Omelette and a Glass of Wine (27 page)

Read Omelette and a Glass of Wine Online

Authors: Elizabeth David

Tags: #Cookbooks; Food & Wine, #Cooking Education & Reference, #Essays, #Regional & International, #European, #History, #Military, #Gastronomy, #Meals

Simple French Cooking for English Homes

The chief thing to remember is that all these soups – unless otherwise specified – must be made with plain water. When made with the addition of stock they lose all character and cease to be what they were intended to be. The fresh pleasant taste is lost owing to the addition of meat stock, and the value of the soup from an economical point of view is also lost.

What Shall We Have Today?

That commodities such as simple sardine or anchovy butter which we had hitherto regarded as sandwich fillings, egg dishes which belonged to the breakfast table, the bed-sitting room or the night club, and little hot dishes which were ordinary English family supper savouries were valuable resources which could be quite differently deployed and offered as party dishes were ideas which had occurred to few people in pre-Boulestin days:

SARDINE BUTTER

‘Take a tin of sardines, carefully remove the skins and bones and pound well. Add same quantity of butter, salt and pepper. Mix thoroughly so that it becomes a smooth paste. Serve very cold. Quite ordinary sardines will do for this.’

The Evening Standard Book of Menus

Boulestin’s idea was that while you were at it you made – as in a great many of his recipes – enough of this mixture (he treats smoked cod’s roe and anchovy fillets in precisely the same manner) for two meals: you serve it as a first course, with toast, for two very differently composed lunches. On a Friday in January it is followed by Irish stew and cheese (not for me, that menu, but Boulestin had something for everybody), on Saturday by cold ham and pressed beef, a hot purée of leeks with croûtons as a separate course, and fruit. On an August Thursday he thinks of it again. It precedes a sauté of liver and bacon, potato croquettes and fruit salad. On the Saturday it is followed by a Spanish omelette, cheese and fruit. And bless him, it is delicious, his sardine butter, and marvellously cheap and quick. You allow, or at any rate, I allow, an ounce of butter per Portuguese sardine. Pack the paste into a little terrine, chill it – and

you will never again feel it necessary to go to the delicatessen for bought liver pâté or any such sub-standard hors d’œuvre.

From the same book come these two menus for September luncheons:

Salad of Tunny Fish and Celery

Risotto Milanaise

Fruit

———

Scrambled Eggs with Haddock

Vegetable Salad

Creamed Rice.

In those days only Boulestin thought of actually inviting people to lunch to eat scrambled eggs. It goes without saying that he did not serve scrambled eggs

with

smoked haddock, he cooked the haddock first, flaked it, and mixed it with the beaten eggs before cooking them. He added a little cream to the finished scrambled eggs and put fried croûtons round them. In January the same breakfast dish appears as a first course before the cold turkey and salad, the meal to be ended with English toasted cheese.

BRAISED VEAL WITH CARROTS

‘Take a good piece of veal, about three pounds in weight, brown it both sides in butter. Put in a fireproof dish eight carrots cut in round pieces, about half an inch thick, half a dozen small onions, parsley, salt and pepper and a rasher of bacon cut in small pieces, add a tablespoon of water, cover the dish and cook on a slow fire for about three and a half hours. Shake the dish occasionally, but do not remove the lid.’

The Conduct of the Kitchen

This recipe must have been one of Boulestin’s favourites. It appears over and over again in his books. His omission of detail was deliberate. It is impossible, he was in the habit of saying, to give precise recipes. And certainly precision – unless carried to the ultimate degree, as in Madame Saint-Ange’s

Livre de Cuisine

1

or Julia Child’s

Mastering the Art of French Cooking

1

– can be more misleading than vagueness. Boulestin was impatient of written detail. When he does specify precise quantities or times he is often

wrong. His special gift was to get us on the move, send us out to the butcher to buy that good piece of veal, into the kitchen to discover how delicate is the combination of veal, carrots, little onions, a scrap of bacon, seasonings and butter all so slowly and carefully amalgamated – and all done with butter and water alone. Three and a half hours for a three-pound piece of veal – and on top of the stove too – is an awful long time. At minimum heat and in a heavy well-closed pot stood on the floor of the oven rather than on a shelf, the timing would be however just about right. Most of us know enough about absentee cooking these days to work out such details for ourselves. Those who do not would I think be well advised to use Boulestin recipes in conjunction with a fully detailed work such as one of those mentioned. Where Boulestin never falters or misleads is in the sureness of his taste and the sobriety of his ingredients even when his recipes are new inventions. Anglophile he may have been. Not so much as he thought he was. His recipes could never be mistaken for anything but the recipes of an educated Frenchman.

It was, I think, Boulestin who introduced the English public to the Basque

pipérade.

A recipe for it or a description of this beguiling dish of peppers, onions, tomatoes and eggs appears in every one of his books, even down to the booklet commissioned from him by the Romary biscuit firm and which sold for sixpence. The briefest

pipérade

recipe is the one recorded in

Having Crossed the Channel

as it was blurted out by a tipsy smuggler one morning in a Basque inn on the Bidassoa. ‘

Vous faites cuire vos piments et vos tomates et vous … foutez vos œufs dedans

’ (This was later translated by Adair as ‘shove in your eggs’.)

In the same little volume Boulestin gives us an explanation of the old-fashioned French custom of serving a vegetable before the roast – an explanation which contains also some sound gastronomic advice:

We had at Aurillac, where we avoided the two main hotels, a delicious meal in a quite ordinary inn full of market people. Trout was on the menu, done in a rather unusual way, and a cabbage which was almost a revelation, firm, white, and beautifully seasoned; the meat was well-flavoured and tender, and the cheese perfection.

… There they still serve the vegetable course before the roast. This is constantly done, especially in small, old-fashioned towns; but the foreigner must not think that this is provincial lack of knowledge.

It is simply due to the fact that these little hotels have remained faithful to habits dating from 1840 or so. In those days dinners were much longer,

and there was always an entrée and a roast. It became the rule to serve the vegetable – a fairly plain dish – as a pleasant change after the usually rich taste of the entrée, as a kind of diversion after the sauce, and, so to speak, to clean the palate for the roast to come, the roast being always (it still is) accompanied by a green salad.

Having Crossed the Channel

1

As can be seen even from these brief extracts Boulestin did not by any means invariably advocate traditional French bourgeois or regional cooking. He was nothing if not open-minded, adapting English ingredients to his own purposes and forever exercising his gift for fantasy. A dish he calls Maltese curry – an unlikely and most interesting mixture of onions, tomatoes and fruit with eggs mixed in at the end of the cooking, rather in the

pipérade

manner – was another recipe he repeated in several of his books. It is given in

The Best of Boulestin

and was a feature of his restaurant menu. Another of his favourites seems to have been a tomato jam; this he uses for a sweet called Peaches Barbara with cream and kirschwasser and pistachio nuts. One may and one does read plenty of freakish recipes in cookery books. To dismiss them out of hand is a sign either of defective knowledge or lack of imagination on the reader’s part or of the author’s incapacity to convince. In the case of writers whose taste is to be trusted the very oddness of a recipe often means that here is something worth special investigation. It turns out that the tomato jam has great finesse of flavour and emerges as a most beautiful translucent cornelian-red preserve, delicious for a jam served in the French manner as a sweet with plain cream or fresh cream cheese. Fantasies these little dishes may be. Again we see that in their subtlety and the manner in which they are presented they are still French fantasies.

One indication of the effect produced by Boulestin’s recipes is that whenever a second-hand copy of one of his books turns up – and that is not often – one finds it scarred with pencil marks against the recipes which have been cooked by the previous owner and often, slipped somewhere among the pages, a list of dishes noted for future trial. One I commend to your attention is a

mousse de laitues

, a kind of soufflé of cooked lettuces, given in

The Finer Cooking

and reproduced in

The Best of Boulestin.

Another is a pickled oxtongue, plain-boiled and served hot with a very smooth purée of white turnips enriched with butter and slices of hard-boiled egg. This was one of the original and unique specialities of the Boulestin

restaurant. The recipe which, under the name of

langue savoyarde

again appears in several of his books, is to be found in

The Best of Boulestin.

So is the formula for the famous cheese soufflé which so wonderfully conceals melting whole poached eggs, an old dish of French cookery and one served by Boulestin at a luncheon given at his restaurant to celebrate the publication by Cassells on 26 September 1936, of the autobiography entitled

Myself, My Two Countries.

An uncommonly good lunch it must have been that day. The wine was a Cheval Blanc 1925 and the sole liqueur was Armagnac. A modest show as press luncheons given by famous restaurateurs go. So was the luncheon given at Boulestin’s by a party of American journalists in honour of M. Aristide Briand. Somehow Boulestin contrived to persuade these gentlemen that the great statesman, surfeited with political banquets and pompous food, would appreciate something simple and at least one dish and one wine from his native Nantais country. Where today, one wonders, would a visiting celebrity be allowed so unceremonial a ceremonial meal, and one with so much character? Less than perfect, such a meal could indeed be a memorable flop. That Boulestin recorded the menu and the occasion indicates, one deduces, that it was no such thing:

Hors d’Œuvre

Omelette au crabe

Chou farci

Fromages et Fruits

Vins:

Muscadet 1928

Château Gruaud Larose 1923

The Finer Cooking

1

At the premises in Southampton Street, Covent Garden, to which the Boulestin Restaurant moved from Leicester Square there exists still today an establishment which bears Boulestin’s name. The Dufy panels and some of the original decorations still exist. Its founder, was, I think, the first amateur to venture on a London restaurant and certainly the only one to acquire an international reputation for his food. In

Ease and Endurance

,

2

the continuation of the autobiography which Boulestin wrote in French under the title of

A Londres Naguère

and which was published after his death in a somewhat harum-scarum translation by Robin Adair (at one point

Adair has Boulestin exploring the Cecil Hotel in a taxi), he tells how the place was crammed night after night with customers from the Savoy, Ritz and Carlton belt, stage stars, artists, writers, royalty and High Bohemia. His prices were reputed to be the highest in London. And still the restaurant did not pay. Boulestin had found, like so many before and since, that in England the price of perfection is too high. During most of the fourteen years that he was running his restaurant he found it necessary to supplement his earnings by articles, books – heaven knows how he found the time to write them – cookery classes, lectures and the television demonstrations which were the first of their kind.

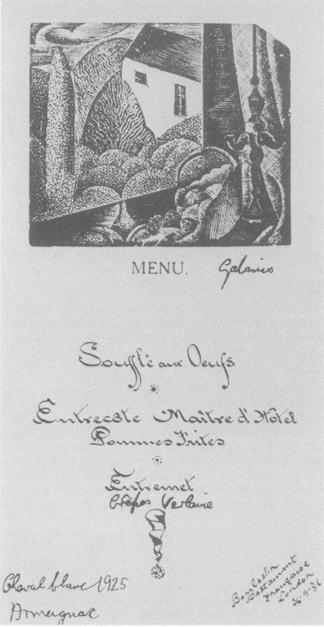

A 1936 menu for the Boulestin restaurant in London, in the possession of the author

*

One final passage from

Myself, My Two Countries

vividly evokes the influences which formed Boulestin’s tastes in food and implanted in him that feeling for the authenticity which alone is true luxury. Here he remembers the kitchen quarters of his grandmother’s house at St Aulaye in the Périgord:

In the store room next to the kitchen were a long table and shelves always covered with all sorts of provisions; large earthenware jars full of

confits

of pork and goose, a small barrel where vinegar slowly matured, a bowl where honey oozed out of the comb, jams, preserves of sorrel and of tomatoes, and odd bottles with grapes and cherries marinating in brandy; next to the table a weighing machine on which I used to stand at regular intervals; sacks of haricot beans, of potatoes; eggs, each one carefully dated in pencil.