On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (19 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

of his men, and he must live forevermore with what he has done to those who entrusted their lives to his care. When I interview combatants, many tell of remorse and anguish that they have never told anyone of before. But I have not yet had any success at getting a leader to confront his emotions revolving around the soldiers who have died in combat as a result of his orders. In interviews, such men work around reservoirs of guilt and denial that appear to be buried too deeply to be tapped, and perhaps this is for the best.

The Lost Battalion of World War I is a famous example of a unit that was sustained by its leader's will. This unit, a battalion of the 77th Division, was cut off and surrounded by Germans during an attack. They continued to fight for days. They ran out of food, water, and ammunition. The survivors were surrounded by friends and comrades suffering from horrible wounds that could not receive medical attention until they surrendered. The Germans brought up flamethrowers and tried to burn them out. Still their commander would not surrender.

They were not an elite or specially trained unit. They were only a composite infantry battalion made up of citizen-soldiers in a National Guard Division. Yet they performed a feat that will shine forever in the annals of military glory.

All the survivors gave full credit for their achievement to the incredible fortitude of their battalion commander, Major C. W.

Whittlesey, who refused to surrender and constantly encouraged the dwindling survivors of his battalion to fight on. After five days their battalion was rescued. Major Whittlesey was given the Congressional Medal of Honor. Many people know this story.

What they don't know is that Whittlesey committed suicide shortly after the war.

Chapter Two

Group Absolution: "The Individual Is Not a Killer,

but the Group Is"

Disintegration of a combat unit . . . usually occurs at the 50%

casualty point, and is marked by increasing numbers of individuals refusing to kill in combat. . . . Motivation and will to kill the enemy has evaporated along with their peers and comrades.

— Peter Watson

War on the Mind

A tremendous volume of research indicates that the primary factor that motivates a soldier to do the things that no sane man

wants

to do in combat (that is, killing and dying) is not the force of self-preservation but a powerful sense of accountability to his comrades on the battlefield. Richard Gabriel notes that "in military writings on unit cohesion, one consistently finds the assertion that the bonds combat soldiers form with one another are stronger than the bonds most men have with their wives." The defeat of even the most elite group is usually achieved when so many casualties have been inflicted (usually somewhere around the 50 percent point) that the group slips into a form of mass depression and apathy. Dinter points out that " T h e integration of the individual in the group is so strong sometimes that the group's destruction, e.g. by force or

150

A N A N A T O M Y O F KILLING

captivity, may lead to depression and subsequent suicide." Among the Japanese in World War II this manifested itself in mass suicide.

In most historical groups it results in the group suicide of surrender.

Among men w h o are bonded together so intensely, there is a powerful process of peer pressure in which the individual cares so deeply about his comrades and what they think about him that he would rather die than let them down. A U.S. Marine Corps Vietnam vet interviewed by Gwynne Dyer communicated this process clearly when he said that "your first instinct, regardless of all your training, is to live. . . . But you can't turn around and run the other way. Peer pressure, you know?" Dyer calls this "a special kind of love that has nothing to do with sex or idealism," and Ardant du Picq referred to it as "mutual surveillance" and considered it to be the predominant psychological factor on the battlefield.

Marshall noted that a single soldier falling back from a broken and retreating unit will be of little value if pressed into service in another unit. But if a pair of soldiers or the remnants of a squad or platoon are put to use, they can generally be counted upon to fight well. The difference in these two situations is the degree to which the soldiers have bonded or developed a sense of accountability to the small number of men they will be fighting with —

which is distinctly different from the more generalized cohesion of the army as a whole.

If

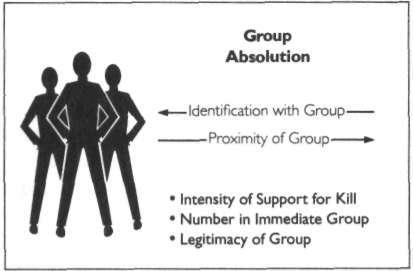

the individual is bonded with his G R O U P A B S O L U T I O N 151

comrades, and //"he is with "his" group, then the probability that the individual will participate in killing is significantly increased.

But if those factors are absent, the probability that the individual will be an active participant in combat is quite low.

Du Picq sums this matter up when he says, "Four brave men w h o do not know each other will not dare to attack a lion. Four less brave, but knowing each other well, sure of their reliability and consequently of mutual aid, will attack resolutely. There,"

says du Picq, "is the science of the organization of armies in a nutshell."

Anonymity and Group Absolution

In addition to creating a sense of accountability, groups also enable killing through developing in their members a sense of anonymity that contributes further to violence. In some circumstances this process of group anonymity seems to facilitate a kind of atavistic killing hysteria that can also be seen in the animal kingdom. Kruck's 1972 research describes scenes from the animal kingdom that show that senseless and wanton killing does occur. These include the slaughter of gazelles by hyenas, in quantities way beyond their need or capacity to eat, or the destruction of gulls that could not fly on a stormy night and thus were "sitting ducks" for foxes that proceed to kill them beyond any possible need for food. Shalit points out that "such senseless violence in the animal world — as well as most of the violence in the human domain — is shown by groups rather than by individuals."

Konrad Lorenz tells us that "man is not a killer, but the group is." Shalit demonstrates a profound understanding of this process and has researched it extensively:

All crowding has an intensifying effect. If aggression exists, it will become more so as a result of crowding; if joy exists, it will become intensified by the crowd. It has been shown by some studies . . .

that a mirror in front of an aggressor tends to increase his aggression — if he was disposed to be aggressive. However, if this individual were not so disposed, the effect of the mirror would be to further enhance his nonaggressive tendencies. The effect of the 152 AN ANATOMY OF KILLING

crowd seems to be much like a mirror, reflecting each individual's behavior in those around him and thus intensifying the existing pattern of behavior.

Psychologists have long understood that a diffusion of responsibility can be caused by the anonymity created in a crowd. It has been demonstrated in literally dozens of studies that bystanders will be less likely to interfere in a situation in direct relationship to the numbers who are witnessing the circumstance. Thus, in large crowds, horrendous crimes can occur but the likelihood of a bystander interfering is very low. However, if the bystander is alone and is faced with a circumstance in which there is no one else to diffuse the responsibility to, then the probability of intervention is very high. In the same way groups can provide a diffusion of responsibility that will enable individuals in mobs and soldiers in military units to commit acts that they would never dream of doing as individuals, acts such as lynching someone because of the color of his skin or shooting someone because of the color of his uniform.

Death in the Crowd: Accountability and Anonymity

on the Battlefield

The influence of groups on killing occurs through a strange and powerful interaction of accountability and anonymity. Although at first glance the influence of these two factors would seem to be paradoxical, in actuality they interact in such a manner as to magnify and amplify each other in order to enable violence.

Police are aware of these accountability and anonymity processes and are trained to unhinge them by calling individuals within a group by name whenever possible. Doing so causes the people so named to reduce their identification with the group and begin to think of themselves as individuals with personal accountability.

This inhibits violence by limiting the individuals' sense of accountability to the group and negating their sense of anonymity.

Among groups in combat, this accountability (to one's friends) and anonymity (to reduce one's sense of personal responsibility for killing) combine to play a significant role in enabling killing.

G R O U P A B S O L U T I O N

153

As we have seen so far in this study, killing another human being is an extraordinarily difficult thing to do. But if a soldier feels he is letting his friends down if he doesn't kill, and if he can get others to share in the killing process (thus diffusing his personal responsibility by giving each individual a slice of the guilt), then killing can be easier. In general, the more members in the group, the more psychologically bonded the group, and the more the group is in close proximity, the more powerful the enabling can be.

Still, just the presence of a group in combat does not guarantee aggression. (It could be a group of pacifists, in which case pacifism might be enabled by the group!) T h e individual must identify with and be bonded with a group that has a legitimate demand for killing. And he must be with or close to the group for it to influence his behavior.

Chariot, Phalanx, Cannon, and Machine Gun: The Role of

Groups in Military History

These processes can be seen throughout military history. For example, military historians have often wondered why the chariot dominated military history for so long. Tactically, economically, and mechanically it was not a cost-effective instrument on the battlefield, yet for many centuries it was the king of battle. But if we examine the psychological leverage provided by the chariot to enable killing on the battlefield, we soon realize that the chariot was successful because it was the first crew-served weapon.

Several factors were at play here — the bow as a distance weapon, the social distance created by the archers' having come from the nobility, and the psychological distance created by using the chariot in pursuit and shooting men in the back — but the key issue is that the chariot crew traditionally consisted of two men: a driver and an archer. And this was all that was needed to provide the same accountability and anonymity in close-proximity groups that in World War II permitted nearly 100 percent of crew-served weapons (such as machine guns) to fire while only 15 to 20 percent of the riflemen fired.

T h e chariot was defeated by the phalanx, which succeeded by turning the whole formation into a massive crew-served weapon.

154

A N A N A T O M Y O F KILLING

Although he did not have the designated leaders of the later Roman formations, each man in the phalanx was under a powerful mutual surveillance system, and in the charge it would be hard to fail to strike home without having others notice that your spear had been raised or dropped at the critical moment. And, of course, in addition to this accountability system the closely packed phalanx provided a high degree of mob anonymity.

For nearly half a millennium the Romans' professional military (with, among other things, their superior application of leadership) eclipsed the phalanx in the Western way of war. But the phalanx's application of group processes was so simple and so effective that during the period of more than a thousand years between the fall of the Roman Empire and the full integration of gunpowder, the phalanx and the pike ruled infantry tactics.

And when gunpowder was introduced, it was the crew-served cannon, later augmented by the machine gun, that did most of the killing. Gustavus Adolphus revolutionized warfare by introducing a small three-pound cannon that was pulled around by each platoon, thus becoming the first platoon crew-served weapon and presaging the platoon machine guns of today. Napoleon, an artilleryman, recognized the role of the artillery (often firing grapeshot at very close ranges), which was the real killer on the battlefield, and throughout his years he consistently ensured that he had greater numbers of artillery than any of his opponents. During World War I the machine gun was introduced and termed the "distilled essence of the infantry," but it really was the continuation of the cannon, as artillery became an indirect-fire weapon (shooting over the soldiers' heads from miles back), and the machine gun replaced the cannon in the direct-fire, mid-range role.

Britain's World War I Machine Gun Corps Monument, next to the Wellington Monument in London, is a statue of a young David, inscribed with a Bible verse that exemplifies the meaning of the machine gun in that terrible war that sucked so much of the marrow from the bones of that great nation: Sol has slain his thousands

And David has slain his tens of thousands.

G R O U P A B S O L U T I O N 155

"They Were Killing My Friends": Groups on the

Modern Battlefield

T h e influence of groups can be seen clearly when we closely examine the killing case studies outlined throughout this book.

N o t e the absence of group influence in many of the situations in which combatants chose

not

to kill each other. For example, in the section "Killing and Physical Distance," Captain Willis was alone when he was suddenly confronted with a single N o r t h Vietnamese soldier. He "vigorously shook his head" and initiated "a truce, cease-fire, gentleman's agreement or a deal," after which the enemy soldier "sank back into the darkness and Willis stumbled o n . "

Again, at the beginning of the section "Killing and the Existence of Resistance," Michael Kathman, a tunnel rat crawling alone in a Vietcong tunnel, was alone when he switched on the light and suddenly found "not more than 15

feet

away . . . a [lone] Viet C o n g eating a handful of rice. . . . After a moment, he put his pouch of rice on the floor of the tunnel beside him, turned his back to me and slowly started crawling away." Kathman, in turn, switched off his flashlight and slipped away in the other direction.

And as you read these case studies note also the presence and influence of groups in most situations in which soldiers

do

elect to kill. T h e classic example is Audie Murphy, the most decorated American soldier of World War II. He w o n the Medal of H o n o r by single-handedly taking on a German infantry company. He fought alone, but when asked what motivated him to do this, he responded simply, " T h e y were killing my friends."