On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (20 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

Chapter Three

Emotional Distance: "To Me They Were Less

than Animals"

Increasing the distance between the [combatants] — whether by emphasizing their differences or by increasing the chain of responsibility between the aggressor and his victim allows for an increase in the degree of aggression.

— Ben Shalit

The Psychology of Conflict and Combat

Cracks in the Veil of Denial

O n e evening after giving a presentation on " T h e Price and Process of Killing" to a group of vets in N e w York, I was asked by a retired World War II veteran w h o had been in the audience if I could talk with him privately in the bar. After we were alone he said that there was something he had never told anyone about, something that, after hearing my presentation, he wanted to share with me.

He had been an army officer in the South Pacific, and one night the Japanese launched an infiltration attack on his position. During the attack a Japanese soldier charged him.

"I had my forty-five [-caliber pistol] in my hand," he said, "and the point of his bayonet was no further than you are from me

EMOTIONAL DISTANCE

157

when I shot him. After everything had settled down I helped search his body, you know, for intelligence purposes, and I found a photograph."

Then there was a long pause, and he continued. "It was a picture of his wife, and these two beautiful children. Ever since" — and here tears began to roll down his cheeks, although his voice remained firm and steady — "I've been haunted by the thought of these two beautiful children growing up without their father, because I murdered their daddy. I'm not a young man anymore, and soon I'll have to answer to my Maker for what I have done."1

A year later, in a pub in England, I told a Vietnam veteran who is currently a colonel in the U.S. Army about this incident. As I told him about the photographs he said, "Oh, no. Don't tell me.

There was an address on the back of the photo."

"No," I replied. "At least he never mentioned it if there was."

Later in the evening I got back around to asking why he would have thought there was an address on the photos, and he told me that he had had a similar experience in Vietnam, but his photos had addresses on the back of them. "And you know," he said, as his eyes lost focus and he slipped into that haunted, thousand-yard stare I've seen in so many vets when their minds and emotions return to the battlefield, "I've always meant to send those photos back."

158

A N A N A T O M Y O F KILLING

Each of these men had attained the rank of colonel in the U.S.

Army. Both are the distilled essence of all that is good and noble in their generation. And both of them have been haunted by simple photographs. But what those photographs represented was a crack in the veil of denial that makes war possible.

The Social Obstacles to Emotional Distance

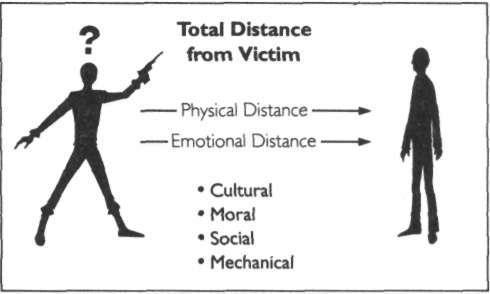

The physical distance process has been addressed previously, but distance in war is not merely physical. There is also an emotional distance process that plays a vital part in overcoming the resistance to killing. Factors such as cultural distance, moral distance, social distance, and mechanical distance are just as effective as physical distance in permitting the killer to deny that he is killing a human being.

There was a popular and rather clever saying during the 1960s that asked, "What if they gave a war and nobody came?" This is not quite as ludicrous a concept as it may seem on the surface.

There is a constant danger on the battlefield that, in periods of extended close combat, the combatants will get to know and acknowledge one another as individuals and subsequently may refuse to kill each other. This danger and the process by which it can occur is poignantly represented by Henry Metelmann's account of his experiences as a German soldier on the Russian front during World War II.

There was a lull in the battle, during which Metelmann saw two Russians coming out of their foxhole,

and I walked over towards them . . . they introduced themselves

. . . [and] offered me a cigarette and, as a non-smoker, I thought if they offer me a cigarette I'll smoke it. But it was horrible stuff.

I coughed and later on my mates said "You made a horrible impression, standing there with those two Russians and coughing your head off." . . . I talked to them and said it was all right to come closer to the foxhole, because there were three dead Russian soldiers lying there, and I, to my shame, had killed them. They wanted to get the [dog tags] off them, and the paybooks. . . . I kind of helped them and we were all bending down and we found E M O T I O N A L D I S T A N C E

159

some photos in one of the paybooks and they showed them to me: we all three stood up and looked at the photos. . . . We shook hands again, and one patted on my back and they walked away.

Metelmann was called away to drive a half-track back to the field hospital. W h e n he returned to the battlefield, over an hour later, he found that the Germans had overrun the Russian position. And although there were some of his friends killed, he found himself to be most concerned about what happened to "those two Russians."

"Oh they got killed," they said.

I said: "How did it happen?"

"Oh, they didn't want to give in. Then we shouted at them to come out with their hands up and they did not, so one of us went over with a tank," he said, "and really got them, and silenced them that way." My feeling was very sad. I had met them on a very human basis, on a comradely basis. They called me comrade and at that moment, strange as it may seem, I was more sad that they had to die in this mad confrontation than my own mates and I still think sadly about it.

This identification with one's victim is also reflected in the Stockholm syndrome. Most people know of the Stockholm syndrome as a process in which the victim of a hostage situation comes to identify with the hostage taker, but it is actually more complex than that and occurs in three stages:

• First the

victim

experiences an increase in association with the hostage taker.

• Then the victim usually experiences a decrease in identification with the authorities w h o are dealing with the hostage taker.

• Finally the

hostage taker

experiences an increase in identification and bonding with the victim.

O n e of the more interesting of many such cases was the Moluccan train siege in Holland in 1975, In this instance the terrorists had already shot one hostage and then selected another for execution.

This intended victim then asked permission to write a final note to his family, and his request was granted. He was a journalist, 160 AN ANATOMY OF KILLING

and he must have been a very good one, for he wrote such a heart-wrenching letter that, upon reading it, the terrorists took pity on him . . . and shot someone else instead.

Sometimes this process can happen on a vast scale. Many times in World War I there were unofficial suspensions of hostilities that came about through the process of coming to know each other too well. During Christmas of 1914 British and German soldiers in many sectors met peacefully, exchanged presents, took photographs and even played soccer. Holmes notes that "in some areas the truce went on until well into the New Year, despite the High Command's insistence that it should be war as usual."

Erich Fromm states that "there is good clinical evidence for the assumption that destructive aggression occurs, at least to a large degree, in conjunction with a momentary or chronic emotional withdrawal." The situations described above represent a breakdown in the psychological distance that is a key method of removing one's sense of empathy and achieving this "emotional withdrawal." Again, some of the mechanisms that facilitate this process include:

• Cultural distance, such as racial and ethnic differences, which permit the killer to dehumanize the victim

• Moral distance, which takes into consideration the kind of intense belief in moral superiority and vengeful/vigilante actions associated with many civil wars

• Social distance, which considers the impact of a lifetime of practice in thinking of a particular class as less than human in a socially stratified environment

• Mechanical distance, which includes the sterile Nintendo-game unreality of killing through a TV screen, a thermal sight, a sniper sight, or some other kind of mechanical buffer that permits the killer to deny the humanity of his victim

Cultural Distance: "Inferior Forms of Life"

In the section "Killing in America," we will examine the methodology a U.S. Navy psychiatrist developed to psychologically enable assassins for the U.S. Navy. This "formula" primarily involved E M O T I O N A L D I S T A N C E

161

classical conditioning and systematic desensitization using violent movies, but it also integrated cultural distance processes in order to get the men to think of the potential enemies they will have to face as inferior forms of life [with films] biased to present the enemy as less than human: the stupidity of local customs is ridiculed, local personalities are presented as evil demigods.

— quoted in Peter Watson,

War on the Mind

The Israeli research mentioned earlier indicates that the risk of death for a kidnap victim is much greater if the victim is hooded.

Cultural distance is a form of emotional hooding that can work just as effectively. Shalit notes that "the nearer or more similar the victim of aggression is, the more we can identify with him." And the harder it is to kill him.

This process also works the other way around. It is so much easier to kill someone if they look distinctly different from you.

If your propaganda machine can convince your soldiers that their opponents are not really human but are "inferior forms

of life,"

then their natural resistance to killing their own species will be reduced. Often the enemy's humanity is denied by referring to him as a "gook," "Kraut," or "Nip." In Vietnam this process was assisted by the "body

count"

mentality, in which we referred to and thought of the enemy as numbers. One Vietnam vet told me that this permitted him to think that killing the NVA and VC was like "stepping on ants."

The greatest master of this in recent times may have been Adolf Hitler, with his myth of the Aryan master race: the

Ubermensch,

whose duty was to cleanse the world of the

Untermensch.

The adolescent soldier against whom such propaganda is directed is desperately trying to rationalize what he is being

forced

to do, and he is therefore predisposed to believe this nonsense. Once he begins to herd people like catlle and then to slaughter them like cattle, he very quickly begins to think of them as cattle — or, if you will,

Untermensch.

According to Trevor Dupuy, the Germans, in all stages of World War II, consistently inflicted 50 percent more casualties on 162 AN ANATOMY OF KILLING

the Americans and British than were inflicted on them. And the Nazi leadership would probably be the first to tell you that it was this carefully nurtured belief in their racial and cultural superiority that enabled the soldiers to be so successful. (But, as we shall see in "Killing and Atrocities," this enabling also contained an entrap-ment that contributed gready to the Nazis' ultimate defeat.) But the Nazis are hardly the only ones to wield the sword of racial and ethnic hatred in war. European imperial defeat and domination of "the darker races" was facilitated by cultural distance factors.

However, this can be a double-edged sword. Once oppressors begin to think of their victims as not being the same species, then these victims can accept and use that cultural distance to kill and oppress their colonial masters when they finally gain the upper hand. This double-edged sword was turned on the oppressors when colonial nations rose up in fierce insurrections such as the Sepoy Mutiny or the Mau Mau Uprising. In the final battles that overthrew imperialism around the world, the backlash of this double-edged sword was a major factor in empowering local populations.

The United States is a comparatively egalitarian nation and therefore has a little more difficulty getting its population to whole-heartedly embrace wartime ethnic and racial hatreds. But in combat against Japan we had an enemy so different and alien that we were able to effectively implement cultural distance (combined with a powerful dose of moral distance, since we were "avenging" Pearl Harbor). Thus, according to Stouffer's research, 44 percent of American soldiers in World War II said they would "really like to kill a Japanese soldier," but only 6 percent expressed that degree of enthusiasm for killing Germans.

In Vietnam cultural distance would have back-lashed against us, since our enemy was racially and culturally indistinguishable from our ally. Therefore we tried hard (at a national policy level) not to emphasize any cultural distance from our enemies. The primary psychological distance factor utilized in Vietnam was moral distance, deriving from our moral "crusade" against communism.