Pompeii (30 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

Plate 19. The garden wall of the House of the Ancient Hunt, named after this painting.

Plate 20. A nineteenth-century version of a miniature frieze in the House of the Vettii, showing cupids as metal workers.

Plate 21. Here, in the original paintwork from the House of the Vettii, the cupids have a chariot crash. (p. 126).

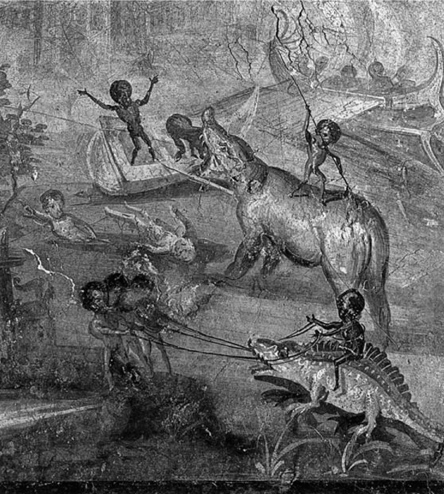

Plate 22. A vista onto a foreign world. In this painting, pygmies get into all kinds of adventures. One is riding a crocodile, another is apparently being eaten by a hippo, though help is at hand.

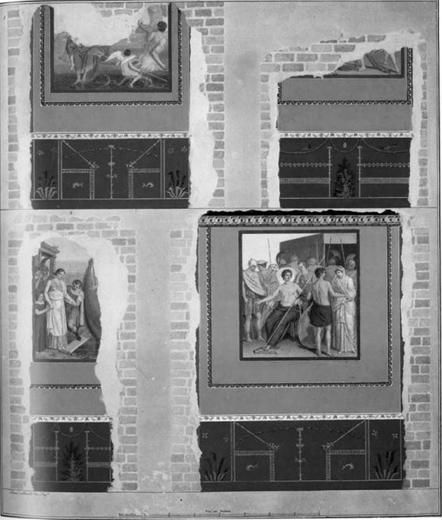

Plate 23. A composite image of the walls of the House of the Tragic Poet. On the lower left Helen departs on her journey to Troy. On the right, in another moment from the Trojan War, the prisoner Briseis is taken from Achilles to be given to Agamemnon (pp. 147–8).

Profit margins

Just along the street from the House of Fabius Rufus, in that row of grand mansions with views over the sea, stood a house occupied in the last years of the city by Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, a man who had made his money in the fish sauce (

garum

) business. He was, in fact, the biggest

garum

dealer in town. To judge from the painted labels on

garum

jars found in the area, he and his associates and subsidiaries controlled almost a third of the local supply of this staple of Roman food preparation. The house itself is a vast sprawling affair, made by knocking together at least two earlier, separate properties. It is now in a sadly dilapidated state, partly as the result of the bombing in 1943, which hit this part of town very badly. But in its final form it clearly had not just two, but three atria, as well as one or more peristyles (one with an ornamental fishpond), plus a bath suite on a lower floor.

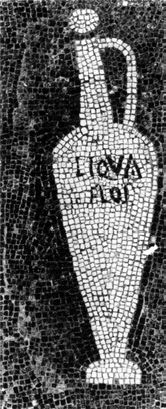

We know that it was owned by Umbricius Scaurus because the mosaic decoration on the floor of the third atrium once featured at each of its four corners a jar for fish sauce (Ill. 57). Now removed for safe-keeping, these were made out of white

tesserae

on a black background, and each one carried an inscription referring to different varieties of fish sauce sold by Umbricius Scaurus: ‘Scaurus’ best

garum

, mackerel-based, from Scaurus’ manufactory’, ‘Best fish sauce’, ‘Scaurus’ best

garum

, mackerel-based’, ‘Fish sauce, grade one, from Scaurus’ manufactory’. Unless we are to imagine that some satisfied customer chose to decorate his atrium floor with versions of his favourite sauce jars, then this must be the house of Scaurus himself. Here interior decoration was a form of self-advertisement and product promotion.

57. In the atrium of the House of Umbricius Scaurus, four jars of fish sauce in mosaic proclaim the family’s source of wealth. Here the jar proclaims ‘Best fish sauce’ – in Latin ‘

Liqua(minis) flos

’, literally ‘Flower of

liquamen

’.

Liquamen

was a variety of the (to us) better known

garum

.

Umbricius Scaurus was not the only resident of Pompeii explicitly to celebrate his business success on the floor of his house. At one of the main street entrances of another huge property, the visitor was greeted by a slogan picked out in mosaic: ‘Welcome, profit!’ The sheer size of this house is enough to suggest that the wish had been amply fulfilled. But elsewhere such words must have been more an expression of vain hope. On the atrium floor of a tiny house, we can still see the catchphrase ‘Profit is pleasure’. There is little sign here that this went beyond wishful thinking.

The Roman economy

Historians have argued for generations about the economic life of the Roman empire, about its trades and industries, its financial institutions, credit systems and profit margins. On the one hand, are those who see the ancient economy in very modern terms. The Roman empire was effectively a vast single market. There were fortunes to be made from the demand for goods and services, which also drove up productivity and stimulated trade to levels never seen before. A favourite illustration of this comes – unlikely as it may seem – from deep in the Greenland ice-cap, where it is still possible to find the residue of the pollution from Roman metal-working, not equalled again until the Industrial Revolution. Underwater archaeology tells much the same story. Many more shipwrecks have been discovered at the bottom of the Mediterranean, from between the second century BCE and the second century CE, than from any period until the sixteenth century. This is not an indication of the poor quality of either boat-building or seamanship in the Roman period, but of the high volume of sea-borne traffic.

On the other hand, there are those who argue that Roman economic life was utterly different from our own, in fact decidedly ‘primitive’. Wealth combined with social prestige remained rooted in the land and the main aim of any community was to feed itself, not to exploit its resources for profit or investment. Long-distance transport of goods was risky by sea (witness all those shipwrecks) and prohibitively expensive by land. Trade was only a very thin icing on the economic cake, small-scale and not particularly respectable. Inscriptions on mosaic floors may celebrate healthy profit margins, but there are few Roman authors, elite class that they are, with a good word to say for trade or traders. By and large, trade was vulgar and traders untrustworthy. In fact, from the end of the third century BCE, the highest echelons of Roman society, senators and their sons, were expressly forbidden from owning ‘ocean-going ships’, defined as those that would hold 300

amphorae

or more.

Besides, Rome developed none of the financial institutions needed to support a sophisticated economy. There was limited ‘banking’, as we shall see, in Pompeii. It is not even clear if there were such things as credit notes, or if you wheeled around a load of coins in a wheelbarrow to make large purchases, such as houses. And, while Roman metal-working may have polluted Greenland, there is very little trace of the kind of technological innovation that went hand in hand with the eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution. The biggest invention of the Roman period was probably the water-mill, and that – so this side of the argument goes –is not saying very much. But why bother with new technologies, when you have vast quantities of slave power to stoke the fires, man the levers or turn the wheels?

Country life and country produce

Most historians now come down judiciously somewhere between these two extremes. And Pompeii itself has features of both the ‘primitive’ and the ‘modern’ model of the economy. It is almost certain that the basis of most wealth in the city was the land in the surrounding area, and that the families which owned the largest houses there would also have had other properties and substantial holdings in the region round about. ‘Pompeii’ as an economic and political unit would have consisted of the urban centre plus its hinterland. The area beyond the city itself probably covered some 200 square kilometres – or, at least, that is a good, if slightly generous, guess, since we have no hard evidence at all where the boundaries lay between what counted as Pompeian land and that of neighbouring towns. It has not been very thoroughly explored by archaeologists, most of their interest being concentrated on the town. In fact, locating villas, farmsteads and other rural settlements under several metres of volcanic debris has been chancy.

Altogether the remains of almost 150 properties have been discovered in the hinterland of the city, but our knowledge of what kind of establishments they were or who owned them is very hazy, for only rarely have they been systematically excavated. Some were certainly pleasure villas for the rich, even those from as far away as Rome: it was not only Cicero who had his ‘Pompeian place’. Some were working farms. Others were a combination of the two. Almost certainly there is a bias, in what we have discovered, towards more substantial remains, rather than the huts and sheds of the poorer peasant farmers. If, as some archaeologists have half suspected, there were the ancient equivalent of shanty towns or squatter settlements of poor labourers in the countryside outside the walls, we have found no trace of them.

There is one case where we can pin down a country property of a leading Pompeian family. In the 1990s, excavation at Scafati, a few kilometres east of Pompeii, turned up a family burial ground, with eight memorials to various Lucretii Valentes in the first century CE, most of the men carrying exactly the same name, Decimus Lucretius Valens. They ranged from tiny children, like the toddler who died when he was just two years old, to a distinguished young man, who had been buried elsewhere at public expense, but was given a memorial plaque here alongside the rest of his relations, where he was celebrated for sponsoring, together with his father, a gladiatorial show consisting of thirty-five pairs of fighters. That was about as generous as a Pompeian benefactor could be.