Omelette and a Glass of Wine (31 page)

Read Omelette and a Glass of Wine Online

Authors: Elizabeth David

Tags: #Cookbooks; Food & Wine, #Cooking Education & Reference, #Essays, #Regional & International, #European, #History, #Military, #Gastronomy, #Meals

2.

Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine

, Alexandre Dumas, 1873.

3.

Les 366 Menus de Baron Brisse

, 2nd edition 1875, first published

c.

1867.

The last years of Queen Victoria’s reign and the beginning of the Edwardian era saw the rise to fame and prosperity of the great London hotels we know to-day; the Savoy, the Ritz, the Carlton, the Berkeley, Claridges (even then known as ‘the home of kings’), the Piccadilly, the Hyde Park and – the only one which has since disappeared – the Cecil. At that time Romano’s was at the height of its glory; Mr Lyons and Mr Salmon were presiding at the Trocadero; and at Simpson’s in the Strand a fish luncheon for three, consisting of turbot, stewed eels, whitebait, celery and cheese, with two bottles of Liebfraumilch, cost

£

1. 1s. 3d.

The restaurant world of that period was described in detail by the Edwardian gourmet, Colonel Newnham-Davis, the gastronomic correspondent of the Pall Mall Gazette. The Colonel made a habit of inviting to dinner certain of his friends whom, in his subsequent reports, he would disguise under discreet pseudonyms. A regular guest of his was Miss Dainty, an actress. One evening she dined with him at, curiously it seems to us, the Midland Hotel. A railway hotel dinner in those days seems hardly to have been the dread experience

it would be to-day. The Colonel and Miss Dainty ate oysters, soup, sole, a fillet of beef cooked with truffles and accompanied by

pommes de terre soufflées

, wild duck

à la presse

, a pudding and an ice-cream (

bombe Midland

). With a bottle of wine this meal cost 28s. for the two of them.

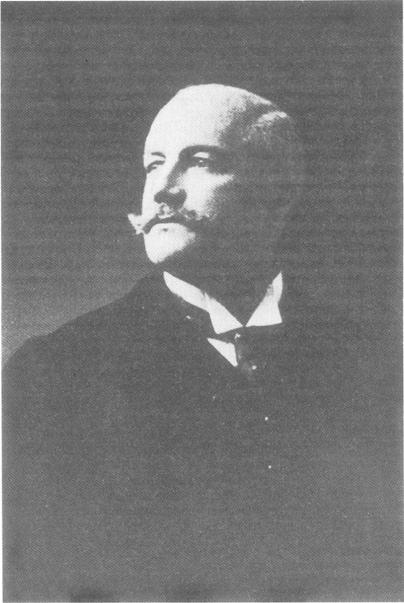

Colonel Newnham-Davis. Photograph front

Le Carnet d’Epicure Janvier 1914

and restored by Hawkley Studio Associates Ltd

Miss Brighteyes was a debutante who, to her host’s grief, drank lemonade with her caviare and gossiped of dresses and weddings while she ate

terrine de foie gras.

The Colleen – what a tiring girl she sounds – prattled incessantly of horses. The little Prima Donna was an American taken by the Colonel to the Star and Garter at Richmond. They had a pleasant drive down there (Goodwood was over and London deserted) and arrived at sunset; on this occasion the food was not a great success. There was

petite marmite

and, not for the first time, the Colonel is at a loss to understand why some restaurant managers seem unaware of the existence of any other soup. The mullet was not fresh – ‘I guess it has not been scientifically embalmed,’ said the Prima Donna.

I should like to think that the Colonel’s sister-in-law (the daughter of a dean) to whom he gave dinner at the Café Royal, the Aunt whom he entertained at the Walsingham, and the Uncle whom he nicknamed the Nabob, were really his relations and not figments of his humorous imagination. Alas, they are just a trifle over life size.

The dean’s daughter did not care for shell-fish, so they were forced to start dinner with caviare. The inevitable clear soup followed (

pot au feu

this time); the sole was served in a delicate sauce almost imperceptibly flavoured with cheese, and the dean’s daughter appreciated it so much that the Colonel’s initial peevishness began to wear off. The lamb which followed the sole was tough. Foie gras came next, then quails

en cocotte.

The ice which ended the meal was christened

Pôle Nord

and consisted of a soft cream encased in ice-cream, resting on an ice pedestal carved in the shape of a bird sitting on a rock. This creation cost 2s. 6d., the foie gras 4s. Champagne Rosé was what they drank and, with liqueurs and coffee, the total bill came to

£

2.4s.6d.

The maiden aunt who was invited to Walsingham House arrived in a four-wheeler. She wore a stiff black silk dress, a lace cap and an expression of disapproval – ‘I hope they won’t take me for one of your actress friends,’ she boomed. The Walsingham was in Piccadilly, on the site now occupied by the Ritz; from the Colonel’s description of the panelling of inlaid woods, the white pillars and cornices touched with gold, the curtains of deep crimson velvet, the

ceiling of little cupids floating in roseate clouds, the dining-room must have been every bit as ravishing as the pink and white Louis XVI restaurant which succeeded it and which, under the direction of César Ritz, became synonymous with all that was elegant, rich and glamorous in the early years of this century.

Mrs Tota and her husband George were friends from the Colonel’s Indian Army days. George, it has to be faced, was a bore; he grunted and grumbled and refused to take his wife out to dinner on the grounds that the night air would bring on his fever. So the Colonel gallantly invited Mrs Tota, a maddeningly vivacious young woman, to a select little dinner for two. She was homesick for the gaieties of Simla, the dainty dinners and masked balls of that remarkable hill station. ‘We’ll have a regular Simla evening,’ declared the Colonel, and for this nostalgic excursion he chose to dine in a private room at Kettner’s, which still exists to-day, in Romilly Street, Soho; after dinner they were to proceed to a box at the Palace Theatre, return to Kettner’s, where they arranged to leave their dominos, and thence to a masked ball at Covent Garden. The meal, for a change, began with caviare, continued with

consommé, filets de sole à la Joinville, langue de bœuf aux champignons

accompanied by spinach and

pommes Anna

(how agreeable it would be to find these delicious potatoes on an English restaurant menu to-day), followed by chicken and salad, asparagus with

sauce mousseline

, and the inevitable

ice.

They drank a bottle of champagne (15s. seems to have been the standard charge at that period, 1s. each for liqueurs). Mrs Tota was duly coy about the private room decorated with a gold, brown and green paper, oil paintings of Italian scenery and gilt candelabra (‘Very snug’, pronounced the Colonel); she enjoyed her dinner, chattered nineteen to the dozen and decided that Room A at Kettner’s was almost as glamorous as the dear old Châlet at Simla.

Although he was strictly fair in his reports and seldom expressed a particular preference, it is clear that one of the Colonel’s favourite restaurants was the Savoy. It was D’Oyly Carte, of Gilbert and Sullivan fame, who invited César Ritz, then at the Grand Hotel, Monte Carlo, to come to London and take charge of his recently opened Savoy Hotel. With him Ritz brought Escoffier to supervise the kitchens, and Echenard, proprietor of the famous Hôtel du Louvre, Marseille, to assist him as manager in the restaurant – a formidable combination indeed; no wonder the Savoy soon became the favourite haunt of stage celebrities, industrial magnates, Indian

princes (there was a well-known curry cook attached to the Savoy kitchens) and, in fact, of all classes of the rich, the great, the greedy. Escoffier’s

mousse de jambon

, served on a great block of ice and melting like snow in the mouth, was recognised as a masterpiece; and the

bortsch

, with cream stirred into the hot strong liquid, was declared by Colonel Newnham-Davis to be the best soup in the world.

Joseph, who succeeded the Ritz-Escoffier partnership, had an almost unique devotion to his art. On one occasion, when Sarah Bernhardt was the guest of honour at a Savoy dinner, he cooked the greater part of the meal at a side table under her very eyes; his carving of the duck was a flamboyant display of swordsmanship; when asked if he ever went to the theatre he replied that he would rather see six gourmets eating a perfectly cooked meal than watch the finest performance of Bernhardt or of Coquelin.

A few years later, the Savoy became the scene of all manner of fabulous banquets. At one of these the courtyard was flooded to represent a Venetian canal, tables were arranged all round, and Caruso sang to the guests as he floated in a gondola.

What, I wonder, would our reactions be to-day to these junketings? What of the long menus and, the everlasting sameness of the food? With stupefaction one thinks of the wholesale slaughter of ducks and chickens, of pheasant and quail, the shiploads of Dover sole and the immense cargoes of foie gras from France, of caviare from Russia, the crates of champagne and the tons of truffles, which went to make up a single day’s entertainment in the great hotels of Europe. By present day standards the prices were, of course, absurd, although the cooking was luxurious and the service impeccable.

The

petite marmite

, the

pot au feu

, the

croûte au pot

were made with rich beef, veal and chicken stock; the fillets of sole were invariably cooked with truffles and cream or with mushrooms and lobster sauce, with artichoke hearts or with white wine and grapes;

noisettes d’agneau

, from the finest baby lamb, made such frequent appearances on the menu that one wonders how any sheep has survived; the chicken was stuffed with a

mousse de foie gras;

the little birds which followed – quail, ortolan or snipe – were again presented with truffles; asparagus, in and out of season, were always accompanied by hollandaise sauce; and the

bombe glacée

, indispensable, it seems, to a good dinner, was the signal for all the display of which the confectionery chef was capable.

The wines were probably better than anything we shall ever drink

again in England, and served in the proper manner. What on earth would the Colonel have said to the waiter at a world famous hotel, who the other day brought a bottle of Chambertin to the table in a bucket of ice? What, for that matter, would he have done, when confronted with the pile of chips and mass of Brussels sprouts heaped onto a plate containing an alleged

sole meunière

, in a restaurant where they ought to know better?

Even so, a course of Edwardian dinners might well prove a sore trial to-day. Although Colonel Newnham-Davis consistently pleaded for more varied menus and shorter meals, this did not prevent him from ordering and eating, with evident enjoyment and approval, what seems to-day a perfectly astounding meal. On this occasion, his uncle, the peppery old Nabob, was bidden to dine at the Cecil Hotel, in order that it might be proved to him that a respectable curry could be had outside the portals of the East India Club. This is the menu as recorded by the Colonel and solemnly consumed down to the last

friandise

:

Hors-d’œuvre variés

Consommé Sarah Bernhardt

Filet de sole à la garbure

Côtes en chevreuil: Sauce poivrade

Haricots verts à la Villars

Pommes Cecil

Mousse de foie gras et Jambon au champagne

Curry à l’indienne

Bombay duck, etc., etc.

Asperges

Bombes à la Cecil

Petites friandises choisies

By the time they reached the curry, which was accompanied by a whole battery of poppadoms, chutneys and relishes, it was hardly surprising that the Nabob’s resistance had almost given out. He was only able to murmur, ‘Good, decidedly. I don’t say as good as we get it at the Club’ – there was still a spark of spirit left in him – ‘but decidedly good.’ It should be added that the dinner, with champagne, liqueurs and cigarettes, cost

£

2.8s.6d., and that the

bombe à la Cecil

appeared with an electrically illuminated ice windmill as a background.

Go

, 1952

‘I’ll Be with You in the Squeezing of a Lemon’

Oliver Goldsmith

In 1533 the Company of Leathersellers offered Henry the Eighth and Anne Boleyn a great banquet to celebrate Anne’s coronation on Whit Sunday in Westminster Hall. Among the princely luxuries which graced the feast was one lemon, one only, for which the Leathersellers had paid six silver pennies.

Now that in England we pay an average of six copper pence per lemon, I think I would still find them almost worth the silver pennies which in 1533 must have represented a pretty large sum.

It is hard to envisage any cooking without lemons, and indeed those of us who remember the shortage or total absence of lemons during the war years, recall the lack as one of the very worst of the minor deprivations of those days.

Without a lemon to squeeze on to fried or grilled fish, no lemon juice to sharpen the flatness of the dried pulses – the red lentils, the split peas – which in those days loomed so largely in our daily diet, no lemon juice to help out the stringy ewe-mutton and the ancient boiling fowls of the time, no lemon juice for pancakes, no peel to grate into cake mixtures and puddings, we felt frustrated every time we opened a cookery book or picked up a mixing bowl. In short, during the past four hundred years the lemon has become, in cooking, the condiment which has largely replaced the vinegar, the verjuice (preserved juice of green grapes), the pomegranate juice, the bitter orange juice, the mustard and wine compounds which were the acidifiers poured so freely into the cooking pots of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Europe. There are indeed times when a lemon as a seasoning seems second only in importance to salt.