Miss Chopsticks (31 page)

Authors: Xinran

I met the girl whom I have called âSix' in Beijing in 2002. She too came from a poor area in the north of Anhui Province and was actually the ninth child in a family of ten. She had a healthy younger brother, but four of her elder sisters had died young. When I asked her how, she said âof natural causes', but it was hard to be sure whether she was being truthful. In the remote, poverty-stricken areas of China girls are of no more value than donkeys, horses, cattle or goats.

I had gone into a small teahouse to find out what had happened to a good vegetarian restaurant I remembered in the area. âSix' was wearing a uniform in the traditional style, and had a piece of paper in front of her on which she was writing in English. She told me that lots of people came into the teahouse to ask questions about places they had known but could no longer find. She had heard her boss say that the vegetarian restaurant had been pulled down. Out of curiosity, I asked which university she was at, and praised her for using the quiet moments in the teahouse to study. When she replied that she had never been to university, and that actually she was a migrant worker who liked books and wanted to save money to go and study abroad, I was flabbergasted. I had talked to many young female migrant workers, but a âchopstick' girl with such a deep love of books and the desire to study abroad was rarer than a phoenix or a unicorn. I was extremely eager to interview her, and to ask her more about herself.

I made a date with âSix' to visit the bookshops in the Wangfujing shopping street with me on her free half-day.

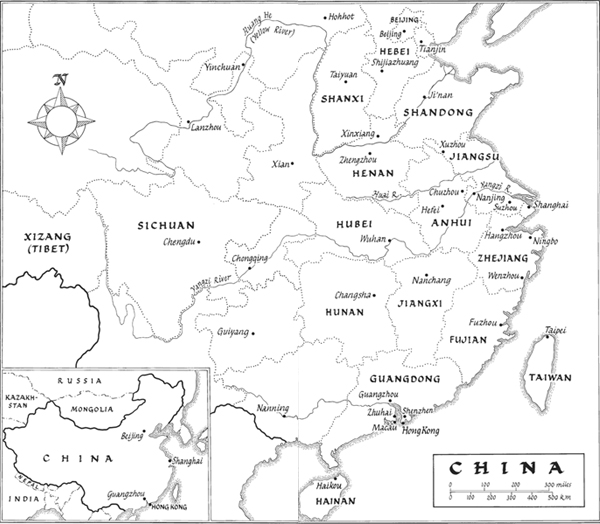

There I bought for her tapes and books that would help her prepare for the English exams she needed to take, and afterwards we went to a traditional Beijing restaurant for supper. Hoping to imprint on this young girl's heart good memories of her native land before she went abroad, I ordered dishes with a strong regional flavour: sliced cold beef with hot, pungent spices from Sichuan called Husband-and-Wife Lung Slices; Manchurian pickled vegetables; deep-fried silver whitebait from the Yangzi delta; and a bowl of Cantonese âDragon and Tiger Fighting' (wanton and noodles). We talked as we ate, and by the time our plates were empty, I had written down her story.

In 2003 I went back to the teashop, full of excitement at the prospect of seeing her again. I had brought with me information packs from British universities. But both she and the teahouse had vanished. The neighbours said that that teahouse had been shut down for âselling banned books'. I was not able to find the girl again. All I had was a telephone number for the teahouse which simply gave a ânumber unobtainable' tone.

They say that âout of blows, friendship grows', and that is how I got to know âFive'.

In 2003, my English husband and I met an American man in Shanghai who was amazed at having discovered that a Chinese businessman he was dealing with held his meetings in a bathhouse. I wasn't quite so amazed. Ancient texts like the

Medical Canon of the Yellow Emperor

show how the nurturing of the body has been central to Chinese culture for centuries. But, while the American man's discovery made me feel patriotic, it simply made my husband curious. I could see the gleam in his eye: he was eager to visit one of Shanghai's âWater-Culture Centres' to experience for himself this revived interest in the medicinal properties of water.

It was late afternoon when we arrived at the baths. We collected our tokens and towels from reception, and were given various health checks before separating to take a shower. It is important to be clean before entering medicinal pools. But when I got into one of the pale-blue shower cubicles and bolted the door, disaster struck. I turned on the cold tap only to find that the water was scalding hot. Thinking that perhaps the taps had been wrongly labelled, I tried the hot tap, only to find that hot water came out of that one too. I immediately tried to turn off the taps but the threads were so worn that they wouldn't turn. The shower head was set at such an angle that the water (which was getting hotter and hotter) sprayed in front of the door, making it impossible for me to unlock the cubicle without burning myself further. All I could do was squeeze myself into the corner furthest away from the jet of water, and call for help.

After a while an attendant heard my cries, but explained, extremely slowly, that she had no way to open the door from the outside. I would have to open it myself. On hearing this, I became frantic.

âIf you don't find a way to get me out of here, I'm going to be seriously injured,' I said. âI can't keep my body away from the water entirely, and it's scalding me. Hurry and find someone who can turn it off.'

âReally?' The voice outside still seemed not to sense the urgency of the situation.

âListen to me!' I shouted, âIf you don't hurry up and find someone, you'll be blamed for my injuries!'

When I think back on it, my voice must have sounded terrifying. I heard the girl running away. While I waited, I tried to keep changing position so that different parts of my body took the pain. I had counted up to two hundred by the time I heard rushing footsteps and shouting:

âWhich cubicle? Good heavens, didn't they seal that one off last night? How come it's open again? That's the one that doesn't work properly! Quickly, go and turn off the hot water! The other customers will just have to be cold for a moment. If there's trouble, I'll take responsibility. Now get a move on. Turn off the stopcock!'

There was another burst of running footsteps, and then the hot water stopped. I opened the door to find three women in uniforms standing open-mouthed outside the cubicle, staring at my bright red body.

âSorry, we're sorry,' they apologised in chorus.

âI'm afraid that, although my brain understands you, my body doesn't,' I said resentfully.

At this, the youngest of the three women stepped forward and began to take charge in a very capable manner. Signalling to her colleagues that they should go and turn the hot water back on, she said that she would look after me. I recognised her voice: she was the one who had promised to take responsibility if any of the other customers complained about the cold water.

âMy name's Mei,' she said. âI'm going to take you to the Skin Treatment Room where they can look at your burns.' Without giving me a chance to object, she gently placed a big bath towel around my shoulders and led me to a treatment room. The towel was extremely painful wherever it came into contact with my skin, but the doctor in the treatment room promised that the salve he was using would get rid of the redness and pain in half an hour.

He was right: the pain did begin to ease, especially when Mei gave me a foot massage afterwards. While she was rubbing my feet we talked, and I found out that she too came from Anhui. By the time my husband and I left the Water-Culture Centre late that night, Mei and I had become firm friends. She is the âFive' in this book, and really was her parents' fifth child.

Because Mei couldn't read, we were only able to keep in touch by telephone, which we did for nearly two years. Then, in September 2005, I was told by another employee of the Water-Culture Centre that Mei had been sent on a course of advanced study, and that she did not have her new telephone number.

I was perplexed. How could a girl who couldn't read or write be sent on a course of âadvanced study'? But then I thought again: through sheer hard work, Chinese people have achieved many things that others have thought impossible.

I wrote this Afterword during a visit to Tasmania, where I was staying in a small wooden hut next to Cradle Mountain. February is the height of summer there, and there were days when the sun was so strong it could burn your skin. On other days, however, there would be snow flying outside my window. In Cradle Mountain, they call it the Sky Mother looking for her children who went out during the summer to play.

On the last night I spent in Tasmania, I was taken with a group of other people to see a colony of Little Penguins. It was a rainy, windy night and we walked through the dark down to the sea, chatting to each other in our excitement. When we got there, our guide told us to be quiet. âPlease don't use flashlights, and be careful where you put your feet. You are now in the penguins' territory.' As he spoke, he switched on a special torch, designed to give off a gentle light. Its beam revealed a huge crowd of tiny penguins standing right in front of us â not black and white, like the ones I had learned about in school, but dark-blue and white. The largest was barely twenty centimetres high, and they were all waving their tiny, soft wings, and calling out to each other as they searched for their mates. My companions and I were awed by the peaceful harmony in which these little creatures lived.

Involuntarily I greeted them in Chinese. Who knows â I might have been the first person ever to speak Chinese to them. The guide asked us three questions: âWhy are the penguins waddling so awkwardly? Why do they make so light of having to spend five or six hours climbing from the sea to the top of the ridge? And why are they making so much noise?

A long silence followed. We could hear nothing but the ocean and the penguins âdiscussing' our ignorance.

Since no one in the group knew the answers to the questions, our guide provided them. As I listened to him, surrounded by the roar of the ocean and the cries of the penguins, my heart wept.

âFirstly, penguins can't bend their legs. Think how difficult it would be to climb a mountain with no knees! What would take us ten minutes to climb, takes them hours, with many rest-stops. Why do they do it every day? Because their mates and babies are at the top of the ridge, and they must bring them food. And finally, the noise ⦠The ocean is the place that gives them life and keeps enemies at bay; on dry land they and their offspring are far more exposed to predators. So when love drives them to climb the ridge for their family, they are worried, confused and lonely. They need the calls of their own kind to comfort them â¦'

The guide's words seem a fitting footnote to the story of Three, Five and Six, and all the peasant women who come to work in China's cities, or labour in the fields from dawn to dusk. They do not have the advantages we were born with â the knees that allow us to walk freely through our lives and our choices. Many of them have never been cuddled by their parents, never touched a book, never had warm clothes, never eaten their fill. But in conditions that we would consider âimpossible', they fight for their self-respect, their aspirations, their loves.

Just as I was humbled by the sight of the little

Tasmanian penguins who had struggled up the ridge, I am full of admiration for the chopstick girls who, with their energy, give us so much.

Thank you.

There are many different festivals celebrated in the cities and villages of China, and the way in which they are marked varies from region to region. It is impossible to list them all, but here are the some of the most important ones:

Spring Festival

,

also known as Chinese New Year

(last day of 12th lunar month and the first 5â15 days of 1st lunar month): This is the most important festival in the Chinese year. First preparation is made for New Year. Houses are cleaned, the family banquet is prepared and people paste pictures of the âdoor gods' onto their front doors to protect the family. Relatives visit each other and there are fireworks.

Lantern Festival

(15th day of 1st lunar month): Celebrated with the lighting of lanterns and lion dances.

Tomb Sweeping Day

,

also known as the Festival of Pure Brightness

(12th day of 3rd lunar month): A day for honouring one's ancestors by cleaning their tomb and burning ceremonial paper money. Families go on outings.

Dragon Boat Festival

(5th day of 5th lunar month): This

festival commemorates the death of the great Chinese poet Qu Yuan, who committed suicide by drowning. Dragon boat races are held. People also eat Zong Zi, glutinous rice dumplings wrapped in bamboo leaves. It is also a time when people protect themselves against illness. It is thought that this period of the year is when the Five Poisonous Creatures (snakes, scorpions, spiders, lizards, toads) awake from hibernation and cause harm, particularly to small children. Parents protect their children by giving them special clothes to wear decorated with pictures of the Five Poisonous Creatures.