Pompeii (32 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

There was plenty of trade in the other direction too. If Pompeii could in theory have supplied its needs entirely from the surrounding territory, it certainly did not choose to do so – or, at least, not by its later years. The pottery jars for wine and other foodstuffs tell a clear story of imports on a relatively large scale. Many of these came from not so distant parts of Italy. Richer Pompeians, for example, enjoyed Falernian wine, one of the classiest

premier crus

of the Roman world, produced some 80 kilometres to the north of the city. But there were imports from further afield too. In the House of the Menander some seventy

amphorae

and other jars were discovered, many still bearing indications of their contents and place of origin. True, there were some very local products: a couple bore Eumachius’ stamp, another couple had contained wine from Surrentum and one, much smaller, local honey. But some had brought olive oil or fish sauce from Spain, others were from Crete, and at least one came from Rhodes and was billed as containing

passum

, a special variety of sweet wine made out of raisins, rather than fresh grapes. Roughly the same picture emerges from the store of

amphorae

, some full, some empty, in the run-down House of Amarantus. Probably a mixture of first-, second-, or third-hand containers, they included a substantial number that had originated in Crete (thirty, apparently full, which must have been a recent shipment), a couple from Greece, and one – a rare specimen – from the city of Gaza which, in a poignant contrast to its present state, was to become one of the most celebrated and profitable centres of wine production in the early Middle Ages.

The import business dealt in more than the contents of

amphorae

and other jars, whether wine, olive oil or

garum

. We have seen how microscopic analysis has brought to light the remains of exotic herbs and spices (see p. 37). But other sorts of relatively indestructible materials, such as fancy Egyptian glassware and coloured marble, are even easier to trace. Ordinary ceramic tableware could also come from well outside the local area. In fact, one packing case containing some ninety new Gallic bowls and almost forty pottery lamps was found intact, presumably having arrived in the town too close to the eruption ever to have been unpacked. In this case, if archaeologists are right to say that the lamps were made not in Gaul, but in northern Italy, we must imagine that some kind of ‘middleman’ had been involved, packaging up a mixed consignment.

All in all, there can hardly be any doubt that, wherever exactly it was, and however small by comparison with the great trading centres of Puteoli or Rome, Pompeii’s port must have been a thriving, international and multilingual little place.

City trades

Agriculture was not only an activity for the countryside outside the city. Current estimates are that within the city walls as much as 10 per cent of the land, even in the years leading up to the eruption, was in agricultural use; in earlier periods it would have been even more. Some of this was the home to animals, an underestimated part of the Pompeian population, largely because earlier generations of archaeologists tended to overlook animal bones. But even they did not miss the skeletons of two cows which were in the House of the Faun when the eruption came, and we shall be looking at another yet more dramatic discovery later in this chapter. There was plenty of cultivation too. We have already glimpsed a small ‘kitchen garden’ in the House of Julius Polybius, with a fig tree, and olive, lemon and other fruit trees. There were other cases of city cultivation on a much larger, more commercial scale.

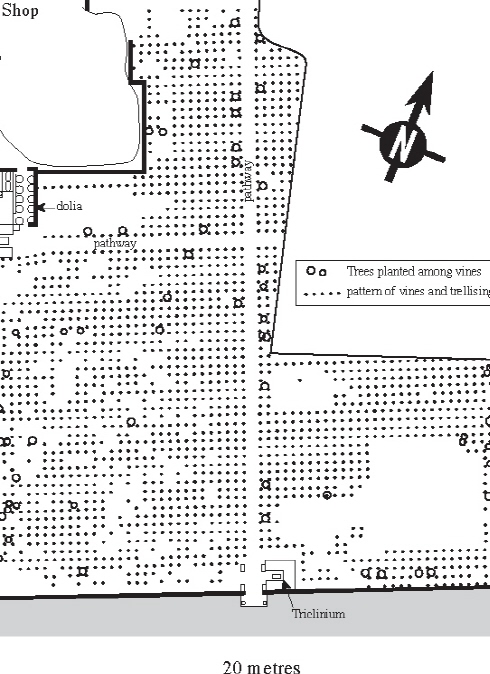

On one piece of open ground near the Amphitheatre, once thought to be the burial ground for dead gladiators, or alternatively a cattle market, careful excavations in the 1960s revealed a closely planted vineyard (Fig. 13), with olive and other trees growing among the vines, and possibly vegetables too (or so it has been deduced from the discovery of a single carbonised bean). The vineyard covered about half a hectare, and the wine – several thousand litres of it – was not only produced on the spot (as the wine press and large

dolia

show), but was also retailed from a bar facing onto the Via dell’Abbondanza or served to customers dining at one of the two outdoor

triclinia

built at the edge of the property. And there were many other, smaller vineyards, orchards and vegetable gardens (stocked with those famous cabbages and onions, perhaps), all identified from the traces of root cavities, carbonised seeds, pollen and carefully laid-out beds and irrigation systems. In one garden, with a particularly elaborate watering arrangement, it seems as if flowers were being grown commercially – maybe, it has been argued from the quantity of glass jars and phials in the adjacent house, for the production of perfume. Some very recent work has found evidence of ‘nurseries’ which probably supplied the local gardeners with their herbaceous plants.

Figure 13

. Plan of an excavated vineyard. Painstaking modern excavation has revealed the planting of this commercial vineyard (plus dining establishments) within the walls of the town. It was well positioned for different types of trade. On the north it faced onto the Via dell’Abbondanza; to the south, it would have been convenient for customers from the Amphitheatre.

It should be no surprise, then, that so many pieces of agricultural equipment have been found in the city’s houses: forks, hoes, spades, rakes and so on. Some of these were no doubt used by those who lived in the town but went out, day by day, to work on fields outside the walls. But others would have been for use on city-centre plots of land.

The overall impression, however, of a walk through Pompeii was not of a world of peaceful gardening or other pastoral pursuits. This was a bustling, commercial, market town. True, land and agriculture almost certainly remained the most significant basis of wealth throughout the city’s history. Pompeii was not, as some modern fantasies have suggested, an ancient equivalent of Renaissance Florence, where economic success was built on manufacturing industries and political power was vested in the guilds which controlled those industries and in the financial wheeler-dealers who invested in them. The fullers and textile workers of ancient Pompeii were no driving force of economic power. The ‘banker’ Lucius Caecilius Jucundus, whose business we shall shortly be exploring, was no Cosimo de’ Medici. That said, Pompeii provided a whole range of services, from laundry to lamp-making, and acted as a centre of exchange for a community of probably more than 30,000 people, country dwellers included.

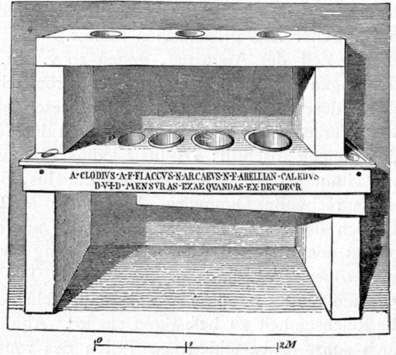

This meant an infrastructure for buying and selling. The local council took care to regulate the standard of weights and measures used by traders. The official gauge had already been set up in the Forum in the second century BCE, following Oscan standards of measurement (Ill. 60). These standards were adjusted, as an inscription on it declares, at the end of the first century, to bring it into line with the Roman system – a change which, whatever the council’s rulings, may have been as patchy, contested and politically loaded as the British change at the end of the last century from imperial measures (pounds and ounces) to metric (kilos and grams).

But the involvement of local government in the commercial life of the city went further than this. We have already seen the aediles assigning sales pitches to traders (p. 71). They may also have regulated the dates of markets. A very messy graffito on the outside of a large shop (‘Lees of

garum

for sale, by the jar’) lists a seven-day cycle of markets, based on days of the week much like our own: ‘Saturn’s day at Pompeii and Nuceria, Sun’s day at Atella and Nola, Moon’s day at Cumae ... etc.’ This may reflect an official and regular commercial calendar, rather than just a one-off, one-week timetable. That, at least, is what most archaeologists have assumed, glossing over the fact that another graffito appears to put Cumae’s market day on Sun’s day and Pompeii’s on Mercury’s day. Either way, this seems evidence for some degree of official planning and attempted coordination.

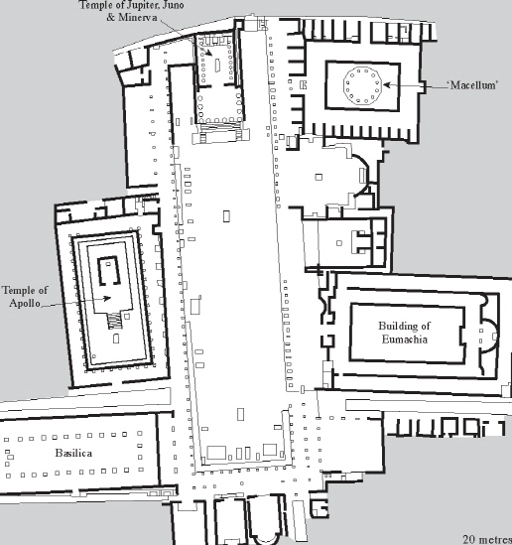

It is likely too that the local council had control over the city’s major communal, commercial buildings. These have been harder to identify than you might imagine. In fact, the question of what many of the large buildings that surrounded the Forum were actually used for is, despite many confident claims, one of the biggest puzzles of Pompeian archaeology. According to the currently favoured guesses, the long narrow building in the north-west corner of the Forum (half of which is modern reconstruction after the Allied

Blitzkrieg

) is some kind of market, perhaps for cereals. Opposite, at the north-east corner, stood the meat and fish market. For the first of these identifications there is no evidence whatsoever, apart from the fact that the official weight gauge is nearby. The second may be correct. But it depends on taking very seriously the fish scales found in the central area and playing down the possibly religious elements and the painted decoration which seems rather too elegant for a market (Ill. 61). Some archaeologists have preferred to see it as a shrine or temple – or (in the case of William Gell) a shrine-cum-restaurant.

60. Cheats beware. An official gauge of measurements was established in the Forum. Originally it followed the old Oscan standard, but as the inscription on it declares, it was adjusted to conform to Roman standards in the first century BCE.

Whatever the official involvement in local commerce, particularly striking is the sheer variety of trades and businesses carried on in the town. Today, just wandering through the streets, it is easy to spot the sturdy stone mills and the large bread ovens used by the bakers, or the vats and troughs used by the fullers in their textile processing. Meanwhile the cabinets of the Naples Museum are full of the tools and instruments of all kinds of crafts found in the excavation: from heavy-duty hatchets and saws, through scales to balances, plumb-bobs and pliers, to fine-tuned doctors’ equipment (some of it, like the gynaecological

speculum

(Ill. 7), uncannily modern).

Figure 14

. Plan of the Forum. The civic centre of Pompeii, but to this day the title and function of many buildings around the Forum remain unclear.

These can sometimes be neatly matched up with surviving trade or shop signs. One rough-and-ready plaque, for example, once attached to the outside of a workshop, seems to advertise the skills of ‘Diogenes the builder’ with images of his tools (plumb-bob, trowel, chisel, mallet), plus a phallus thrown in for good luck. They even occasionally turn up on tombstones, celebrating the dead man’s craft. One Nicostratus Popidius, a surveyor, blazoned his instruments – measuring rods, stakes and the distinctive

groma

, or cross, used for laying out straight lines – on the memorial he commissioned for himself, his partner and their children. He had made his livelihood in one of the most characteristic of Roman professions, laying out plots of land, establishing boundaries between properties, advising on land disputes. This is just the kind of man who would have been in demand when Vespasian’s agent Titus Suedius Clemens turned up in the town to investigate the problem of the state-owned land that had been illegally occupied by private owners.