Pompeii (28 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

The decoration of Pompeian houses has kept scholars busy for centuries, figuring out the chronology, the aesthetic and functional choices made, the meaning of the myths on the walls. Fascinating details continue to be discovered on everything from the logic of the designs to the technical procedures of the painters who carried them out (the House of the Painters at Work only began to be unearthed in the late 1980s, and the excavations are still incomplete). But there is an important and obvious point about the domestic style of this Roman town which often gets lost among the detail.

To judge from their plans and the surviving remains, many if not most Pompeian houses would count as claustrophobic places. Only a few of the very richest exploited any kind of view onto the outside world; the vast majority were inward-looking, with hardly more than a couple of tiny windows, to bring in light, onto the street outside. Most of the rooms were small and dark. And although some (the wealthiest again) were endowed with lofty atria and with extensive internal gardens and walkways, in many even the atrium must have felt relatively cramped (especially when filled with all those cupboards and looms) and the garden was not much more than pocket-handkerchief size, more a light-well than a place of pleasure and relaxation.

Yet the painted decoration tells another story. The clever tricks of illusion suggest vistas that do extend beyond the confines of the house. In the most extravagant cases the internal walls seem to dissolve into a vision of competing perspectives, glimpses beyond the horizon and distant views. Around the borders of the tiny gardens, it must sometimes have been hard to decide at a glance where the domestic plants stopped and the wild landscapes or the river Nile started. Even in the more austere First Style, the viewer is confronted with the puzzle of what the wall they are looking at really consists in: is it painted plaster and stucco or the marble blocks that it pretends to be?

This sense of something beyond the house is powerfully reinforced by the subjects of the wall paintings. Pompeii was, after all, a small town in southern Italy. Yet it is striking how far its cultural and visual reference points extend: across the Mediterranean, through the repertoire of ancient literature and art, to more exotic shores beyond. The imaginary world of decoration was not claustrophobic in the slightest. It embraced a galaxy of Greco-Roman myth and literature, from the Homeric epics on; it evoked and adapted the masterpieces of classical Greek painting; it exploited the cultural highlights of Egypt, from sphinxes and the goddess Isis, to satires and burlesques on its inhabitants and their weird customs. This is not, of course, all benign multiculturalism. The stereotyped pygmies chasing crocodiles or having riotous sex are portrayed with a mixture of aggressive humour and xenophobia. But the crucial fact is that these distant horizons were portrayed at all. On top of its mixed cultural roots in southern Italy, Pompeii was part of the global Roman empire – and it shows.

It shows also in the other forms of ornament and bric-a-brac that have been found in these houses. The Indian statuette of Lakshmi (Ill. 11) may be an extreme and unusual case of cultural ‘reach’. But there is plenty of other material to suggest how outward-looking the world of the Pompeian house could be, at least for those with enough cash to spare for decoration. There are, for example, columns, floor tiles and tabletops made from expensive coloured marbles, imported from far-off parts of the empire – from the Peloponnese and the Greek islands, from Egypt, Numidia and Tunisia in Africa, from the coastlands of modern Turkey. Overall Greece, and its history, was in the forefront: a rough-and-ready terracotta statuette identified on its base as ‘Pittacus of Mytilene’ (a sixth-century BCE Greek sage and moralist) and found in the Estate of Julia Felix; an elegant mosaic with a group of Greek philosophers chatting under a tree with what looks like the Athenian Acropolis in the background, unearthed in a villa just outside the city; and of course the Alexander mosaic.

One of the most striking discoveries is from the House of Julius Polybius. Packed away with other valuables at the time of the eruption, in the grand room with the painting of Dirce, was a fifth-century BCE Greek bronze jug. It had originally been, as an inscription on it declares, part of the prizes at the games held in honour of the goddess Hera at Argos, in the Peloponnese. After a chequered career in which it lost its handles (one suggestion is that it was used in a burial) and had a tap added, it ended up in Pompeii. Whether a prize purchase or a family heirloom, it was a nice reminder of a world and a history outside Pompeii.

How the painters in the House of the Painters at Work had intended to fill the large, as yet blank, panels we shall never know. Nor can we know if they took to their heels in time to escape to safety. But there’s little doubt that their job had been to create, in paint, ‘a room with a view’.

Plate 1. Mosaic of musicians, probably intended to depict a scene from a comedy by the fourthcentury Greek dramatist, Menander (pp. 253–4). It comes from the so called Villa of Cicero, just outside the Herculaneum Gate.

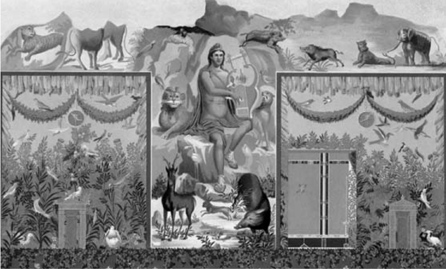

Plate 2. The whole of the garden wall of one house carried this striking scene of Orpheus charming the animals with his music (p. 128).

Plate 3. Is this the emperor Nero? This painting from a luxurious dining room in a building just outside Pompeii has been identified as Nero in the guise of the god Apollo. So, it has been suggested, this may have been where he stayed on his visit to Pompeii – if he really did visit Pompeii, that is (p. 50).

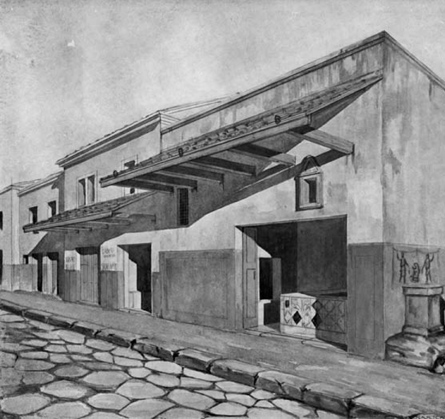

Plate 4. Reconstruction of a typically colourful façade on the Via dell’Abbondanza. On the far right a crossroads shrine, then an open bar or shop counter. Election notices are painted on the next door house. Above, wooden overhangs shade the street and entrance ways.

Plate 5. The carpenters display their craft in a procession. At the far left was a statue of their patron deity Minerva, though little more than her distinctive shield survives. In the middle is a model of their carpentry work (pp. 294–5).

Plate 6. The gaming table, from a painting in the Bar on the Via di Mercurio (p. 230–31). The brightly coloured, casual clothing contrasts with our image of white toga-clad Romans.

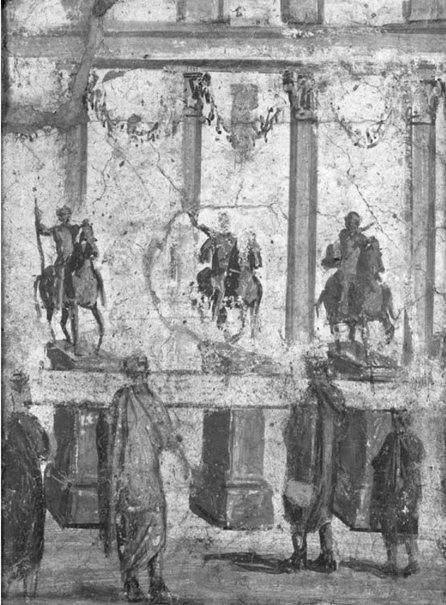

Plate 7. One of the best preserved of the scenes of Forum life from the Estate of Julia Felix. A group of men consult a written notice that has been displayed across the bases of the statues in front of the colonnade (p. 76).