if I just won’t get on the plane? I’ll show up with a gallon of hair gel and a riding whip. Raise a stink in the naked scanner.”

“Get arrested. End up on a terrorist watch list. Get hauled off to juvie. Is that what you still call it?” Aunt Jessie grinned. Even through the blurry, jerky screen I could see how much fun she was having. “As long as you’re going to spend your summer in durance vile, you might as well spend it here. The food is better and the doors unlock from the inside.”

“You’d better hope I don’t spend my time learning ancient Egyptian curses. I’ll put one on you.”

“I’ll curse you back,” she said cheerfully. “And I’ve had ’way more practice. See you next Friday. I’ll meet you at the airport.”

She shut the call down from her end. I stared at the empty screen. My own face reflected back at me. I put a mental caption on it.

POWERLESSNESS: It’s What’s for Lunch.

“It’s just for six weeks,” Mom said. “You’ll still have a month to spend with your friends before school starts.”

“But not with Bonnie.”

“Bonnie will be perfectly fine. I’ll check in on her. You know your friends will.

You

can check in on her from online. She’ll be the most checked-in-on horse on the eastern seaboard.”

She was being reasonable. I didn’t want to be reasonable. I wanted to pitch a roaring fit.

A year ago I might have done it. Too bad I had to grow up enough to have some impulse control.

I cleared the table instead, and tossed the leftovers in the disposal and the dishes in the dishwasher.

“We’ll go shopping tomorrow,” said Mom.

“Do I get to pick my own prison uniform?”

“As long as it’s on the list.”

“Pith helmet? Sword cane?”

“Possibly even goggles,” she said, “and a white silk scarf.”

That was our old joke. When I was little, we were going to fly around the world in a biplane, and spy on Dad wherever he happened to be that week.

“Dad’s not in Egypt,” I said. “Is he?”

“Not that I know of.” Mom stood up and stretched. “I have a little work to do still. Then we’ll go out for dinner. Celebrate Bonnie’s baby.”

I opened my mouth to say no thanks, I wasn’t celebrating anything today. Damn impulse control. What came out was, “Fine. Whatever.”

Mom kissed me the way she did when I was six, a flying swoop on the forehead, and went off to do her judge thing. I had the house to myself and an afternoon to kill, and a few people to contemplate killing.

So I did what any self-respecting writer type does. I holed up with my laptop and killed off a bunch of characters. Bloodily. With lots of screaming.

Chapter 6

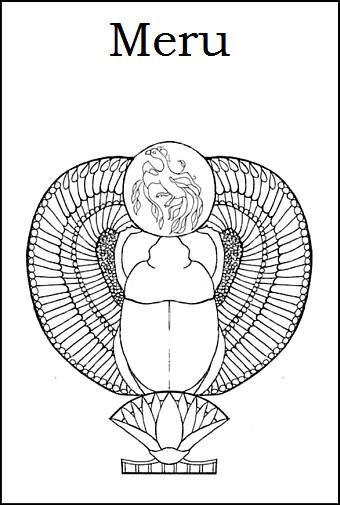

The gaps in the force field were closing. The oldest sector of the old city was almost out of reach. Meru fought her way through crowds so thick they seemed to have been put there deliberately to stop her.

That was impossible. The web was the same as ever, no mention of anything in the old city, though Meru ran search after search while she struggled to get to the oldest sector before the field walled it off completely.

Up above them all, the starwing circled slowly, invisible against the darkness and the starlight. As Meru’s desperation mounted, it began to feed on the field.

This time it fed slowly. It skimmed the edges of the surging energy, drawing off just enough to slow the field’s advance.

Meru reached the wall just ahead of the hum and flicker of the field—a handful of nanoseconds before it closed. She dived through the broken gate, tripped and fell and lay winded in a street as empty as the one outside had been full of people.

There had to be people here. The web said there were, and the starwing could see and feel them, sparks of warmth inside the cold walls of brick and steel and stone.

There was no one in the street. The air smelled strange. Meru had never been sick or known anyone who had, but some deep part of her knew what this was. Blood, vomit, and worse: bodies breaking down, voiding and bleeding and dying.

These were the sparks that the starwing had passed to Meru through the web, with an undertone of jangling wrongness. For every living thing it found, there were a hundred that had been living once. The walls around her, the houses that lined the street, were full of the dead.

The web refused to acknowledge them. When she searched with those parameters, it said,

Not found

, or else gave her yet another news report about a plague on a planet a hundred light-years away. There was no plague on Earth. The web said so.

But it was here. She could smell it. She

knew

.

Meru began to run.

Anyone sensible would have run away. Meru ran toward the place where Jian had been. Her thoughts were empty of anything but the need to be there, to see. To know. And then—

Then nothing. She could not think past it at all.

The place she ran to was near the heart of the sector. There, finally, were people: men and women sealed into space armor that sent off the signal of Consensus.

The starwing passed through the force field with no more than a shiver and a tingle as the energy fed its strange substance, and wrapped its wings around Meru. Inside that insubstantial shield, the starwing told her deep inside her mind, far below the oblivious hum of the web, she was invisible even to Consensus’ sensors.

That was a disturbing thought, but the message that had brought Meru here was much worse. She slipped through the cordon of the Guard. The door to the tall grey house was open, and for a priceless few instants, no one guarded it.

It was dim inside. A lightstrip ran up the stair, shedding just enough pale green glow to guide Meru’s feet. The landings along the way were deserted, the hallways dark. They smelled of the sickness, and of something heavier and sweeter.

That, she realized, was the smell of death. Her stomach heaved; she stumbled. There was a word in her head now, a simple word, the only word in this nightmare world:

No.

The starwing’s purr steadied her. She pulled herself upright. One more flight. One more landing. One last corridor, and a battered and broken door hanging half off its track.

The man who stood inside was not Jian, but Meru knew him as well as she knew her mother. He was her uncle, after all.

He saw her, which she had not expected. “Meru! What are you doing here?”

“Vekaa,” she said, still stupid from the shock of what she had seen and smelled and sensed. “What—”

He moved to block the doorway. “Go now,” he said. “Just go.”

Meru would dearly have loved to do that. More than anything, she did not want to know what was in that room. But she had come all this way. Jian had called her. She had to know.

The starwing brushed Vekaa with the edge of a wing. He snapped back as if he had been struck with an energy bolt.

Meru wasted no time staring. She slipped past Vekaa, and stopped.

Jian was dead. Her face was empty. So was the web where she had been. The message was gone, the last synapse fired, the mind and consciousness dissolved.