Organize Your Mind, Organize Your Life (10 page)

Read Organize Your Mind, Organize Your Life Online

Authors: Margaret Moore

Notice in these examples how there are variables within your control that can add or reduce the frenzy in your life. In this example, the working mom whose stress we've graphed could reduce the frenzy in her life by trying to walk more often at lunchtime and by sharing more of the after-dinner parenting chores with her spouse.

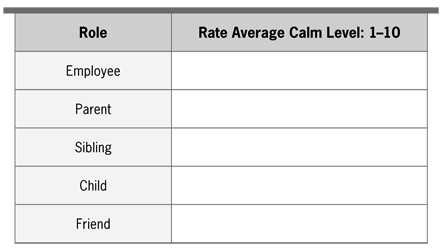

Another approach to the thirty-thousand-foot level is to identify the main roles you play in lifeâboss, parent, sibling, child, friendâand think about the frequency of moments of calm or frenzy when you're in each role. Which role brings the calmest moments, and which stirs up the greatest frenzy?

As you become more mindful and aware of your moments of calm and frenzy, you'll be able to “own” your role, your responsibility and your ability to increase calm and decrease frenzy. You may realize that you are truly in a state of burnoutâalmost always frenzied and rarely calm. Or it may be sporadicâsome days, some weeks or some recurring phases of daily life, such as the business demands of month or quarter end.

The more you understand your calm and frenzy patterns, the better you will be at removing or reducing the sources of frenzy, getting in control of your response to external or internal frenzy, or eliciting calm. Define your ideal state of calm when you are in control of frenzy.

When are you at your most calm and peaceful? What circumstances lead to an energetic yet calm state? What's your ideal? If you could wake up tomorrow morning in a calm state, how would that feel? What would your life be like if you felt calm twice as frequently as you do now or

if you reduced frenzied moments significantly? Bathe in the dream or memory of calm; let it inspire you to find more of it.

Take care of your mind and body

The quickest path to lowering frenzy is to move your body: go for a walk, go to the gym, take a yoga class or, if you don't have time, do a vigorous physical activity for a short period. Even five minutes of stretching, skipping down a hallway, climbing a few flights of stairs or doing a dozen lunges or squats can reduce the frenzy rapidly.

Feeding your body frenzy-reducing foods also works quickly. Eating enough protein, hydrating with water, savoring a bowl of berries or cutting down on coffee, sugar, processed or deep-fried foods will stabilize your blood sugar and feed your brain with a frenzy-controlling diet.

A few moments of meditation, listening to a favorite song or talking to a favorite friend can also quickly settle a frenzied brain. At the end of the day, celebrating with a walk or glass of wine (just one!) can wash away the day's frenzy. This isn't a book on optimal sleep or stress management per se, but both are critical for reducing frenzy and may be strategies to consider.

Physical sensations of frenzy can be caused by internal inflammation caused by gut allergies to wheat, dairy or other foods. Those who have gluten sensitivity (like me) find that eating something with even a small amount of wheat brings agitation and grumpiness.

Focusing first on developing healthier habits will lower your baseline frenzy, allowing you to more easily address other sources of stress.

Dig up and deal with longstanding sources of internal emotional frenzy

If you start to discover that you've got a level of frenzy that seems out of proportion, illogical or unfounded relative to your external or internal world today, perhaps you have some hidden, hard-to-get-at emotional

wounds and patterns that have escaped or overwhelmed your brain's built-in ability to heal. The understanding and reasons for why you feel what you feel may seem out of reach. There are many varieties of therapy available to help you access, understand, appreciate, process, heal and let go of these emotional wounds if you're open to seeking help and figuring out which approach will work best for you.

Perhaps your level of panic or anxiety has biological originsâyour brain chemistry is predisposed to overreact or react inappropriately. Talk to your physician to determine whether there is a medication that will help, even in the short term as you work on long-term solutions.

Plan life decisions that will remove big sources of external frenzy

You may have chosen a life path that is increasing your frenzy: the wrong career, the wrong job, the wrong marriage or the wrong social network. These are not easy areas to address, but even deciding that you will address them by proactively taking one small step at a time will provide hope that the life stages will eventually improve or pass.

On the other hand, life stages and events may choose you: problems in a relationship, a bad boss, health issues or the unavoidable process of aging. You may not be able to remove the stressful life situation and so then need to focus on getting stronger and managing the negative emotions a little better, day by day.

Learn that your response to frenzy is a choice, and make a choice to lift the frenzy

The bottom line is that you are in charge, and you have a choice. You can choose to work on being calm more and frenzied less. You can choose to get help. You can choose to bounce back when you have a bad moment, bad day, bad week or even a bad year. You can choose to learn, to grow

and to overcome. Calm, not frenzy, is your birthright. It's a treasure that you already have, waiting to be discovered.

Stoke up the motivational fires: make sure you're not

benefiting

from the frenzy

If you're reading this book, it's unlikely that you are in denial about the fact that you have too little calm and too much frenzy. However, even if you are aware and accepting of this situation and keen on reducing your frenzy, it's important to remember that some stress and some frenzy in our lives is normal and may even be beneficial.

It could be argued that without stress there would be no achievements, no productivity, no challenges in our lives. Except for perhaps that week in the Caribbean, getting the daily or weekly stress graph down to 0 is not only unrealistic but unhealthy. Think about all of the good things that you get out of stressâthe good job, the wonderful home, and the full and balanced life you've structured for your children. That didn't happen without stress and frenzy. Smile and appreciate how stress serves you. Next time it arrives, embrace stress for its benefits, and let go of excess frenzy, which makes you feel like you're driving with the brakes on.

Experiment

Now you are self-aware of what makes you calm and what detonates frenzy, you are yearning for more moments of calm, you've defined your ideal calm state and you're feeling empowered to get into the driver's seat. You're leaving the driveway, and learning how to drive and how to navigate the road to more calm. Change is not a straight line to the finish; it's a winding roadâsome steps forward and some, and hopefully fewer, backward steps. So abandon the perfectionist voices and enjoy being a scientist who loves to experiment. Develop some ideas about

how you might elicit calm from the frenzy in any given moment. Test them out and see what works best.

Look at a photo that makes you smile. Take a few deep breaths. Think of something that makes you grateful. Send someone an unsolicited note of appreciation for what she brings to your life. Read a comic strip. Go outside and breathe in some fresh air. Do a yoga pose. Water a few plants. Text your wife and tell her that you love her. Take the dog for a short walk. Remember a pleasant memory. Get a colleague a coffee. The possibilities are endless.

Build skills, success and confidence in taming frenzy

Once you've found some strategies for eliciting calm and taming your frenzy that deliver early motivation-enhancing gains, work diligently over a few weeks on becoming skillful and wiring them as new habits. Practice and practice until the strategies become automatic and effortless, until you get to the stage where you can't imagine not actively eliciting calm in a skillful manner when the frenzy bomb goes off. As you get more skillful, you'll get more successful and your confidence will grow like an upward spiral. You'll have more calm moments, which will be very pleasant, even surprising in their impact, and will reignite your motivation to keep going.

You're in control, at least most of the time!

Just as you've become aware of when you're calm and when you're frenzied, stop and notice even the smallest of improvements as you work on having more calm moments and fewer frenzied moments. Score them on a scale between 1 (total frenzy) to 10 (extreme calm), and even if you go from a score of 5 to 6, be sure to pat yourself on the back and feel gratitude for the progress. Share the progress and encourage and help others to set out on this same journey. Calm feels good and is infectious. Spread the word!

Rules of Order/

Sustain Attention

P

AY ATTENTION, GET FOCUSED,

be vigilant, stay on task, keep your eye on the ball, listen up, get your head in the game: these are just a few of the many ways we have of calling on that very basic human skill of paying attention.

There may be good reason for the variety of ways in which we ask each other to pay attention. In these fast-paced times, our attentional abilities are highly taxed. The world is demanding our attention at every turn and around every corner.

The ability to sustain focus is one of the building blocks of organization. It is step

two

in our process to help you become more organized. The first step is to establish emotional controlâto “tame the frenzy.” Now we are ready to take the next stepâto sustain attention and to stay focused for greater lengths of time.

Of course, asking people to pay attention is simple. But from a brain science perspective, the actual process of doing so is a remarkably involved task, requiring work from many distinct brain areas. Paying

attention is far more complex than, for example, the act of looking at something or someone. Indeed, there are neuroscientists who devote lifetimes to the study of attention. Obviously we can't go into that kind of depth here, but because the ability to pay attention is such a critical component of personal organization, it's important that we understand something about how it worksâparticularly as our understanding of it has evolved and changed in the past few years.

The first step in what we call the “attentional process” is to orient to the stimulus, whether it's the commercial on television, the teacher at the head of the classroom, or the red light flashing in the distance. Actually, let's imagine that light flashing in the distance is the signal from a fire engine, racing down the street. You turn and look in the direction of that sound, as your brain locks in on it. Think about just that for a moment. Consider how quickly we stop, look, listen; how fast our reaction time is; and how, in the blink of an eye, we have identified what the vehicle is, what direction it's coming from, and its probable purpose. Let's add the whiff of smoke in the air, and you've deduced even further what is happening and where that fire engine is going. In doing all that you have still used three of your sensory modalitiesâauditory (hearing), visual (seeing) and olfactory (smelling). Your tactile (touching) and gustatory (tasting) senses will have to wait until dinner.

Next step in the attention process is our engagement with that information as the fire engine comes blasting by. First simple orientation to the noise, now lots of attention to detail. You notice it festooned with ladders and tanks, an impressive complement of modern firefighting equipment. You see the firefighters in their gear; you catch a fleeting glimpse of determined faces under their helmets. You read the lettering on the side of the truck and see which firehouse the engine has been dispatched from and recall that you've passed

that building. Perhaps you even recall an episode from the television show

Rescue Me,

a scene from the day your child's class visited the local firehouse or something you read in the local paper about the fire department requesting funds for new equipment. You are now attending to this “stimulus” fully, pulling in and synthesizing bits of information from various parts of the brain. You are homing in on the sound and bringing to it the full and awesome powers of sustained, focused attention. And yet it's all happening in a matter of seconds. Take a moment to acknowledge that innate human skillâand to congratulate yourself on your facility for being able to attend to a great deal of information so quickly! Remember also that no matter how disorganized you may feel or how inattentive you may have been on the job or at home lately, chances are that if a fire engine really did come barreling down the street right now, you'd be able to attend to it with the same richness and breadth of cognitive resources we have described.

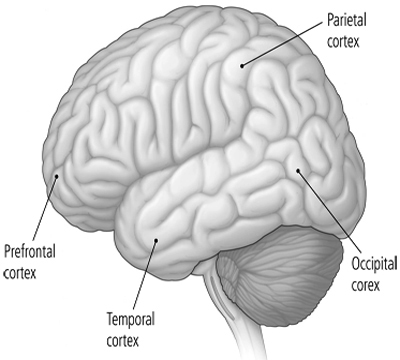

Let's talk a little about how you are able to do that and about important areas of the brain “cortex,” the area we must pay attention to when discussing this.

Cortex

comes from the Latin word for

bark.

It is the coating of the brain surface, those folds/crevices we mentioned earlierâand much of the information processing for the brain happens there. There are several specialized cortical areas, serving different functions.

One way of describing the brain's attentional workings is to begin at the back (posterior) of the brain cortex and move forward, somewhat akin to the way the fire-engine sound began in the background, in the distance, and then became clearer, as the truck raced toward you. Similarly, sensory information taken in by your eyes is received in the back of the brain (occipital cortex) and moves forward in the temporal and parietal cortices.

Source: National Institute of Drug Abuse Teaching Slides

The parietal cortex is involved in scanning the environment around you, analyzing motion, considering spatial relations and orienting you in time and space. It is key in that first orienting step, in which you focus on new stimuli. The temporal cortex is also involved in attending to the features of stimuli. While the parietal cortex gives us the heads-up to direct our attention that something is coming, the temporal cortex allows you to identify more about what that something isâits color, shape, sound and other features. You focus on a particular detail, like the pitch and volume of the siren or other salient information, such as a bright, flashing red light.

All of this information is processed, refined and integrated with memories of relevant prior experiences as the nerve cell messages move forward through your brain, taking information to the “control nodes” of attention in the front of the brain, the prefrontal cortex (PFC)âthe area responsible for our actions and responses to this information. The

PFC is considered a “control node” for attentional processesâa critical gatekeeper of attention. This should not be surprising, considering its key role in the management of emotion, as we discussed in the previous chapter. Its function is to help us sustain attention over longer periods of time, as we continue to receive and consider information coming in to us (and plan to start actually doing something about it). The PFC helps us to block out irrelevant stimuliâthe cell-phone conversation going on next to you when you first noticed the fire engine or the people walking across the street. While attention begins with orientation and continues with sustained focus, it also depends on our ability to handle distractions that could disrupt us along the way. As we will discuss in the upcoming chapters, the PFC is involved in more complex aspects of attention and organizationâincluding the ability to shift attention from one thing to another and to use memory to keep attention on something, even when it's out of sight.

Of course, in the case of the fire engine, what we have just described is the process and the mechanisms of attention working perfectly, the PFC and other parts of the brain fully engaged and the stimulus powerful and striking.

That's not always the case.

CASE STUDY: THE LIMITS OF ATTENTION

Nancy was in her thirties, a certified financial planner and an up-and-coming star with a local financial firm. But she had a problem.

“I can't seem to get things done. I can't focus on anything. I'm scattered. I'm all over the place,” she said, as she sat in my office.

But she had a good job and told me that she's recently been promoted. Surely, she must be doing something right, no? “Yeah,

they're happy with me at this firm,” she admitted. “But the more responsibility I'm given, the more I'm struggling to keep up. I'm afraid I'm going to blow it.”

Because your environment and changes in your environment can affect your ability to sustain attention, I probed her about her job and her workplace. She told me that in addition to her time on the computer or on the phone with customers, her office door was always open, and people were often dropping in with questions. She's also frequently summoned into meetings. Clearly, she's in a busy, potentially distracting situation. Also, it appears as if the level of work, and hence the level of attention and focus required of her, has grown. It could very well be that she's reached her limits.

“Is this something you've noticed for a long timeâ¦these problems you're having with focus?”

“Not really,” she said, although there have been times, here and there. “In my last job,” she said, “I was put in charge of this special project. I suddenly had all this extra responsibility and got so overwhelmedâ¦,” she stops and giggles. “One time, I was supposed to show up at a meeting at 5:00 pm, I totally got distracted and went out for drinks and dinner with a friend instead.” She looked at me and smiled. “At least it was a good dinner!”

The majority of patients who walk into my office have a clear lifelong pattern of persistent, problematic symptoms of ADHD. The rest are somewhere along the spectrum from “healthy” to ADHD; with symptoms of inattention and disorganization, to varying degrees, for limited periods of times, a diagnosis of ADHD is not made. Nancy doesn't seem to have ongoing, lifelong problems with attention but, rather, sporadic ones at various times in her life. It appears that now is one of those times.

“Do you feel like you've hit your capacity?” I asked her. She furrowed her brow. “My capacity?”

“Yup,” I said. “Sounds like this is a time in your life when “you have reached a certain point, when there is more asked of you, more information for you to focus on, more distractionsâ¦like you have reached your attentional limit.”

“That's interesting,” she said. “I didn't know that your ability to pay attention even had a limit.”

A FINITE RESOURCE

Despite all of the brain's impressive attention hardware, there is indeed a limit to what it can deal with and for what duration. How long is a “normal” attention span? The “healthy” adult population can feel confident that their focus can be maintained for upward of an hourâabout four times as long as the ten to fifteen minutes people with ADHD often cite as their typical attention span. That is, unless there is an impending deadline, significant pressure from a boss or a spouse or a task that is particularly novel or interesting. In those situations people with ADHD can focus for longer periods of time. But typically, for people with ADHD, instead of focusing on the task at hand, within minutes they are out of their seats, getting a drink of water, looking out the window or surfing the web.

Their basic unit of attention is very brief and has always been very brief, since early childhood.

What affects this length of time? Many factors. Not surprisingly, we tend to pay closer attention to that which is interesting or perceived as relevant and important to our goals or when there are some particularly striking factors related to it. So the meeting with the financial planner about your nest egg; the fast-paced, page-turning novel by the author you love; or the fire engine with the siren screaming, horn blaring and

lights flashing are all more likely to be winners in the ongoing battle for your attention. These things are “salient.”

Some people's abilities to block out extraneous stimuli and concentrate are legendary: It was said that Ulysses Grant, the famous Civil War general (and later president) had an almost “superhuman” ability to stay focused, even in the din of battle. Cannons roared, smoke filled the air, chaos reigned, and Grant was still able to focus fully on reports from the field and make key decisions. Historian and author Mark Perry called this the general's “most sterling quality. While not the tallest, or strongest, or brightest or even the most insightful of men or generals, Grant brought a singular concentration to everything he did.” Grant's remarkable attention powers paid off at the end of his life. Racing against a case of terminal throat cancer, he attempted to finish his memoir in order to obtain for his wife and children the profits of his book, which would resuscitate his family's financial situation. Despite great physical pain and discomfort, he paid full attention to the writing and revisions of the book. He finished on July 19, 1885âand died four days later. Now

that's

focus. A year later, his widow received a check for royalties totaling $200,000.

On the flip side, we have someone like Nancy. Normally, she was probably able to pay attention to her work for thirty or sixty minutes or even more. But when the workload increased suddenly and she was being forced to process and deal with greater amounts of information, the “wheels” of attentional progress screeched to a halt.

Sometimes, if we are not fully allocating and using our attentional capacities (as we might with the fire engine, the good book or the important financial meeting), then the information might as well not be there at all. Perhaps you've had the experience of a colleague saying, “I sent you that memo the other day; don't you remember?” or your spouse insisting that “I showed you where the spare key was; you

must have forgotten.” You're dumbfounded because you honestly

don't

remember ever seeing the memo or the key. It's as if these things never happened. What

did

happen is that we

didn't

pay attention; we weren't processing that information when we were told or when the memo or key was shown to us. The act of paying attention is not always an automatic process. Without our concerted efforts to do so, events, information and experiences can pass us by. It's intriguing to think that “I can't remember” may really mean “I wasn't paying attention in the first place.”