Omelette and a Glass of Wine (26 page)

Read Omelette and a Glass of Wine Online

Authors: Elizabeth David

Tags: #Cookbooks; Food & Wine, #Cooking Education & Reference, #Essays, #Regional & International, #European, #History, #Military, #Gastronomy, #Meals

Wine and Food

, Summer 1964

1.

It is difficult enough to lay hands on genuine Swiss Gruyère, let alone the Comtois version; but Bartholdi’s, the Swiss shop at 4 Charlotte Street, London, W.I, can usually supply the authentic Swiss article, and I have bought the delicious Beaufort cheese from Paxton and Whitfields’ in Jermyn Street. Fontina, the Val d’Aosta cheese required for the Piedmontese

fonduta

, is sometimes to be found at Soho shops such as Lina’s in Brewer Street, and King Bomba’s and Parmigiani Brothers of Old Compton Street.

THE WORK OF X. MARCEL BOULESTIN

A refugee from the Colette-Willy ménage of the early nineteen hundreds, from what promised to be a long stint of sterile work as Willy’s secretary and as yet another among the throng of that extraordinary man’s unacknowledged collaborators, the young Marcel Boulestin fled the malicious gossip, the dramas and scandals in which these two now legendary figures were for ever involving each other and their friends. Avoiding the recriminations which he knew would ensue should he inform Willy of his decision, Boulestin slipped away from Paris while his employer was absent. Thenceforth he made his life in England.

As a result of two previous visits to London, Boulestin had already gone through a period of serious anglomania which extended even to our food, and an attempt to make his father’s household in Poitiers appreciate the beauty of mint sauce with mutton, the fascination of Sir Kenelm Digby’s Stuart recipes for hydromel and mead, and the anglo-oriental romance of curry as served at Romano’s. In Paris he bought mince pies and English marmalade, took Colette to tea at the British Dairy, shared a blazing plum pudding with her at Christmas, drank whisky instead of wine at a dinner party at Fouquet’s, spent two summer holidays in Dieppe because it was so English, and there made friends with Walter Sickert, William Nicholson, Reggie Turner, Ada Leverson, Marie Tempest and Max Beerbohm. As a result he did a French translation of

The Happy Hypocrite

which was published in 1904 by the

Mercure de France

, illustrated with a caricature of Boulestin by Max (Boulestin had some difficulty in convincing the

Mercure

’s editor that Max Beerbohm actually existed and was not an invention of his own).

At the time of the Beerbohm translation Boulestin was already a writer and journalist of some experience. Before his Colette-Willy period he had contributed a weekly column of musical criticism to a

Bordeaux newspaper. Willy was an astute talent-spotter. The young men who made up his troupe of ghosts were seldom nonentities. I have been told by Mr Gerald Hamilton that Boulestin’s novel called

Les Fréquentations de Maurice

, published about 1910, is highly entertaining. In France the book had quite a

succès de scandale.

Dealing with the life of a gigolo it was considered altogether too fast for the English public.

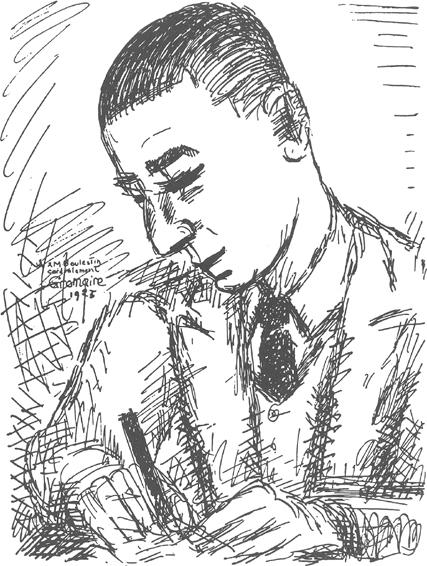

Marcel Boulestin, by Gromaire, London, 1925, reproduced in

Myself, My Two Countries

It was not until after the 1914 war and nearly five years with the French army – although domiciled in England for some thirty years he never at any time entertained the idea of becoming a naturalized British subject, considering it highly improper for a Frenchman to renounce his country – and following the failure of his London decorating business, which before the war had been successful, that Boulestin turned to cookery writing.

In the first years of the twenties Boulestin had been dabbling, in a small way, in picture dealing, starting off promisingly with a Modigliani bought in Paris for

£

12 and sold in London for

£

90. Returning to interior decorating he imported French wallpapers and fabrics designed by Poiret and Dufy. He found his English customers unready for such innovations. Before long he was broke. During the course of negotiating the sale of some etchings by his friend J. E. Laboureur to Byard, a director of Heinemann’s, Boulestin asked if a cookery book would be of any interest at that moment. It would, said Byard. On the spot a contract was produced and signed. An advance of

£

10 was paid over.

Boulestin’s writing still seems so fresh and original that it comes as a shock to realize that these happenings occurred over forty years ago, and that his first cookery book

Simple French Cooking for English Homes

appeared in 1923. On the plain white jacket of the little book, and as a frontispiece, was a design, enticing, fresh and lively, by Laboureur. The book, priced at 5s., was reprinted in September of the same year, again in 1924, 1925, 1928, 1930 and 1933. In the meantime Boulestin had written cookery articles for the

Daily Express

, the

Morning Post, Vogue

, the

Manchester Guardian

and the

Spectator;

in February 1925

A Second Helping

was published, also with a Laboureur jacket and frontispiece. It was uncommon in those days, and still is, for publishers to commission artists of such quality to illustrate cookery books, and a little of the success of Boulestin’s early books must be acknowledged to his publishers who, no doubt under the guidance of their author,

produced them in so appropriate a form, in large type, on thick paper: chunky, easy little books to handle, attractively bound. (To the general reader such matters may appear trifling. From the point of view of a book being lastingly used and loved the effect of the Tightness and appropriateness as a whole is enormous.)

A Second Helping

is perhaps the least successful of Boulestin’s books. A certain proportion of ‘amusing’ recipes and chic asides ‘get your rabbits sent from Dartmoor’ give it a distinct whiff of the fashion-magazine hostess style. Later the same year appeared, for 3s. 6d.,

The Conduct of the Kitchen.

In that year also the first Boulestin restaurant was opened in Leicester Square. Again, artists and innovators in the decorating business collaborated with Boulestin. Allan Walton, the enlightened owner of a prosperous textile firm in the Midlands, produced a friend who produced the capital for the restaurant, and supplied also the fabrics (he was employing artists of the stature of Cedric Morris, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant to design for him) with which the restaurant was furnished.

In 1930 Boulestin collaborated with Jason Hill on

Herbs, Salads and Seasonings

, illustrated with unique grace by Cedric Morris. In 1931 came

What Shall We Have Today?

(5s. and in paper covers 3s.), the most popular of all the Boulestin books, containing a large selection of recipes plus a sample luncheon and dinner menu for each month of the year. In 1932, in collaboration with Robin Adair, appeared three little volumes at is. each, dealing with

Savouries and Hors-d’Œuvre, Eggs

and

Potatoes.

Reprinted by Heinemann in 1956, these little books are still (or were last year) available at 2s. 6d. each. The grotesquely inappropriate and anti-food coloured board covers have presumably hampered their sales even at what is today a give-away price.

In 1934 came

Having Crossed the Channel

, a lighthearted record of a journey through the Vendée, the Landes, the Bordelais, a pilgrimage back to his native Périgord and into his youth, a drive across central France, down to the coast, into Italy and Southern Germany and back via Belgium and Holland. This little nugget of a book (but all Boulestin books are nuggets) contains some of Boulestin’s best writing about his own province and about the food of obscure country inns of a type now all but vanished. In this book also are the best illustrations Laboureur ever did for Boulestin, one being of the archetype of the French small-town restaurant, the wide, shuttered window, the tree in a tub on the pavement, the façade which has not changed and which still promises decent and

genuine country cooking at modest prices. That you may find neither when you get inside is another matter. The evocation is there.

In 1935 Boulestin’s

Evening Standard Book of Menus

was published by Heinemann. This book is in its way a

tour de force.

It contains a luncheon and dinner menu for every day of the year, plus every relevant recipe. It was directed at an audience to which a man of lesser wit and native grace might have been tempted to talk down (it has to be remembered that by this time Boulestin and his restaurant had already become almost legendary) but this was a trap into which he was at the same time too subtle and too naturally courteous to fall. What he produced was a volume for which he really should have kept his title

The Conduct of the Kitchen

– a title borrowed incidentally from Meredith – because that was just what the book of menus was about: the logical and orderly conduct of a kitchen as related to daily life and seen not through the medium of a few isolated menus for special occasions, but as part of the natural order of everyday living. Given time, Boulestin could perhaps with his book of menus have opened the door to organized cooking for thousands of young women who in the thirties were finding themselves on their own in flats and bed-sitting rooms knowing nothing more about how to make a meal than that it ought to taste nice and should not be a bore. As things turned out, time was something not just then at our disposal. Very soon we were to be concerned with matters less peaceful than the conduct of our kitchens.

In the summer of 1939 Boulestin left as usual to spend his holidays in the house he had built for himself in the Landes. Caught by the outbreak of war he and Robin Adair lingered, not knowing what to do. Boulestin’s services, offered to the British Ministry of Food and to the Army Quartermaster General, were refused. When France fell Adair was too ill to flee and Boulestin of course stayed with him. Arrested and interned by the Germans, Adair was eventually moved from Bayonne to Fresne. Boulestin went to live in occupied Paris to be near his friend. There, on 22nd September 1943, he died, aged, so Adair tells us, sixty-five.

*

M. André Simon, Boulestin’s compatriot and contemporary, writing two years ago of Boulestin’s rule that all wines young or old, red or white must be served in a decanter, recorded that ‘he never liked the shape and colour of wine bottles standing on the table: they

were of the greatest use, of course, but their right place was the cellar or pantry’. ‘He was a born artist,’ says M. Simon of Boulestin, ‘and he was right.’

*

Quotation is my only means of conveying something of that artistry, of the essence of Boulestin’s writing, of his intelligence, sense and taste, of his ease of style, un-scolding, un-pompous, un-sarcastic, ineffusive, and to so high a degree inspiriting and creative.

The handful of extracts, words of kitchen advice, recipes, menus, and descriptive passages I have chosen to quote are none of them to be found in

The Best of Boulestin

, the American-selected anthology published in England by Heinemann in 1952 and still available at 21s. This volume does indeed contain many of Boulestin’s best recipes, but not one single one of the delicious menus in the composition of which he excelled; and it was a mistake for the editors to suppose that they understood French syntax better than their author. Boulestin was no illiterate peasant: when he called a recipe

sauce moutarde

he did so because that is correct French. There was no call to make him look like an Anglo-Saxon writing in schoolboy French by altering it to

sauce de moutarde.

For that matter little seems to have been gained by the translation of

gâteau petit duc

into Little Duke Cake and

crêpes normandes

into French pancakes Normande. At any rate anybody who buys

The Best of Boulestin

should be warned to pay no attention to the announcement on the jacket which informs us that the book contains a selection of the best recipes of a ‘World-Famous Chef’. A chef in the professional sense of the word is just exactly what Boulestin was not and certainly did not pretend to be. The implications of that piece of grandiloquence would not have been at all to his taste, as anyone can see from reading a paragraph or two of any of his books. It would be a mistake for anyone to infer that Boulestin was a man who had no more sense than to attempt amateur cooking in his own restaurant. He hired an experienced French chef (his name was Bigorre. He came from Paillard’s in Paris), but not one who would substitute an arid classicism for personal taste and character in his cooking. Boulestin was not out to emulate Escoffier. He was creating something new, as much in his restaurant as in his cookery writing. In his very first book his admonitions about the indiscriminate use of stock, even of fine stock, were news, and good news:

Do not spoil the special taste of the gravy obtained in the roasting of beef, veal, mutton or pork by adding to it the classical stock which gives to all meats the same deplorable taste of soup. It is obvious that you cannot out of a joint get the sauceboat full which usually appears on the table.